Last updated: April 24, 2024

Person

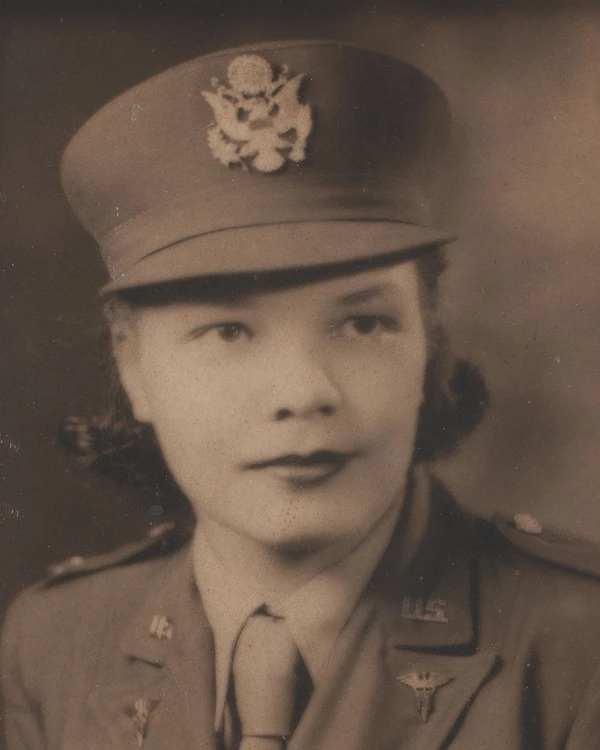

Louise Virginia Lomax

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Louise Virginia Lomax was born on January 27, 1920, in Crewe, Nottoway County, Virginia. Her parents were James and Annie Shepperson Lomax. Her father worked on the Norfolk and Western Railroad, while her mother was a homemaker. They lived in a four-room house with no plumbing or electricity, near the railroad tracks. Lomax was one of five children and the oldest daughter. Her mother relied on her to help around the house, especially when her father travelled for work. Lomax later recalled to her daughter, “I grew up in a time when we had very little. However, we were very happy and very proud because our parents instilled in us the importance of being responsible, being on time, being honest, and above all, to get that education because the education was a road to get a job, a professional job.”

When she was old enough to attend public school, Lomax and her siblings walked two-miles to the one-room schoolhouse. While they walked, they avoided the busses carrying white schoolchildren. The children on the bus would say racists things and throw stones at the family. Lomax attended the one-room schoolhouse until the seventh grade. Even though the Great Depression was making life hard for the family, Lomax’s maternal grandfather sent her to boarding school. Her grandfather, Reverend William Shepperson, sent Lomax and her sister, Capitola, to Ingleside-Fee Memorial Institute in Burkeville, Virginia. The school was run by the Presbyterian Church for African American children. While at school, Lomax kept to her schedule and was up early in the morning helping wherever needed. In 1938, Lomax graduated from Ingleside-Fee Memorial Institute and applied for nursing school. She recalled that growing up, “I knew there was a doctor in our town, in fact a family doctor, and his sister was a nurse and she trained in Richmond, Virginia, and I admired her, and I said, ‘Well, I want to be a nurse’ cause I liked to take care of people, and I liked to see people get well.’ I liked to see people lead good lives and [with] good health.” With her family’s encouragement, she applied to the St. Philip School of Nursing in Richmond, Virginia.

In September 1939, Lomax was accepted into the St. Philip School of Nursing at St. Philip Hospital, the segregated branch of the Medical College of Virginia. She was one of twenty-one nurses in her class. Three years later, in 1942, she graduated with her nursing diploma. In the fall of 1942, she passed the nursing exams for Virginia and became a Registered Nurse (RN). Lomax wanted to join the Army Nurse Corp (ANC) and serve her country. To be accepted in 1942 a woman had to be single, a member of the American Red Cross, a US citizen, a graduate of an accepted graduate school, have two years training as an RN in a hospital setting, and be a member of a national nursing organization. Discrimination made things difficult, especially when the American Nursing Association, one of the few national nursing organizations, only accepted white nurses.

While fighting discrimination, she received help from the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses’ Executive Secretary Mabel Staupers. She encouraged Lomax to keep trying and gave her their full support. The pressure from the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses was instrumental in convincing the Army to enlist Black nurses. The National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) was soon recognized by the US Army as a national organization. This allowed the member nurses of NACGN to fulfill all Army Nurse Corps requirements. The NACGN accepted Lomax as a member, and she was on her way to enlist.

While waiting on her acceptance into the US Army, Lomax continued working at St. Philip Hospital. On March 30, 1943, Lomax was inducted into the Army Nurse Corps as a second lieutenant. She was assigned to the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama. In July 1943, the commanding general of the Army Service Forces, Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell, mandated a formal four-week course for all newly commissioned nurses. According to author Pia Marie Winters Jordan, the training “stressed army organization, military customs and courtesies, field sanitation, defense against air, chemical and mechanized attack, personnel administration, military requisitions and correspondence and property responsibility.” This training opened opportunities for further nurse training. Over the next several years, the US Army offered new and diverse training opportunities for nurses that helped expand their careers.

The nurses at Tuskegee were not only caring for the aviation cadets, but also the officers, enlisted men, and families on base. The Office of Public Relations stated that “there is less bedside nursing in the army,” otherwise, a nurse’s work was not much different from a civilian hospital. Nurses were supervising the care and handling of patients, as well as administering medications and treatments. They were constantly training enlisted men to care for patients as well. Their schedule was hectic, thirty days and nights on duty or on call, then had twenty-four hours off. To keep monotony at bay, the nurses were rotated between the different services of medical, surgical, obstetrical, and gynecological. One of Lomax’s patients was Oliver Goodall. In an interview with Pia Jordan, the pilot recalled while he was “in the hospital with the mumps Lomax took excellent care of him saying she was the head nurse of that shift. They had three shifts and she made everyone jump. The way she would come to see you, she would have nothing but a pretty smile on her face and that was good because we needed that.” Lomax acquired several admirers while stationed at Tuskegee.

On February 12, 1944, Aviation Cadet Cleveland Clark wrote a poem dedicated to Lomax.

“She is truly an angel of mercy,

Bringing joy and gladness each day.

With cheerful words, and a teasing smile,

She always keep her patients gay.

All is well the whole day through,

Each patient’s face is gleaming with light.

But oh! Suddenly the lights are dimmed,

When she leaves for heaven each night.

Gee! I hate to see her go,

Tho’ time say we all must part.

Now she’s leaving, but she’ll never know,

That with her she’ll be taking my heart.”

Lomax also received a marriage proposal from another patient, which she kindly turned down. In 1945, she was promoted to first lieutenant.

In 1946, Lomax was transferred to Lockbourne Army Air Base near Columbus, Ohio. For her service during World War II, she was awarded the American Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal. In February 1948, Lomax was assigned to train at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC. St. Elizabeths was the first federally funded mental institution in the nation. There she learned about psychiatric health. The training was newly developed and lasted eight months.

In March 1949, she served at Percy Jones General Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. That same year, Lomax retired from active duty and joined the Army Nurse Reserves until 1953. Lomax returned to work as a civilian psychiatric chief nurse at St. Elizabeths Hospital until 1973. On April 1, 2011, Louise Lomax died and was buried at Bethesda Presbyterian Church in Crewe, Virginia.

References:

Marie Winters Jordan, Pia. 2023. Memories of a Tuskegee Airmen Nurse and Her Military Sisters. University of Georgia Press.

Threat, Charissa J. 2015. Nursing Civil Rights: Gender and Race in the Army Nurse Corps. Univ. of Illinois Press.

Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. 2004. G.I. Nightingales: The Army Nurse Corps in World War II. Univ. Press of Kentucky.