Last updated: June 2, 2021

Person

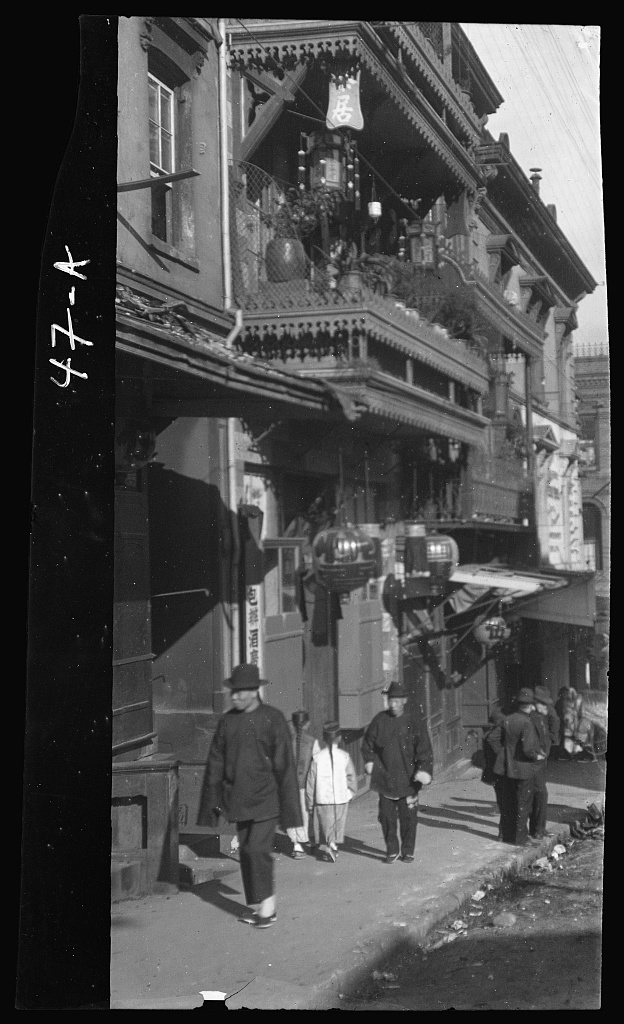

Mary Tape

Public domain.

Almost 70 years before Brown v. Board of Education, Mary Tape fought for her daughter’s right to attend public school in California. Mary immigrated to the United States from China when she was eleven years old. In 1884, she tried to enroll her eight-year-old daughter Mamie at a white public school in San Francisco.[1] When school authorities turned Mamie away because of her Chinese ancestry, Mary and her husband Joseph sued the Board of Education. The lawsuit became a landmark civil rights case for public school desegregation.

How do you know if you are not welcome somewhere? How would you feel?

Immigration and Family Life

Mary Tape was born in northern China near Shanghai in 1857. In 1868, at the age of eleven, she immigrated alone to the United States. Within five months of her arrival, San Francisco’s predominantly white Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society took her in. Established in 1853, this Society pledged to “render protection and relief to strangers, to sick and dependent women and children,” by helping them to find jobs and temporary housing. Under their care, Mary learned English and American culture. She adopted the name Mary McGladery after of one of her caretakers.

In the early 1870s, Mary married Jeu Dip. After Jeu Dip immigrated in 1864, he adopted the name Joseph Tape. He got a job as a domestic servant for a white family and later delivered milk from their dairy farm. Joseph met Mary on one of his deliveries to the Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society. Joseph eventually began his own delivery service for Chinese merchants from the docks to Chinatown. He later worked as a broker and interpreter for the Imperial Consulate of China.

Mary and Joseph Tape quickly learned that assimilating to American culture had social and economic benefits. They distanced themselves from the community in Chinatown. The Tapes began a middle-class  life together in Cow Hollow, San Francisco. They raised four children: Mamie, Frank, Emily, and Gertrude.

life together in Cow Hollow, San Francisco. They raised four children: Mamie, Frank, Emily, and Gertrude.

As the Tapes settled into their new lives, however, anti-Chinese discrimination was intensifying in the United States. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Act banned Chinese workers from immigrating to the United States. It also prevented them from becoming naturalized American citizens. These policies escalated the discrimination and exclusion Chinese immigrants faced. In California, Chinese immigrants endured racist stereotypes and even mob violence. They also faced legal restrictions on their civil rights to marry and testify against white Americans.

Chinese Exclusion and School Segregation

The anti-Chinese restrictions soon hit close to home for the Tape family. In 1884, Mary and Joseph tried to enroll their 8-year-old daughter Mamie at Spring Valley Primary School, an all-white school near their home. Although there were mission schools for Chinese children in San Francisco, those schools were farther away. The Tapes also knew that attending an all-white school would make it easier for their children to succeed.

Under a California state law passed in 1880, all children had the right to receive a public education. But members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors did not want Chinese and Chinese American children to go to school with white children. The Board maintained the racist belief that people of Chinese descent could not assimilate, which was one of the main arguments for Chinese exclusion. Yet they also supported segregated schools because they feared that education would help Chinese and Chinese American children to assimilate. Exclusionists believed that assimilation was the first step toward establishing a permanent, growing Chinese American population in the United States, which would defeat the purpose of the exclusion policies.

Before Mamie could set foot in the classroom, she was turned away because of her Chinese ancestry. Although she was born in the United States and was an American citizen, authorities at the school still viewed Mamie as a foreigner.

Anti-Chinese sentiment was common at the time. Many white Americans viewed Chinese immigrants as racially inferior and as competition for jobs. During the 1850s, California lawmakers and the courts singled out Chinese people as a separate race that was dangerous and untrustworthy. “Negroes, Indians, and Mongolians” were also excluded from public schools in California. Although Black, Native, and Asian American students could eventually attend segregated schools, access to an education remained inconsistent for several decades.

Mary Tape challenged Mamie’s exclusion from Spring Valley Primary School. She believed that it was wrong for her children to be segregated with other Chinese and Chinese American children because the Tapes were the “same as other Caucasians, except in features.” Mary argued that her family was just as American as their white neighbors, because they had assimilated to the standards of the white middle class. The Tape children spoke English, had American-style names, and wore American-style clothes. “My children don't dress like the other Chinese,” Mary Tape asserted. “They look just as phunny amongst them as the Chinese dress in Chinese look amongst you Caucasians.” Although the Tapes interpreted Chinese identity as cultural, the San Francisco Board of Education ultimately defined it by ancestry.

Tape v. Hurley

On Mamie’s behalf, Joseph Tape sued the San Francisco Board of Education; Andrew Jackson Moulder, the public-school superintendent; and Jennie Hurley, the principal of Spring Valley Primary School. On January 9, 1885, the Superior Court of California ruled that excluding “children of Chinese parents” from public schools violated state law and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because Chinese Americans supported public schools with their taxes, Chinese American children were entitled to a public education. When the defendants appealed the case, the California Supreme Court upheld the original decision.

Educators and administrators in San Francisco remained determined to keep Mamie from going to school with white children. As soon as the decision came down, Superintendent Moulder telegrammed the California legislature. State lawmakers quickly passed a law that established "separate schools for children of Mongolian or Chinese descent." The Board claimed that these schools provided a way for Chinese American children to receive a public education, albeit one that was segregated from white students.

Mary Tape refused to accept this result and declared she would never send her children to the segregated school. In the local newspaper, the Daily Alta California, she published her dissent:

It seems no matter how a Chinese may live and dress so long as you know they Chinese. Then they are hated as one. There is not any right or justice for them.

After the Verdict

Despite Mary Tape’s resistance, the Tape children did attend the segregated school. On April 13, 1885, Mamie and her brother Frank became the first students at the new Chinese Primary School in Chinatown. After several years, the Tapes moved to a more diverse neighborhood near the western part of Chinatown. Although they wanted to distance themselves from other people of Chinese descent, the Tapes also wanted to increase their children’s marriage prospects. They knew that interracial marriage was discouraged among both white and Chinese people.

Local newspapers had reported on Tape v. Hurley regularly and remained interested in the Tapes for years after the case. Although journalists only referred to Mamie as “that Chinese girl,” the press made the Tape family well known. Mary Tape gained a reputation for her skills as a landscape painter and amateur photographer. She also impressed white journalists with her ability to use a telegraph to send Morse code messages to her husband when he was at work.

Mary Tape died in 1934. Although she was ultimately unsuccessful in getting her children into the white public school, Tape v. Hurley became a landmark case addressing segregation in public schools. In 1947, the federal circuit court case Mendez v. Westminster ruled that school segregation of non-white minority children violated the Equal Protection Clause. California governor Earl Warren subsequently signed a law ending school segregation in California. About 70 years after Tape v. Hurley, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education finally ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in the United States.

Notes

[1] The city of San Francisco is a Certified Local Government.

Bibliography

Finding Aid for San Francisco Ladies' Protection and Relief Society records, MS 3576. California Historical Society. San Francisco, California. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt338nf0rf/.

Gamble, Leland. “What a Chinese Girl Did: An Expert Photographer and Telegrapher.” Morning Call (San Francisco), November 23, 1892.

Lee, Erika. “Immigration, Exclusion, and Resistance, 1800s-1940s,” Finding a Path Forward: Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks Theme Study. Edited by Franklin Odo. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/upload/04-Essay-4-immigration.pdf.

Martz, Carlton. “BRIA 23 2 c Mendez v. Westminster: Paving the Way to School Desegregation.” Bill of Rights in Action 23, no. 2 (Summer 2007). https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-23-2-c-mendez-v-westminster-paving-the-way-to-school-desegregation.

New York Historical Society. “We Have Always Lived as Americans.” Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion. September 26, 2014-April 19, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://chineseamerican.nyhistory.org/we-have-always-lived-as-americans/.

Ngai, Mae M. “That Chinese Girl.” Chap. 4 in The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Organization of American Historians. “Primary Source: Mary Tape, an Outspoken Woman.” OAH Magazine of History 15, no. 2 (Winter 2001), 17-19. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25163420.

Tape, Mary. “Letter from Mary Tape to the San Francisco Board of Education.” Daily Alta California (San Francisco), April 16, 1885.

Thomas, Heather. “Before Brown v. Board of Education, There was Tape v. Hurley.” Library of Congress (blog). Published May 5, 2021, https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/05/before-brown-v-education-there-was-tape-v-hurley/.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.