Last updated: July 18, 2025

Person

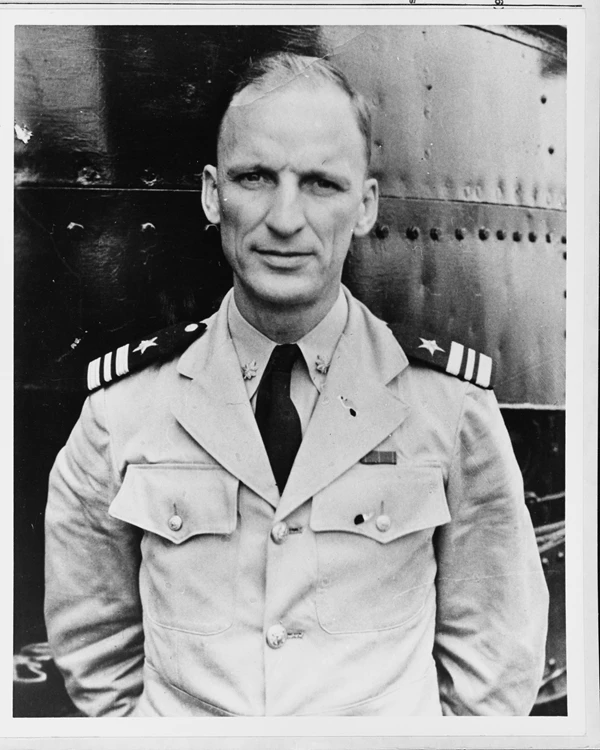

Mannert Abele

US Navy

Mannert “Jim” Lincoln Abele enlisted in the Navy at 17, in 1920 as an Apprentice Seaman. He rose through the ranks and eventually became Lieutenant Commander Abele on December 1, 1940. Abele also spent a year teaching Naval Science for the Naval Reserve Officers Training at Harvard University in 1939-1940. Over his career, he served on the battleships USS Utah and USS Colorado, and the submarines S-23, R-11, R-13, S-31, and USS Grunion. Abele always preferred to go by the name Jim, which is also what his children called him.

When Abele left his family for his last patrol in 1941, he was almost 39, and his children were 5 (John), 9 (Brad), and 12 (Bruce). He and his wife Catherine Eaton Abele had been married fifteen years.

On the USS Grunion’s way to Pearl Harbor from New London, CT, the crew encountered 16 survivors from the USAT Jack, which has been torpedoed by a German U-boat. They were able to rescue the 16 men, and looked unsuccessfully for the remaining crew, before taking them to safety at a Naval base in Panama. From Pearl Harbor, the Grunion sailed to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, to patrol.

By July 1942, the Grunion and Lt. Cmdr. Abele were patrolling off Kiska, which had been attacked and occupied by the Japanese during their attacks in early June. The last transmission from the Grunion was on July 30, 1942, and on August 1 she was listed as lost at sea, along with all 70 people on board.

As Abele’s son Brad recounts when he and his family learned the news, “That following September we received word via a forwarded telegram that the Grunion hadn’t been heard from since July 30, 1942 and was missing in action and presumed lost. I remember the day. It was an early fall, sunny afternoon and my brothers and I were playing with a football in the road out in front of our house in Newton Highlands, MA. My mother came to the door and called us all in and while we stood in a sunbeam by her desk in the front of the living room, she read us the “first” telegram. Bruce reacted with some exclamations, but I remember being completely devoid of emotional feeling at hearing the news. At that age, I was emotionally extremely phlegmatic. I have speculated that it was perhaps because my father had once told me that a “soldier” never cries (or at least that is what I thought) and I was more or less incapable of ever shedding tears from then on. After hearing the news and reflecting on its meaning for a short while, we returned to our activities out front which we continued to pursue rather listlessly. I remember that my mother never wanted to put any sort of a “gold star” in our window since she considered that the Grunion was officially “missing in action” and not definitely lost – yet.”

Catherine, Abele’s wife, was able to receive a year of pay for servicemen listed as “Missing in Action,” use Abele’s life insurance, and teach violin lessons to support her family. In April 1944, Catherine sponsored (christened the ship) a destroyer named the USS Mannert L. Abele. It was sunk off Okinawa, Japan in April 1945.

As an adult, Brad remembers, “Although I was only nine years old when Jim left for the war, I can remember a few things about him still. He was an exceptionally resourceful and excellent craftsman and turned out numerous impressive works made of wood, using only the most basic of tools. When he was not on duty, it seemed that what he loved most to do was to work around the house or in his workshop area. It seemed as if he never enjoyed “relaxing” in the traditional sense but would soon have to get up and start creating something. I remember only rarely ever playing with him in our yard, partly because he couldn’t throw overhand and had to pitch an object underhand instead, but also because it seemed he was always busy doing something else if he were around. The one amount of time he did allocate to each of his boys was when he would cut our hair and tell us stories while doing so. I remember well that he used a hand clipper that tended to pull the hair as he worked it, making the process rather uncomfortable for us.”

The USS Grunion was lost at sea for over 60 years, until August 2006, when a team spearheaded by the Abele brothers used side scan sonar to find a wreck that was a similar size and shape to the lost Grunion, in the location she was last seen. A year later, the team returned with a Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV) with HD video that clearly documented the ship. In October 2008, the US Navy confirmed the identity of the Grunion. In 2018, the bow of the Grunion was discovered a quarter mile away from the rest of the wreckage. The final resting place of Lt. Cmdr. Abele and his crew of 69 is now known, and provides solace for the families of the men missing in action since World War II.

Learn more about Lieutenant Commander Abele:

Naval History and Heritage Command's biography of Lt. Cmdr. AbeleNaval History and Heritage Command's entry on the USS Grunion

Brad Abele's recollections on his father and the USS Grunion (pdf)

The Lost 52 Project Expeditions to find the USS Grunion