Last updated: February 19, 2024

Person

Horace Loudon

Library of Congress

The tiniest details sometimes yield the biggest stories and questions.

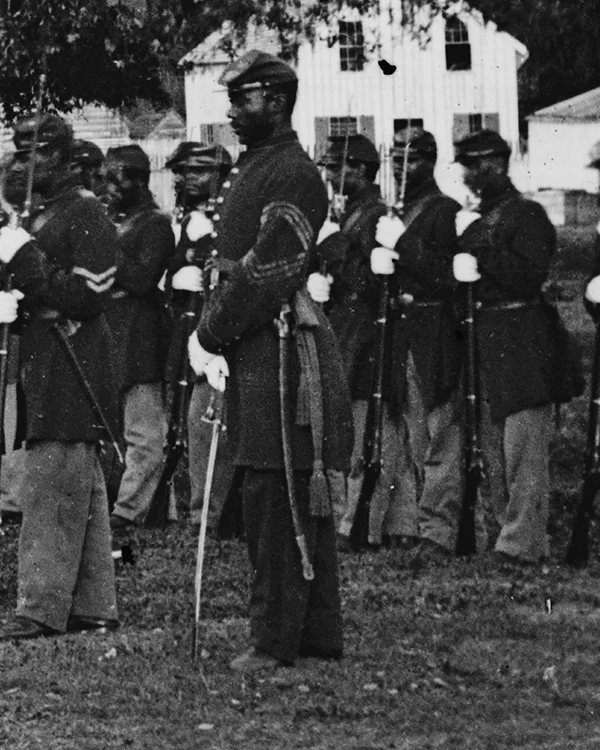

The 29th Connecticut Infantry was stationed in Beaufort, South Carolina for four months in the spring and summer of 1864. The all-Black regiment encamped in the area near the present-day Beaufort Elementary School, and at some point a photographer captured an image of the regiment in formation at the downtown parade ground near the intersection of Bladen Street and King Street. This photo of the 29th Connecticut has become one of the most iconic images taken during the Civil War, and has been in countless exhibits and books as a symbol for Black military service during the conflict. However, one small detail on one of the soldiers allows us to uncover a story.

The soldier at the end of the line appears to be wearing the rank insignia of a Sergeant Major. At any given moment, a Civil War regiment would typically only have one Sergeant Major, who was the highest ranking enlisted man in a unit. This detail allows us to confirm, with some confidence, that the soldier pictured here is probably Sergeant Major Horace N. Loudon.

Loudon was born around 1831 in Milford, Connecticut and was the son of Darius and Maria Loudon. It’s likely that the Loudons had been free for quite some time – perhaps even generations - as Darius can be found living in Milford in both the 1830 and 1840 Census. Maria died in 1855. When Horace was around 21 years old, he chose to be baptized at the 2nd Congregational Church of Milford, where his entire family were longtime members. Incidentally his baptism took place on the 4th of July, 1852 – the same Independence Day forever immortalized by Frederick Douglass in his “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July” speech. By the late 1850s, Horace was working in some capacity as a sailor, as his name appears on a September 1858 register of US-born sailors arriving in New York City. But by the outbreak of the American Civil War, he was working as a shoemaker back in Connecticut. He joined the United States Army in November 1863, and less than six months later, he was standing in the hot sweltering heat of a South Carolina Lowcountry summer.

That summer proved to be his undoing. By late June, Horace Loudon had taken ill with typhoid fever, a bacterial infection associated with unclean drinking water and unsanitary living conditions. He died in the regiment’s hospital in Beaufort on July 6, 1864. Just a few weeks later, the regiment transferred to combat operations in Virginia. Horace Loudon remained behind at Beaufort National Cemetery, where he rests to this day in Section 36, Grave 4109.

In Horace Loudon’s death, we learn more about his life. His service records are somewhat unique in that they list all his belongings that his brother Charles, who also served in the regiment, took possession of. Among Loudon’s belongings were ten volumes of books and a writing slate – Was Horace Loudon teaching his comrades or the people they encountered in Beaufort to read? He also had two books of sheet music along with a violin and a flute. It turns out that Horace Loudon was a musician. It’s not hard to wonder what notes wafted through some of the still standing trees that dot the landscape around where he was encamped. What songs did he enjoy? Did the take requests around the campfire from his comrades while passing the time as they experienced their first summer in the deep south? Did some sailor aboard a small ship anchored on the Beaufort River hear Horace’s violin roll across the water on a starry night and think of home?

What kind of musician would Horace Loudon have been had he survived? Would he have gone back to making shoes in the postwar period, while playing a little music at church? Or would he have pursued his musical passions farther and taken up music as a career? What music didn’t he get to write or play? We’ll never know what Horace Loudon thought about that, although we almost had the opportunity to know.

Among the belongings Horace’s brother collected were two diaries. The whereabouts of these diaries, however, are unknown, and consequently further details of Horace’s story remain untold. What might we know about the experiences of northern Black soldiers during the Civil War had Horace Loudon lived and shared his story in his own words?