Last updated: June 18, 2015

Person

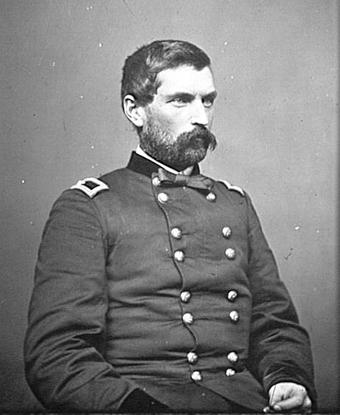

John Gibbon

Library of Congress

From the Peninsula to Maryland: Gibbon's role in the summer of 1862

John Gibbon was born on April 20, 1827 in the Holmesburg neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As a boy Gibbon's father moved the family to Charlotte, North Carolina where he was a slaveholder. Gibbon graduated from West Point in 1847 and served in the Mexican-American War. He was considered an expert at artillery tactics and wrote an artillery manual in 1859 which would be used by both sides during the Civil War.

At the outbreak of the Civil War Gibbon decided to side with the Union despite his southern ties. In 1861 Union Commander Irvin McDowell appointed Gibbon chief of artillery. He would serve in this position until May of 1862 when he was appointed Brigadier General of an infantry brigade then known as King's Wisconsin Brigade.

Gibbon's first major conflict with his brigade was at the Second Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). On August 28, 1862 Union and Confederate forces clashed in Manassas for a second time. The day before the battle, on August 27, Confederate General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's men were able to seize Union General John Pope's supply depot at Manassas Junction. After destroying Manassas Junction, Jackson fell back to the old battlefield of Manassas. Reuniting his troops along Stony Ridge, north of the Warrenton Turnpike, they settled in to await the arrival of Lee and Longstreet.

But before they arrived, Jackson touched off the battle on the afternoon of August 28, when the four brigades of King's Union division moved east along the turnpike to reunite with Pope in Centreville. Jackson ordered his artillery to open fire on the enemy column. Gibbon sent his men to capture the guns, but after advancing up the slope, they realized that they were facing several brigades of Confederate infantry. Despite being outnumbered Gibbon and his brigade continued to fight as the two sides traded volleys only 75 yards apart. By 9:00 P.M. Gibbon broke off the engagement and withdrew to the turnpike in an orderly fashion, the Confederates too exhausted to pursue. The fighting at Brawner Farm had ended in a hideous tactical stalemate. After two more days of fighting the Union forces had been defeated and the

Confederates launched the Maryland Campaign, what would be their last major invasion of the North.

Following the Second Battle of Manassas Gibbons and his men moved on to South Mountain. Days before the conflict there Major General George B. McClellan obtained a copy of Special Order 191 which detailed that Confederate General Robert E. Lee's forces would be divided and vulnerable to attack. Acting quickly, McClellan ordered men to South Mountain where the Union troops could move against the isolated Confederate forces. Fighting erupted on September 14, 1862 in the mountain passes: Crampton's, Turner's, and Fox's Gaps. Gibbons and his brigade were charged with taking Turner's Gap from the Confederates, a task they successfully completed. Upon hearing of the valiant fighting of Gibbon's brigade McClellan commented that "they must be made of iron." From that point forward Gibbon's brigade would be known as The Iron Brigade.

Despite a victory at South Mountain, McClellan failed to crush Lee's remaining forces, allowing the Confederates to reassemble and take the garrison at Harper's Ferry - the stage was set for the Battle of Antietam. On September 16, McClellan confronted Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg, Maryland. At dawn September 17, Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank that began the single bloodiest day in American military history. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's cornfield, where Gibbons' Iron Brigade attacked from the turnpike, pushing back Jackson's men. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. Late in the day, Burnside's corps finally got into action, crossing the stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolling up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside and saving the day. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout the 18th, while removing his wounded south of the river. McClellan did not renew the assaults. After dark, Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw across the Potomac into the Shenandoah Valley.

Gibbon would serve as the commander of the Iron Brigade until November of 1862. His famous brigade would go on to suffer the highest percentage of casualties of any brigade in the war, while Gibbon would go on to command the 2nd Division and the XVII Corps. He would fight at the Battle of Gettysburg, the Chancellorsville Campaign, the Overland Campaign, the Siege of Petersburg, and in the Appomattox Campaign. Gibbon would be one of three commissioners of the Confederate Surrender. Following the war Gibbon stayed in the military and would retire as a Major General in 1891. He passed away five years later at the age of 68.