Last updated: December 9, 2020

Person

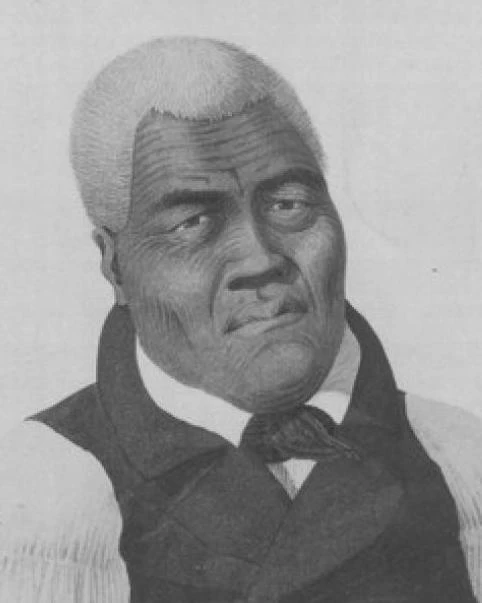

Kamehameha the Great

NPS photo of Louis Choris painting

| King Kamehameha was one of the most striking figures in Hawaiian history, a leader who united and ruled the islands during a time of great cultural change. Accounts vary, but many think that Kamehameha (originally named Pai'ea) was born into a royal family in North Kohala sometime between 1753 and 1761, possibly in November 1758. Kamehameha's mother was Kekuiapoiwa, daughter of a Kona chief. His father was probably Keoua, chief of Kohala. Legends link his birth to storms and strange lights, activities thought by Hawaiians to herald the birth of a great chief. Because of prognostications at his birth and threats from warring clans, Kamehameha was taken away and hidden immediately after his birth. He spent his early years secluded in Waipio, returning to Kailua at the age of five. He lived there with his parents until his father's death, then continued to receive special training from King Kalani'opu'u, his uncle. This training included skills in games, warfare, oral history, navigation, religious ceremonies, and other information necessary to become an ali'i-'ai-moku (a district chief). By the time of Cook's arrival, Kamehameha had become a superb warrior who already carried the scars of a number of political and physical encounters. The young warrior Kamehameha was described as a tall, strong, and physically fearless man who "moved in an aura of violence." Kamehameha accompanied his uncle (King Kalani'opu'u) aboard the Discovery, and history records that he conducted himself with valor during the battle in which Cook was killed. For his part in the battle at Kealakekua he achieved a certain level of notoriety, which he paraded "with an imperiousness that matched and even exceeded his rank as a high chief." Kamehameha might never have become king except for a twist of fate. Within a year after Cook's death, the elderly ali'i Kalani'opu'u, crippled by age and disease, called together his retainers and divided his Hawaiian domain. His son Kiwala'o became his political heir. To his nephew Kamehameha, the elderly ali'i entrusted the war god Kuka'ilimoku. Although this pattern of dividing the succession of the chiefdom and the protectorate of the god Ku was legendary, some authors suggest it was also uncommon. As the eldest son, a chief of high rank, and the designated heir, the claim of Kiawala'o to the island of Hawai'i was "clear and irrefutible." However, although Kamehameha was of lower rank, and only a nephew of the late king, his possession of the war god was a powerful incentive to political ambition. Thus the old chief's legacy had effectively "split the political decision-making power between individuals of unequal rank" and set the stage for civil war among the chiefs of the island of Hawai'i. Although Kiwala'o was senior to Kamehameha, the latter soon began to challenge his authority. During the funeral for one of Kalani'opu'u's chiefs, Kamehameha stepped in and performed one of the rituals specifically reserved for Kiwala'o, an act that constituted a great insult. After Kalani'opu'u died, in 1782, Kiwala'o took his bones to the royal burial house, Hale o Keawe, at Honaunau on the west coast of Hawai'i Island. Kamehameha and other western coast chiefs gathered nearby to drink and mourn his death. There are different versions of the events that followed. Some say that the old king had already divided the lands of the island of Hawai'i, giving his son Kiwala'o the districts of Ka'u, Puna, and Hilo. Kamehameha was to inherit the districts of Kona, Kohala, and Hamakua. It is not clear whether the landing of Kiwala'o's at Honaunau was to deify the bones of Kalani'opu'u or to attempt seizure of the district of Kona. Some suggest that Kamehameha and the other chiefs had gathered at Honaunau to await the redistribution of land, which usually occurred on the death of a chief, and to make hasty alliances. When it appeared that Kamehameha and his allies were not to receive what they considered their fair share, the battle for power and property began. Over the next four years, numerous battles took place as well as a great deal of jockeying for position and privilege. Alliances were made and broken, but no one was able to gain a decisive advantage. The rulers of Hawai'i had reached a stalemate. Kamehameha's superior forces had several times won out over those of other warriors. He took the daughter of Kiwala'o, Keopuolani, captive and made her one of his wives; he also took the child Ka'ahumanu (once mentioned as a wife for Kiwala'o) and "betrothed her to himself." He thus firmly established himself as an equal contender for control over the Hawaiian lands formerly ruled by Kalani'opu'u. Eventually Kiwala'o was killed in battle, but control of the Island of Hawai'i remained divided. By 1786 the old chief Kahekili, king of Maui, had become the most powerful ali'i in the islands, ruling O'ahu, Maui, Moloka'i, and Lana'i, and controlling Kaua'i and Ni'ihau through an agreement with his half-brother Ka'eokulani. In 1790 Kamehameha and his army, aided by Isaac Davis and John Young, invaded Maui. The great chief Kahekili was on O'ahu, attempting to stem a revolt there. Using cannon salvaged from the ship, the Fair American, Kamehameha's warriors forced the Maui army into retreat, killing such a large number that the bodies dammed up a stream. However, Kamehameha's victory was short-lived, for one of his enemies, his cousin Keoua, chief of Puna and Ka'u, took advantage of Kamehameha's absence from Hawai'i to pillage and destroy villages on Hawai'i Island's west coast. Returning to Hawai'i, Kamehameha fought Keoua in two fierce battles. Kamehameha then retired to the west coast of the island, while Keoua and his army moved southward, losing some of their group in a volcanic steam blast. This civil war, which ended in 1790, was the last Hawaiian military campaign to be fought with traditional weapons. In future battles Kamehameha adopted Western technology, a factor that probably accounted for much of his success. Because of Kamehameha's presence at Kealakekua Bay during the 1790s, many of the foreign trading ships stopped there. Thus he was able to amass large quantities of firearms to use in battle against other leaders. However, the new weapons were expensive and contributed to large increases in the cost of warfare. After almost a decade of fighting, Kamehameha had still not conquered all his enemies. So he heeded the advice of a seer on Kaua'i and erected a great new heiau at Pu'ukohola in Kawaihae for worship and for sacrifices to Kamehameha's war god Ku. Kamehameha hoped to thereby gain the spiritual power that would enable him to conquer the island. Some say that the rival chief Keoua was invited to Pu'ukohola to negotiate peace, but instead was killed and sacrificed on the heiau's altar. Others suggest that he was dispirited by the battles and was "induced to surrender himself at Kawaihae" before being killed. His death made Kamehameha ruler of the entire island of Hawai'i. Meanwhile, Kahekili decided to take the advantage while Kamehameha was preoccupied with Keoua and assembled an army — including a foreign gunner, trained dogs, and a special group of ferociously tattooed men known as pahupu'u. They raided villages and defiled graves along the coasts of Hawai'i until challenged by Kamehameha. The ensuing sea battle (Battle of the Red-Mouthed Gun) was indecisive, and Kahekili withdrew safely to O'ahu. Shortly thereafter, the English merchant William Brown, captain of the thirty-gun frigate Butterworth, discovered the harbor at Honolulu. Brown quickly made an agreement with Kahekili. The chief "ceded" the island of O'ahu (and perhaps Kaua'i) to Brown in return for military aid. Kamehameha also recognized the efficacy of foreign aid and sought assistance from Captain George Vancouver. Vancouver, a dedicated "man of empire," convinced Kamehameha to cede the Island of Hawai'i to the British who would then help protect it. Kamehameha spent the next three years rebuilding the island's economy and learning warfare from visiting foreigners. Upon Kahekili's death in 1794, the island of O'ahu went to his son Kalanikupule. His half-brother Ka'eokulani ruled over Kaua'i, Maui, Lana'i, and Moloka'i. The two went to war, each seeking to control all the islands. After a series of battles on O'ahu and heavy bombardment from Brown's ships, Ka'eokulani and most of his men were killed. Encouraged by the victory over his enemies, Kalanikupule decided to acquire English ships and military hardware to aid in his attack on Kamehameha. Kalanikupule killed Brown and abducted the remainder of his crew, but the British seamen were able to regain control and unceremoniously shipped Kalanikupule and his followers ashore in canoes. Recognizing his enemy's vulnerability, Kamehameha used his strong army and his fleet of canoes and small ships to liberate Maui and Molaka'i from Kalanikupule's control. Kamehameha's next target was O'ahu. As he prepared for war, one of his former allies, a chief named Kaiana, turned on him and joined forces with Kalanikupule. Nevertheless, Kamehameha's warriors overran O'ahu, killing both rival chiefs. Kamehameha could now lay claim to the rich farmland and fishponds of O'ahu, which would help support his final assault on Kaua'i. By mid-1796, Kamehameha's English carpenters had built a forty-ton ship for him at Honolulu, and once again he equipped his warriors for battle and advanced on Kaua'i. However bad weather forced him to give up his plans for invasion. Meanwhile yet another challenger — Namakeha, Kaiana's brother — led a bloody revolt on Hawai'i, depopulating the area and forcing Kamehameha to return to Hawai'i to crush the uprising. Kamehameha used the next few years of peace to build a great armada of new war canoes and schooners armed with cannons; he also equipped his well-trained soldiers with muskets. He sailed this armada to Maui where he spent the next year in psychological warfare, sending threats to Ka'umu'ali'i, Kaua'i's ruler. This proved unsuccessful, so early in 1804 Kamehameha moved his fleet to O'ahu and prepared for combat. There his preparations for war were swiftly undone by an epidemic, perhaps cholera or typhoid fever, that killed many of his men. For several more years he remained at O'ahu, recovering from this defeat and, perhaps, pondering conquest of Kaua'i. Expecting an attack from Kamehameha, Ka'umu'ali'i sought the help of a Russian agent, Dr. Georg Schaffer, in building a fort at the mouth of the Waimea River and exchanged Kaua'i's sandalwood for guns. However, the anticipated battle never came because an American trader convinced Kamehameha to reach a compromise with Ka'umu'ali'i. Kamehameha was acknowledged as sovereign while Ka'umu'ali'i continued to rule Kaua'i, with his son as hostage in Honolulu. After nine years at O'ahu, Kamehameha made a lengthy tour of his kingdom and finally settled at Kailua-Kona, where he lived for the next seven years. His rise to power had been based on invasion, on the use of superior force, and upon political machinations. His successful conquests, fueled by "compelling forces operating within Hawaiian society," were also influenced by foreign interests represented by men like Captain Vancouver. Kamehameha died in May of 1819. He had accomplished what no man in the history of the Hawaiian people had ever done. By uniting the Hawaiian Islands into a viable and recognized political entity, Kamehameha secured his people from a quickly changing world. |