Last updated: January 22, 2026

Person

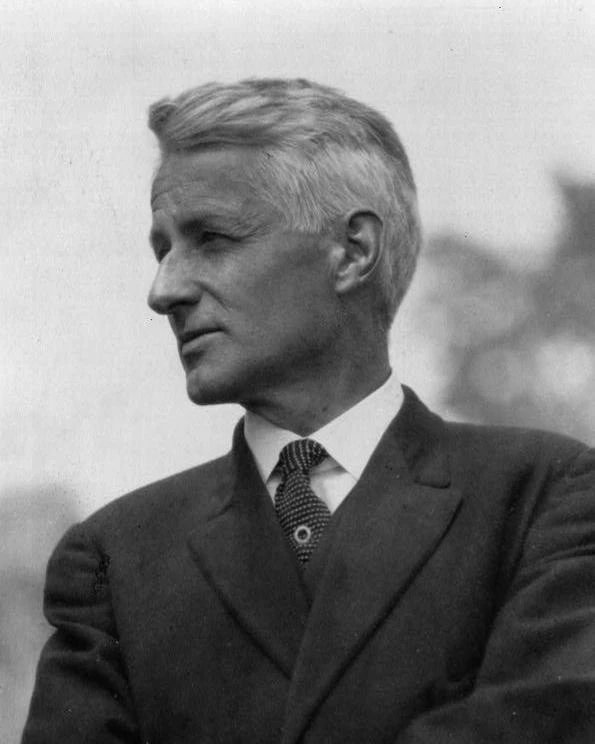

Maxfield Parrish

Library of Congress

Originally christened Frederick Parrish and known as Fred to close friends and family, he eventually adopted his middle name professionally and signed “Maxfield Parrish” to his characteristic illustrations of whimsical figures and sweeping landscapes. His style was so vibrant and distinct that one of his signature vivid hues has become known as “Parrish blue.”

After studying architecture at Haverford College and art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Maxfield Parrish joined his father in New Hampshire in 1898 and became an active member in the Cornish Art Colony. Parrish made the area his home for the next 68 years.

Parrish and Lydia Austin met in 1894, while she was working as an instructor of painting at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute; they married the following year. In 1898, the couple purchased a nineteen-acre lot in neighboring Plainfield on which they built “The Oaks,” a 15-room house whose focal point was a forty-foot-long music room that included a fireplace and stage for their favorite charades.

Appropriately, Parrish made full use of the natural setting, allowing several fine old oaks to determine the location of the house. Like his father, Stephen, Maxfield Parrish’s gardens were well known for their beauty. A rising voice in horticulture writing, Frances Duncan (a future Cornish Colony member), published an article in 1905 in The Ladies’ Home Journal emphasizing Parrish’s craftsmanship in designing the house and extending to the garden. She wrote, “…the site is, for Cornish, a thoroughly characteristic one – a rough sheep pasture which, seen from a distance, seems to rise up clear against the sky.” From the garden, “one looks down a valley wonderfully rich in that picturesqueness of landscape which is so integral a part of Mr. Parrish’s work.”

Dubbing himself “the mechanic who paints,” he built a studio just a few steps away equipped with woodturning machinery, a stove to help his layers of paint dry, and a darkroom. He would use his wood lathe to make many of the urns, vases, and furniture used in his painting, and even engineered a car that ran on tracks to bring wood up in an elevator and a trapdoor in the floor that allowed his many murals to be lowered into the garage. The house burned down in 1979, thirteen years after Parrish’s death.

The Parrishes were among the few Colony members who lived in Cornish all year. They entertained frequently, giving dinners, hosting recitals, and holding other social events for actress Ethel Barrymore, author Winston Churchill and his wife, Mabel, and President Woodrow Wilson and his family. When members of the Cornish Colony produced “A Masque of Ours: The Gods and the Golden Bowl” in 1905 to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Colony’s founding, Parrish played a prominent role. He designed and created the two gilded masks that held back the curtains, as well as his own costume, an elaborate contraption transforming him into a wise old centaur.

Parish’s career as an illustrator began with a cover for the magazine, Harper’s Weekly. Eventually, he received scores of commissions for his art from companies and organizations that brought him much commercial success. He illustrated many of the period’s most well-read children’s books along with advertisements, greeting cards, and calendars. His success was, in part, due to the rigid standards he set for himself. In 1904, renowned author Edith Wharton published Italian Villas and Their Gardens, lavishly illustrated by Parrish; the book fostered a growing interest in landscape architecture.

The Curtis Publishing Company commissioned Parrish to paint 18 large scale murals (each over ten feet high), with a carnival theme in 1905. Considered one of his most significant artistic feats, the job took him more than eight years. Sue Lewin, from Hartland, Vermont, was one of his primary models, working for him for over 50 years and appearing regularly in the paintings used for his many magazine covers and advertisements.

In 1916, the Plainfield Players (later known as the "Howard Hart Players") dedicated a new theater stage inside Plainfield, New Hampshire’s town hall that Parrish likely painted. The hanging backdrop, wings, and overhead drapes depict a forested landscape with Mount Ascutney in the distance. This cultural treasure continues to be the backdrop for community events and is preserved by the Maxfield Parrish Stage Set Committee of the Plainfield Historical Society.

Parrish received the gold headed Boston Post Cane from the Plainfield selectmen in 1963 (given to the town’s oldest citizen); he lived for three more years. Increasingly focused on his immediate surroundings toward the end of his career, Parrish painted largely local landscapes, saying, “…a man can’t step out of the subway and watch the clouds playing with the top of Mount Ascutney. It’s the unattainable that appeals.”