Last updated: January 15, 2022

Person

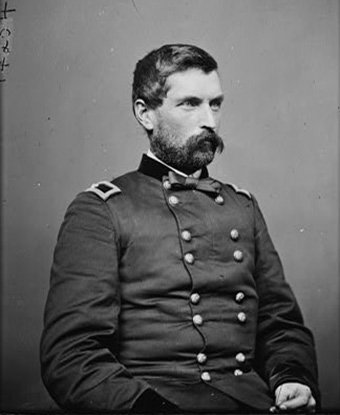

Brigadier General John Gibbon

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

By Dr. Donna L. Sinclair

Brigadier General John Gibbon stands among the longest serving commanders of the Department of the Columbia, headquartered at Vancouver Barracks. His tenure (1885-1891) occurred during a period of consolidation and entrenchment of US Western colonial power, a period of great change as the military turned its attention away from conflict with American Indians and towards imperial efforts overseas.

Gibbon arrived at Vancouver Barracks in 1879. Just six years earlier, the headquarters of the Department of the Columbia had returned to Vancouver, after a brief period of being located in Portland, Oregon. Gibbon arrived in Vancouver just in time for the modernization that prepared the United States for its role as a world power in the century that followed. During this late 19th century, technological innovations, such as the telephone, tied together military and civilian communication. These innovations connected the barracks not only to the local community, but also to the nation, and, eventually, the world. Combined with the great expansion of Vancouver Barracks after 1876, advances in communications also made possible rapid responses to regional crises, including the expulsion of Chinese people from Seattle in 1885 and, later, quelling labor unrest in the mines of Idaho.

John Gibbon took command of the Department of the Columbia on July 29, 1885, in charge of 139 officers and 1,661 enlisted men. Gibbon's command followed that of Civil War heroes like Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard (1874-1880) and Nelson A. Miles (1881-1885). Also a key Civil War figure, Gibbon has been remembered primarily for leading the Iron Brigade and participating in the commission that accepted the surrender of the South at Appomattox. However, examining Gibbon's career from the perspective of Vancouver Barracks provides additional insight into one of the longest-serving commanders at Vancouver Barracks.

Gibbon was a family man and officer, a southern Democrat and a Union patriot, a leader and a non-conformist, a man who reinforced American colonialism and resisted Victorian norms. In Vancouver, he encountered a military post renamed "Vancouver Barracks" in 1879, a recently renovated military site that appeared to an 1885 visitor as the "principle military post of the Pacific Northwest...destined to become more important than now in view of its location to the balance of the department."1

Early Life and Military Experience

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 20, 1827, John Gibbon was the fourth of ten children in a slaveholding family from North Carolina. Gibbon had a typical pre-Civil War career trajectory. He took five years to graduate from West Point in 1847 and then served in Florida, as military action sought to prevent conflict between the Seminoles and settlers. He then served in the Mexican War with the 3rd Artillery. Gibbon later taught artillery tactics at West Point, where he wrote a seminal scientific treatise on gunnery used by both sides during the Civil War.

When the Civil War broke out, Gibbon remained loyal to the Union, despite three brothers, two brothers-in-law, and a cousin who joined the Confederate Army. He gained significant battle experience, from the Second Battle of Bull Run to Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Petersburg. After the war, he went on to serve as the central commander at the Battle of Big Hole during the Nez Perce War (1877). Although the Nez Perce suffered more casualties than the US Army, this battle changed the course of the conflict and set the Nez Perce on the path to Canada.2

Gibbon later became a prolific writer, producing personal recollections of the Civil War and over two dozen magazine articles on subjects that ranged from analyses of Big Hole and other conflicts with Native people, to women's rights. Gibbon's annual departmental reports also provide significant insight into army practices and his own increasingly progressive thinking.3

John Gibbon and Family

Gibbon and his wife, Frances "Fannie" North Maole, whom he met during his West Point school days, had four children: Frances "Little Fannie" Maole Gibbon, Katharine "Katy" Lardner Gibbon, John Gibbon, Jr., who died at twelve days old, and John S. Gibbon, Jr. After the Civil War, the Gibbon family moved West, placing Frances Gibbon among the army wives who experienced the rigors of traveling cross country.

Soon after reaching Vancouver, 27-year-old Katy Gibbon wed Lieutenant James Espy McCoy in the Department of the Columbia commander's house (now called the O.O. Howard House) on October 28, 1885. They held an elegant, "fashionable" afternoon affair, with a few select guests. Lieutenant McCoy of the 7th Infantry wore his dress uniform, she a white silk dress garnered with lace. The flowers were "simple but elegant," with radiant perfumed exotics flaking the marble mantle piece. Reflecting the family's status, Archbishop Gross of Oregon, assisted by Vancouver's Father Schramm, performed the Roman Catholic ceremony. Congratulations and conversation followed the ceremony. An elegant luncheon in the dining room followed the reception. When the couple said goodbye, Mr. and Mrs. Gibbon gave them a "sad farewell." Katy and James went off to Portland, Oregon, that night, and left for his duty station at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, within days.4 Young Katy was on her way to becoming a frontier officer's wife, like her mother.

James and Katy McCoy had a child while in Wyoming, and then in January of 1887, General Gibbon detailed his son-in-law as aide de camp. Katy and James returned to Vancouver Barracks.5 It is not clear if Katy joined in the family's theatrical actibvities while at the barracks. At the very least, she surely attended performances that included General Gibbon, his daughter Fannie, and son John, Jr., who often performed together in small plays, alongside other officers from the post.

In the early months of 1888, General Gibbon and John, Jr., went to Walla Walla, Washington, where John, Jr., contracted pneumonia. In Vancouver, Katy also became sick. She became so ill that General Gibbon received a telegram requesting his return as quickly as possible. His daughter was dying. He may not have arrived in time, as the same newspaper column that noted the general's beckoning also reported the following:

Katy Gibbon was buried in the recently established Fort Vancouver Military Cemetery. John, Jr., recovered. It is not clear what happened to Katy McCoy's two young children, but they later lived with their grandmother, Frances Gibbon. Within a year and a half of Katy's death, James McCoy returned to Wyoming. On July 27, 1889, the Cheyenne Daily Leader reported that Lieutenant McCoy, General Gibbon's son-in-law and, until recently, a member of his staff, died suddenly at Camp Pilot Buttes of erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection.8"Mrs. Katharine L. McCoy, wife of Lieut. McCoy, U.S. army, died Friday afternoon. Her youngest child is 2 1/2 months old. Pneumonia was the cause of death. The funeral took place on Sunday, with all the honors due to a soldier's daughter and a soldier's wife. The event casts a deep gloom of sadness over the people in both barracks and town, as Mrs. McCoy was much esteemed, and a general favorite."7

General John Gibbon and Chinese Expulsion

Nearing retirement when he became a Brigadier General at Vancouver Barracks, John Gibbon had developed clear ideas about how the US Army should work, and he seemingly had no qualms about anticipating orders or weighing in on the issues of the day. Nowhere was Gibbon's impatience with military bureaucracy clearer than in his response to civil unrest surrounding immigrants from China.

Starting in the 1850s, harsh economic and political conditions in China prompted laborers to leave, usually with plans to eventually return to their native country. At the same time, the United States - the land the Chinese called "gum saan" or "gold mountain" - sought laborers to work on the transcontinental railroads. The Northern Pacific Railroad employed more than 21,000 Chinese laborers for its line through Montana, Idaho, and Washington territories. Although many Chinese men9 worked on railroads, they also engaged in occupations like gold mining, ditch digging, logging, and as servants and cooks in the households of military officers and other well-to-do civilians. Others became entrepreneurs, and Chinese stores and laundries became increasingly common. By 1880, approximately 105,000 Chinese people lived in the United States. In that decade, anti-Chinese sentiment erupted on the West Coast, where the largest number of Chinese immigrants lived.

Xenophobia (fear of others) and racism had resulted in anti-Chinese violence along the Northwest Coast in the 1880s. White laborers pushed for the expulsion of Chinese workers and called for a ban on further immigration. Chinese women had been barred from entering the US through the 1875 Page Act. A new law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, extended that ban to all Chinese people. Passed in 1882, the law provided an absolute moratorium on Chinese workers, "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining," entering the United States. It also required deportation of any Chinese who arrived after 1880, essentially banning all Chinese people, save a very few with Chinese government sanction. The ban also made it difficult for Chinese immigrants to leave the country and then reenter. Congress renewed the act again in 1892, and again in 1902, adding the requirement that all Chinese get a certificate of residence or face deportation.

With rising anti-Chinese sentiment during economic downturns, the exclusion law "spurred rather than deterred violence."10 Around the Northwest, assault, murder, and expulsion of Chinese residents occurred without consequence. In 1885, the year that General Gibbon took command of the Department of the Columbia, gangs of white miners murdered 28 Chinese men and injured 15 in Rock Springs, Wyoming. For several months that fall, Tacoma, Washington's community leaders agitated to remove approximately 700 Chinese who lived in the city. They held town meetings, made threats, and met in Seattle as a Committee of 15 at an anti-Chinese Congress on September 28, presided over by Tacoma Mayor Jacob Robert Weisbach. The group ordered all Chinese to leave the region by November 1, 1885, with posters declaring "The Chinese Must Go!" marking the town for months. Many Chinese people left voluntarily. The rest experienced a large-scale forceful ousting, soon known as the "Tacoma Method." On November 3, 1885, several "committees" led by Mayor Weisbach and the Tacoma Police raged through town, bursting into Chinese homes and businesses alike to expel them from the city.

A Tacoma merchant, Lum May, described his experiences in an affidavit on November 3, 1885:

On November 4, 1885, Governor Watson Squire issued a proclamation calling for a halt to violence and intimidation, asking citizens, police, and other officials to stand with the law. Still, low-level violence erupted in Seattle, where many feared "a repetition of the outrages" in Tacoma. This is when the Army entered the picture. On November 8, 1885, the War Department ordered ten companies of the 14th Infantry from Vancouver Barracks to Seattle, and they arrived to a "perfectly quiet" town. The next day, four companies traveled by rail to Tacoma, where they received prisoners from the United States Marshal, took them to Vancouver, "and, after turning them over to the United States Court, rejoined the post." The remaining six companies stayed in Seattle until November 17, but took "no action," as the city remained peaceable. Over the next few months, more than half of Seattle's Chinese residents left the city. Approximately 350 to 400 remained in early 1886.11"Where the doors were locked they broke forcibly into the houses, smashing in doors and breaking in windows. Some of the crowd were armed with pistols, some with clubs. They acted in a rude, boisterous, and threatening manner, dragging and kicking the Chinese out of their houses. My wife refused to go, and some of the white persons dragged her out of the house...From the excitement, the fright, and the losses we sustained through the riot she lost her reason. She was hopelessly insane and attacked people with a hatchet or any other weapon if not watched... The outrages I and my family suffered at the hands of the mob has utterly ruined me...My wife was perfectly sane before the riot...I saw my country men marched out of Tacoma on November 3rd. They presented a sad spectacle."

The short-lived calm ended on February 7, 1886, as Seattle mobs lashed out. The day began quietly, with groups of four or five men at a time entering the Chinese quarter, ostensibly for a sanitary inspection (based on overcrowding), but their true purpose was expulsion. Seattle's police chief and other officers accompanied the group as they "hauled out" goods from the homes of Chinese residents and sent them by wagon to the Queen of the Pacific, a ship docked at the foot of Main Street. By mid-morning, a large crowd gathered and the volunteer militia, the Seattle Home Guard and Seattle Rifles, and the University Cadets, assembled in response. Although Seattle's sheriff had originally brought together a smaller posse, by afternoon a huge mob pushed 300 Chinese residents to the docks, where the ship's captain refused to allow them onboard without fare. The mob quickly collected enough money to send a hundred Chinese away and returned the others to the Chinese quarter.12

When he heard what was happening, General John Gibbon rapidly readied troops to go to Seattle. The next day, February 8th, "still more urgent calls came from the Governor and others" when conflict ensued between the mob and civil authorities. Still, Gibbon awaited orders from the president. That morning, after the Queen took another 196 people away, a mob of up to 2,000 people attacked the guards, escorting the remaining Chinese away from the dock to wait for the George W. Elder, due a few days later. At that point, Gibbon took matters into his own hands, sending eight companies to the post wharf, putting them on a steamer heading north to Kalama, Washington, arranging for further transport to Seattle, then waiting for orders to proceed. Finally, at 9 pm, Gibbon received direction to proceed to Seattle with the troops "necessary to suppress domestic violence, and aid the civil authorities in overcoming obstruction to the enforcement of the law."13 One person had been killed and several others were injured.

By the time Gibbon's troops arrived on February 10, 1886, the governor had declared martial law. The general found the city "perfectly quiet and peaceful," with little evidence of the need for troops. Citizen militia had quelled the "riotous proceedings." The military immediately "placarded" the city with notices of the president's proclamation against civil disorder and closed "[b]usiness houses and saloons" early each day, while troops relieved the militia from street patrol. General Gibbon expressed disgust for the entire situation. Not only had he been ready to move troops immediately, but he claimed that Seattle's leaders were "...responsible for the shedding of blood" because they "undertook deliberately and with 'malice aforethought,' to violate th[e] law, and induce others to do it."

The governor, noted Gibbon, had let the situation get out of hand: "[H]ad there been a few good policemen, duly instructed in their duty as guardians of society, there is no question in my mind that no such sense as had disgraced the streets of this city would ever have been enacted." With better training, martial law, an "additional disgrace" when placed "over the heads of American citizens," could have been avoided altogether. Gibbon called for the immediate arrest of "every known leader of the outrages." He wrote to the governor, "These men who, by inciting others to violations of the law, and, in some cases, aiding in it themselves, are well known to yourself and the civil authorities of the city."14

On February 16, 1886, Adjutant General Richard Coulter Drum admonished Gibbon for a second time in relation to the events in Seattle. His first reprimand expressed clear dissatisfaction that Gibbon had acted on his own. "While no fault is found with any preparation you may have made in anticipation of orders," Drum wrote, "the Secretary of War thinks it would have been the part of wisdom to keep secret any contemplated movement of troops, especially connected with civil trouble."15 The second rebuke stemmed form complaints by Governor Squire that General Gibbon overstepped his bounds by making arrests, though he clearly had the authority to do so. Drum chided Gibbon, saying Gibbon misunderstood "the purpose for which the troops were sent to Seattle." Drum wrote that the troops were not meant to be a "posse" in place of local authorities, "but [there] to preserve the peace, give security to life and property, and prevent obstruction to the enforcement of the laws," wrote Drum. "Dispatch of to-day [February 16] is received," responded Gibbon immediately.16

Gibbon responded that he had arrived in Seattle on February 10, preceded by eight companies of the 14th Infantry. His orders to "aid the civil authority and assist in the execution of the law" prompted him to arrest some "of the instigators and leaders of the late violations of the law" and place them "under guard" to prevent further violence. Martial law had been "perfectly justifiable," claimed Gibbon, but since police composed part of the mob, they had threatened members of the militia.17 Gibbon maintained that "no one indicted for a crime connected with the anti-Chinese movement can by any possibility be convicted by any jury that can be had here." Bitterness reigned in Seattle because of the bloodshed, "and the fear now is that as soon as the protection of martial law is removed" civil authorities would be "sacrificed to the fury of the disorderly party" unless the violators were punished. Thus, the arrests.

Gibbon made another important point regarding the national implications of the "Chinese question" as a broad assault on civil liberties, not just for Chinese residents, but also for American citizens. Chinese expulsion demoralized the American people by "degrading their sense of liberty, justice, and freedom." This degradation stemmed both from martial law and "self-appointed regulators," who invaded private houses and demanded the discharge of Chinese servants. People submitted "almost without protest; certainly without the proper kind of protest in a case where the rights of American citizenship have been so grossly outraged." So disturbed was he that Gibbon requested his communication "be laid before the President of the United States." While Gibbon remained far away, Drum operated as adjutant general of the Army, with his physical location in Washington, D.C. Just underneath Gibbon's February 16, 1886, report on the Chinese trouble and his request for the president to hear more about the situation is the statement, "No reply to this report has been received."18

The following day, the Provost Marshal of the city turned over nine prisoners to the territorial marshal. Gibbon noted that "Appropriate proceedings were held," with the prisoners disposed of "by bail or otherwise with the decision of the Commissioner." At that point, leaders allowed stores and saloons to re-open and daily business gradually recommenced. By February 22, Gibbon told the governor he no longer saw a need for martial law. The next day, Governor Squire's proclamation removing martial law appeared in the morning papers and civil authorities took control of the city. Four military companies returned to Vancouver on February 25th. Two remained until April 2nd, and the final two companies, slated to withdraw on May 5th, stayed in Seattle until August 19, 1886.

Gibbon noted that violence against Chinese continued in the region, with a number of laborers expelled from Douglas Island in Alaska Territory by "an organized party of white men, who acted with great brutality towards their helpless victims." A "gang of horse thieves and schoolboys from Wallowa County"19 massacred up to 34 Chinese gold miners in Hells Canyon a year later, without prosecution. Disgusted but exhibiting his own prejudices toward immigrants, Gibbon complained about disregard for the law, which "furnishes the opportunity for the shiftless and improvident, largely composed of foreign elements, to attempt to dictate as to who shall and who shall not perform certain labor." Perhaps worse, the very men who forced the Chinese out were "themselves unwilling or incapable of performing" the kinds of labor done by the Chinese.20

John Gibbon, the Commander

General John Gibbon had strong feelings about many other issues, ranging from the size of garrisons and the Army response to desertion, to the military's relationship with Native people. Regarding garrison size, he reported troops in the Department in "satisfactory condition" in 1886, with "discipline, drill, and general efficiency" resulting from the larger garrisons, as indicated by decreased desertions, which he found "very gratifying (90 against 165 the previous year). The courts also tried 201 fewer cases in 1886 (79 by general courts and 122 by minor courts), demonstrating "the improved state of discipline amongst the troops." Larger posts held more courts-martial, with the largest number coming from Vancouver Barracks, though not the largest percentage of cases. Fort Coeur d'Alene took that prize, with 88 cases, and Boise Barracks held the fewest, with 27 cases.21

Throughout the rest of Gibbon's tenure, he kept troops at the ready through summer exercises meant to simulate battle conditions. In 1888, the 14th Infantry moved over rough mountain roads of the Coast Range to Nestucca Bay. The next year, one group traveled by boat to The Dalles and marched into Cayuse Indian territory near Pendleton, Oregon. Another group, under Lieutenant Charles Martin (later governor of Oregon), took supplies for the journey over the old "narrow, crooked, and very rocky" Barlow Trail. Fifty men and 22 six-horse "prairie schooners" headed through Gresham and Sandy to Mount Hood, where the difficult topography slowed them to just a few miles per day. After reaching The Dalles via the Tygh Valley and over the Deschutes River, troops halted to repair the Civil War era wagons that then took them through Indian villages west and south of Pendleton, "just to let the tribes know that they were on the job," said Martin. With maneuvers over, troops returned to Vancouver and prepared for immediate mobilization. Such preparation became necessary in the years that followed as the US government shifted from American colonial expansion to overseas engagement in Cuba, the Philippines, China, and the world wars of the 20th century.22

In his final days as commander of the Department of the Columbia, John Gibbon neared 50 years as a soldier. He had also solidified his feelings about Native/non-Native relations. Like all commanders since the 1850s, Gibbon contended with calls from settlers to "quiet" Native people. In 1886, the same year he addressed the graduating class at West Point, he reported conflicts over reservation boundaries on the Klamath Reservation. Troops were "invoked," wrote Gibbon, "but the mere presence of the Agent was sufficient to settle the difficulty." Reservation lines should be drawn more distinctly, he observed. That year, settlers accused the Kalispel of "serious outrages...murdering settlers and stealing stock to the north of Spokane Falls, [Washington Territory]." The Army dispatched troops from Fort Coeur d'Alene to protect settlers in Clark Fork Valley and reports of additional "outrages" resulted in sending two more companies there. The first troops (infantry) moved north until they met the second (cavalry) and, in an oft-repeated pattern, found the alarming reports "entirely and utterly groundless." The infantry returned to its post and leaders withdrew the cavalry. Military leadership seemingly sent troops out to scare Native people into full submission, and by the end of the decade most conflict halted. There would be additional incidents well into the 1890s, but they remained few and far between.23

Gibbon, who had commanded the Montana Column in 1876 as it rescued survivors and buried the dead after the 7th Cavalry's battle with the Teton Sioux and Northern Cheyenne on the Little Bighorn River, often recognized injustices against Native people. Despite his own participation, he also lamented the destruction, death, and intensive grief wrought upon the Nez Perce at Big Hole in 1877, when 89 Native men, women, and children were killed. 29 Army soldiers were killed in the conflict. Although he considered the deaths of the women and children at Big Hole "unavoidable," his testimony before a congressional committee in 1878 revealed his feeling that the Nez Perce Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt,24 known to whites and Gibbon as Chief Joseph, along with "his band" had been objects of the greatest possible injustices at the hands of the government. "The management of [the Nez Perce]," by the Indian Department had "actually forced [them] into rebellion," he said.25 That may be why, as commander of the Department of the Columbia, Gibbon tried to help the Nez Perce after their return to the Northwest.

Joseph's band spent nearly eight years in Indian Country in Oklahoma before General Nelson Miles brought them back to the Colville Reservation in Washington State in 1885, the year Gibbon replaced Miles at Vancouver Barracks. In 1889, Gibbon met with Joseph at Lake Chelan, where he learned of the difficulties the band faced on the reservation. There had been no overt "acts of hostility," but some Colville who did not want them there made life difficult for the Nez Perce. For example, someone repeatedly moved stakes placed to mark land claims, causing conflict and confusion. Although Joseph had complained to Washington, D.C., the harassment became worse and Nez Perce cattle were hamstrung or shot. In telling this story, Joseph appeared to Gibbon as having "about given up all hope" of becoming comfortably established. Although Joseph made no charges against any individuals, Gibbon learned through the interpreter, Mr. Chapman's "personal knowledge" and the "closest cross-examination" that the "medicine-man" Sko-las-kin led the agitation to remove the Nez Perce.26

Gibbon turned to the commander at Fort Spokane and the Indian Agent on the Colville Reservation, calling for Sko-las-kin's arrest and removal from the reservation. A month later, he received authority to arrest Sko-las-kin, who "denied all knowledge of the hostile acts against Joseph and his people." Still, the Army first sent the medicine man to Vancouver for trial and then to prison at Alcatraz. Gibbon ensured that those associated with Sko-las-kin knew why he was imprisoned, and all "troubles ceased at once." Gibbon later described the incident as an example of sacrificing the "liberty of one individual" for the "welfare of the many" by using the power of the government.27

A few months after his visit to Lake Chelan, John Gibbon invited Joseph to Vancouver Barracks, where the "ladies of the station" entertained him at breakfasts and the general spent many long hours in discussion with him. During the visit, a Portland newspaper reiterated the rumor begun during the Nez Perce War that Gibbon's troops had been saved by General Howard's command. For the first time in all their interactions, Gibbon spoke about the events at Big Hole with Joseph, who confirmed that "he did not know anything about General Howard being near" before he left Big Hole Pass. This confirmation likely contributed to Gibbon's efforts to ensure the Nez Perce had clothing the following winter through the contributions of a Portland philanthropist.

Later Years

Although still officially in charge of the Department of the Columbia, General Gibbon left Vancouver for San Francisco in 1890 to command the Division of the Pacific. John Gibbon's rise in the Army had taken him from Florida to the Plains to West Point, New York, and into engagements all over the South, from Gettysburg to Bull Run and Antietam to Pickett's Charge and beyond. He left the war years as a captain in the regular army, with five brevets obtained as a Commander of Volunteers during the Civil War. In December 1866, John Gibbon had become a colonel, harkening a slower rise than many of his fellow West Point graduates. Twenty-five years later, in 1891, he retired as a brigadier general and returned to his family home in Baltimore, Maryland, where he continued writing his recollections and essays. There, on February 6, 1896, at age 70, John Gibbon died from complications of pneumonia. His wife Fannie died a few years later.

General Gibbon's time at Vancouver Barracks occurred as the US cemented its colonial takeover of Native lands. His career spanned from the Seminole Indian Wars to the end of military conflict with American Indians in the Pacific Northwest and on the Plains by 1890. Like many others of his generation, he understood the complex nature of Native/non-Native relations, and tried to compensate for some of the failings of the United States government. He also questioned the racial policies of civilian leaders in Seattle and recognized the dangers of imposing unwarranted power through martial law.

By century's end, Vancouver Barracks existed in an urban setting, a place where military and civilian leaders forged economic and political connections that extended into subsequent generations. General John Gibbon took part in shaping those relationships. From weddings to theater to social events on the Parade Ground, General Gibbon participated in the region's social life, even as he grappled with questions of appropriate levels of military authority and the morality of 19th century racial politics. General John Gibbon, soldier, father, husband, and philosopher, was a complex man who helped to shape society in the Pacific Northwest and who, in turn, was changed by his time at Vancouver Barracks.

Notes

1. "Vancouver. As Described by an Iowa Man," Vancouver Independent, Vol. 10, no. 50 (July 10, 1885), 5.

2. John Gibbon, Alan D. Gaff, and Maureen Gaff, Adventures on the Western Frontier (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1994), xiii.

3. Gaff, Adventures, xv.

4. "The McCoy Gibbon Wedding," Oregonian (November 1, 1885), 7.

5. "Katherine Lardner 'Katy' Gibbon McCoy," https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/20018135 (accessed October 16, 2018); Vancouver Independent, Vol. 12, no. 22 (January 12, 1887).

6. Duane Hennessey, "Charles Martin," Oregonian (December 4, 1938), 82.

7. Vancouver Independent, Vol. 13, no. 28 (February 22, 1888).

8. "Died at Pilot Buttes," Cheyenne Daily Leader (July 27, 1889), 3; Army Navy Journal, August 3, 1889; "Erysipelas," Medscape, (accessed October 16, 2018); "Erysipelas," Merck Manual, Professional Version (accessed October 16, 2018)

9. For more information about the exclusion and status of Chinese women, see Peggy Nagae, "Women: Immigration and Citizenship in Oregon" Oregon Historical Quarterly, 113, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 334-359. Note that by 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act restricted all immigration from China and only allowed the wives of merchants to enter the United States.

10. David Jepsen and David Norberg, Contested Boundaries: A New Pacific Northwest History (Wiley Blackwell Publishers, 2017), 186.

11. Phil Dougherty, "Mobs violently expel most of Seattle's Chinese residents, beginning on February 7, 1886," Historylink essay no. 2745, History link (November 17, 2013), available at http://www.historylink.org/File/2745 accessed June 9, 2018; Department of the Columbia Annual Reports, Report of Brigadier General John Gibbon, Commanding the Department of the Columbia Headquarters Department of the Columbia (Vancouver Barracks, W.T.: Adjutant General's Office, September 8, 1886), 1.

12. Dougherty, "Mobs expel Seattle Chinese."

13. Dougherty, "Mobs expel Seattle Chinese"; Gibbon, 1886 Annual Report, 2.

14. Gibbon, 1886 Annual Report, 3-4; The impulse to violence spread around the region. In 1886, the Vancouver Independent reported on a plan to "go to La Camas to dispose of the few Chinamen in that locality." The "bloody project was given up" for some unknown reason, observed the paper Vancouver Independent, Vol. 11, no. 28.

15. Gibbon, 1886, 2.

16. Gibbon letter, February 16, 1886, in Gibbon, 1886, 4-5.

17. Gibbon, 1886, 5.

18. Gibbon, 1886, 6.

19. Gregory Nokes, "Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek," Oregon Encyclopedia, accessed March 25, 2019. See also, Gregory Nokes, Massacred for Gold: The Chinese in Hells Canyon (Oregon State University Press, 2009).

20. Gibbon, 1886, 6, 7.

21. Gibbon, 1886, 8, 9.

22. Duane Hennessey, "Charles Martin, Chapter II," Oregonian (Dec. 11, 1938), 89.

23. Adjutant General's Office, "Report of Brigadier General John Gibbon, Commanding the Department of the Columbia. Headquarters Department of the Columbia, Vancouver Barracks, W.T." (September 8, 1886), 6-8.

24. Chief Joseph's Native name, Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, means "Thunder Rising to Loftier Heights," West, Last Indian War, 51.

25. In John Gibbon, Adventures on the Western Frontier, Alan and Maureen Gaff, eds. (Indiana University Press, 1994), 174, 217.

26. Gibbon, Adventures, 220-222.

27. Gibbon, Adventures, 222.

28. Alan and Maureen Gaff, Adventures, xiv-xvi.