Last updated: June 17, 2022

Person

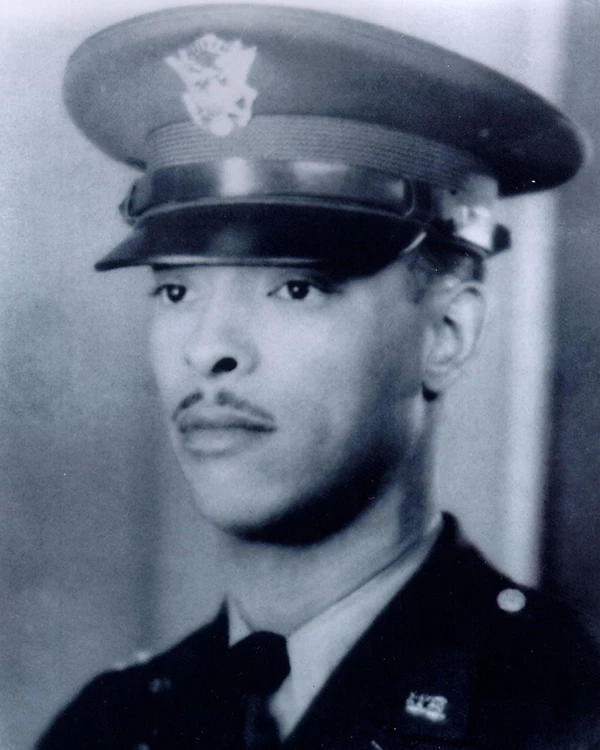

John R. Fox

Public Domain

John Robert Fox was born on May 18, 1915, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the oldest of three children. He originally enrolled at Ohio State University but transferred to Wilberforce University. While at Wilberforce, he participated in the R.O.T.C. program, which Charles Young started in 1894. During Fox’s time at Wilberforce, the R.O.T.C. program was managed by Captain Aaron R. Fisher, a highly decorated World War I veteran. Fox graduated from Wilberforce and was commissioned a second lieutenant on June 13, 1940.

On February 10, 1941, Fox was assigned to the all-Black 366th Infantry stationed at Fort Devens near Ayer, Massachusetts. At Fort Devens he began artillery training in an antitank unit. The 366th Infantry was unique in having all Black officers except for its commander. The Black officers mainly came from Wilberforce and Howard universities. In late spring 1941, Fox reported to Fort Benning, Georgia for training. After finishing training on August 15, 1941, he returned to Massachusetts.

Throughout 1942 and early 1943, Fox and the 366th Infantry were sent to various locations in New England to guard against German sabotage. The military took this task seriously because sabotage attacks had occurred during World War I. In the second half of 1943, the 366th Infantry were sent for training at A.P. Hill Reservation in Virginia and Camp Atterbury in Indiana.

On March 27, 1944, Fox and the rest of the 366th Infantry left Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia for the European Theater, traveling on the USS General William Mitchell. They initially landed in Morocco and traveled by train to Oran, Algeria. On April 29, 1944, they boarded another ship from Oran heading toward Naples, Italy. Upon arriving, the 366th Infantry was broken up into small detachments and assigned support and guard duties.

On November 4, 1944, Fox and the rest of the 366th were assigned to the 92nd Division in the Po Valley in northern Italy. In early December Fox and Cannon Company of the 366th Infantry were attached to the all-Black 598th Field Artillery Battalion (FAB). The 598th FAB was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert. C. Ross. Ross was pleased to have these new soldiers under his command. As he got to know Fox and the others, he appreciated their esprit de corps and expertise.

On December 23, Fox moved to the front lines and took his place in an observation post in the town of Sommocolonia, Italy. He volunteered for the extended four-day Christmas posting. On Christmas Day, German troops snuck into town wearing civilian clothes. By the next morning, the Germans overran the town and began an attack on the U.S. positions. U.S. forces retreated under heavy artillery fire. Lieutenant Fox ordered his other team members to retreat but he stayed in the observation post to observe the German positions.

From his second-floor position Fox called for defensive artillery strikes to try to prevent the German soldiers from advancing. As the German soldiers continued to advance Fox kept calling in artillery strikes closer and closer to his position. At approximately 11 a.m. on December 26, Fox again called for an artillery strike, but this time the coordinates were his own position. The officers with the 598th FAB were hesitant to land artillery on their comrade’s position. Lieutenant Colonel Ross called Fox to confirm the coordinates and acknowledge that Fox was asking for artillery on his position. Lieutenant Fox replied, “Fire It! There’s more of them than there are of us. Give them hell!” The ensuing artillery barrage killed Fox along with more than 100 German soldiers. His sacrifice stalled the German advance and allowed more American soldiers and Italian civilians to retreat to safety. A week later the American forces were able to retake Sommocolonia. Fox’s body was found, surrounded by 100 dead German soldiers. Fox’s remains were returned to his wife, and he was buried in Colebrook Cemetery in Whitman, Massachusetts.

On May 15, 1982, Fox was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In the early 1990s, the Department of Defense began to study the issue of why no African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor during World Wars II. The investigation looked at historical documents including Distinguished Service Cross paperwork. It was determined that Black soldiers had been denied consideration for the Medal of Honor in World War II because of their race. The report put forward a total of seven men who deserved the Medal of Honor for their actions. John R. Fox was one of them. President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor to Fox on January 13, 1997. The award was presented to Fox’s widow, Mrs. Arlene E. Fox.

Lieutenant John R. Fox’s Medal of Honor citation reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty: First Lieutenant John R. Fox distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism at the risk of his own life on 26 December 1944 in the Serchio River Valley Sector, in the vicinity of Sommocolonia, Italy. Lieutenant Fox was a member of Cannon Company, 366th Infantry, 92d Infantry Division, acting as a forward observer, while attached to the 598th Field Artillery Battalion. Christmas Day in the Serchio Valley was spent in positions which had been occupied for some weeks. During Christmas night, there was a gradual influx of enemy soldiers in civilian clothes and by early morning the town was largely in enemy hands. An organized attack by uniformed German formations was launched around 0400 hours, 26 December 1944. Reports were received that the area was being heavily shelled by everything the Germans had, and although most of the U.S. infantry forces withdrew from the town, Lieutenant Fox and members of his observer party remained behind on the second floor of a house, directing defensive fires. Lieutenant Fox reported at 0800 hours that the Germans were in the streets and attacking in strength. He called for artillery fire increasingly close to his own position. He told his battalion commander, “That was just where I wanted it. Bring it in 60 yards!” His commander protested that there was a heavy barrage in the area and the bombardment would be too close. Lieutenant Fox gave his adjustment, requesting that the barrage be fired. The distance was cut in half. The Germans continued to press forward in large numbers, surrounding the position. Lieutenant Fox again called for artillery fire with the commander protesting again, stating, “Fox, that will be on you!” The last communication from Lieutenant Fox was, “Fire It! There’s more of them than there are of us. Give them hell!” The bodies of Lieutenant Fox and his party were found in the vicinity of his position when his position was taken. This action, by Lieutenant Fox, at the cost of his own life, inflicted heavy casualties, causing the deaths of approximately 100 German soldiers, thereby delaying the advance of the enemy until infantry and artillery units could by reorganized to meet the attack. Lieutenant Fox’s extraordinarily valorous actions exemplify the highest traditions of the military service.”