Last updated: December 27, 2019

Person

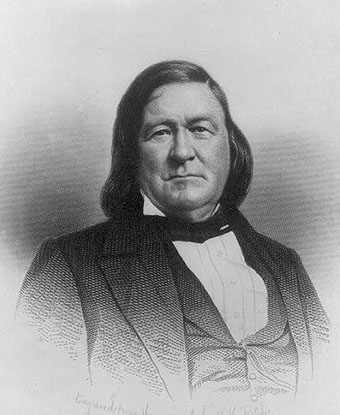

James L. Petigru

Library of Congress

“South Carolina is too small for a republic, but too large for an insane asylum.” - James Louis Petigru of Charleston, South Carolina expressed this unpopular opinion as his native state made the radical decision to secede from the Union in December 1860. Famously the last prominent Unionist in Charleston as the populace embraced secession, Petigru expressed remorse for the death of the Constitution and predicted defeat in the resulting civil war.

Petigru was born near Abbeville on May 10, 1789, the eldest child of William Pettigrew and Louise Gibert. He attended Moses Waddel’s Willington Academy, graduated from South Carolina College in 1809, and taught at Beaufort College while he read law. Admitted to the bar in 182 shortly after changing the spelling of his name, he served as Beaufort District’s solicitor from 1816 to 1822. In 1816 he married Jane Amelia Postell, with whom he had four children.

In 1819 Petigru moved to Charleston where he became James Hamilton’s law partner. Appointed South Carolina attorney general in 1822, he prosecuted all Charleston District civil and criminal cases and represented the state in appeals courts and federal courts. At times, despite his position as the guarantor of state legal authority, he strove to use federal law on race related issues such as enforcement of South Carolina’s Negro Seaman Act that required free black sailors aboard vessels in Charleston Harbor to be jailed.

In 1830 Petigru, a leader of the Unionist faction, resigned as attorney general and was elected to the state House of Representatives. Despite defeat in 1832, he remained a major spokesman for his party until the repeal of nullification in 1833. In 1834, arguing for the plaintiff in McCready v. Hunt, he won a state appeals court decision that the nullifier-imposed test oath for all state officials violated South Carolina’s constitutional ban on such oaths. His dedication to the checks and balances in the Constitution derailed his political career in South Carolina.

Petigru’s prominence after his political career ended derived from his legal career. As adviser to the British Consul Robert Bunch’s campaign to thwart the incarceration of black seamen and when he rescued the free children of George Broad from slavery, he acted both behind the scenes and in court.

Torn between conflicting allegiances to the Constitution and his native South Carolina, Petigru had an unchanging commitment to justice. His loyalty to a constitutionally defined balance of power never wavered, whether it was defining minority rights from majority incursions or checking legislative excess by judicial action. When Charlestonians filled the streets, celebrating the secession of South Carolina with church bells pealing on December 20, 1860, Petigru asked a passerby wearing a blue secession cockade whether there was a fire.

“Mr. Petigru, there is no fire; those are the joy bells ringing in honor of the passage of the Ordinance of Secession.”

“I tell you there is a fire,” responded Petigru; “they have this day set a blazing torch to the temple of constitutional liberty and, please God, we shall have no more peace forever.”

Petigru backed his Unionist sentiment in the courtroom, moving to block the Confederacy’s acquisition of absentee Carolinians’ property and its requirement that lawyers inform against such owners. Although he criticized the Confederate government, Petigru mourned Confederate battlefield losses, especially those in which young South Carolinians fell.

“The universal applause that waits on secessionists and secession has not the slightest tendency to shake my conviction that we are on the road to ruin.”

Petigru died on March 9, 1863 in Charleston, South Carolina. In an impressive tribute, city and state officials as well as Charleston’s Confederate officer corps followed his coffin to St. Michael’s cemetery.