Last updated: March 29, 2024

Person

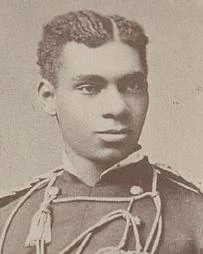

Henry O. Flipper

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Henry Ossian Flipper was born enslaved on March 21, 1856, in Thomasville, Georgia, to Festus and Isabella Flipper. Festus Flipper was a shoemaker and carriage trimmer. Flipper’s parents were enslaved by different men when his father’s enslaver decided to move to Atlanta. Henry’s father used all his savings to successfully petition his enslaver to buy his son and wife so the three could remain together.

After the Civil War, the Flipper family stayed in Atlanta, where Festus set up a shoemaking shop. Education was important to the Flipper family. Henry attended schools for Black students established by the American Missionary Association, a nondenominational group of Christian abolitionists. He attended Atlanta University, an all-Black school also founded by the American Missionary Association, before taking the entrance exam for West Point.

In 1873, Henry Flipper was appointed to West Point by Congressman James Freeman of Georgia. Flipper traveled to West Point and took his entrance exams on May 20, 1873. He was officially accepted into the Corps of Cadets on July 1, 1873. Flipper was the sixth African American to be accepted at West Point. During his first year, Flipper roomed with the first African American to be appointed to West Point, James Webster Smith. Smith wrote Flipper before Flipper arrived at West Point to tell him what to expect upon his arrival. Smith was dismissed from West Point in his senior year after being deemed “deficient” in philosophy. Unlike some white cadets, Smith was denied the opportunity to retake the examination.

After Smith’s dismissal, Flipper had a room to himself for the remainder of his time at West Point. Initially, he found that cadets in his class were friendly. However, the friendly reception turned sour when more cadets were around. Flipper was given the silent treatment throughout his four years at the academy. He wrote, “There was no society for me to enjoy—no friends, male or female, for me to visit, or with whom I could have any social intercourse, so absolute was my isolation.” Flipper found some form of friendship at the academy by talking to the barber, and commissary clerk.

Flipper excelled in engineering, law, French, and Spanish. He was the first African American to graduate from West Point. On June 14, 1877, he received his diploma from General William T. Sherman. The New York Times wrote about the ceremony, “When Mr. Flipper, the colored cadet, stepped forward and received the reward of four years of as hard work and unflinching courage as any young man can be called upon to go through, the crowd of spectators gave him a round of applause.”

Flipper’s first duty station was Fort Sill in Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma. He was assigned to A Troop, Tenth U.S. Cavalry. While at Fort Sill, Flipper took on many tasks. He supervised the building of a road from Fort Sill to Gainesville, Texas. He also supervised the installation of telegraph wires from Fort Elliot to Fort Supply in Indian Territory. His most significant project while at Fort Sill was as lead engineer on surveying and draining stagnant ponds at the fort that were breeding grounds for mosquitos carrying malaria. Because of his success in creating a drainage system, the project was called “Flipper’s Ditch.” In 1977, Flipper’s Ditch was designated a National Historic Landmark and is still in use today.

In June 1880, the Tenth Cavalry was reassigned to Fort Concho, Texas. During Flipper’s time at Fort Concho, he served as a scout and messenger for Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson during the Victorio Campaign. Victorio was a Warm Springs Apache leader who was disgusted by the reservation on which his people were forced to live. Victorio and a group of followers left the reservations and traveled throughout their historical homelands and back and forth across the Mexico-United States border. The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments were given the mission to apprehend Victorio and his group and escort them back to their reservation. After several fierce battles with Victorio throughout New Mexico, Victorio returned to Mexico, where Mexican soldiers killed him in 1881.

On November 29, 1880, Flipper was transferred to Fort Davis, Texas, where he was the quartermaster and acting commissary officer. In July 1881, Flipper noticed $3,791.07 was missing from the commissary trunk. He did not report the theft, because he knew the officers would blame him. Instead, he repaid the money, with the help of local people, in two weeks. On August 13, 1881, Colonel William R. Shafter, commanding officer of Fort Davis, reported he was told by the Chief Commissary Officer of the Department that the funds Flipper sent had never arrived. Colonel Shafter also saw Flipper in town with saddle bags and assumed he was deserting with the money. Two weeks later, Shafter wrote to the adjutant general that Flipper had produced all the money for which he was responsible. Nevertheless, Shafter pushed for a court martial for Flipper.

On September 17, 1881, Flipper was tried before a general court-martial, charged with “embezzling public funds and conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.” During the trial, the prosecution could not produce any evidence that supported the allegations. It demonstrated that Flipper was negligent in the handling of government funds. The court acquitted Flipper on the charge of embezzling public funds. However, he was found guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman, which came with a penalty of dismissal from the Army. In contrast, in two prior situations involving white officers who had been found guilty of embezzlement, neither was dismissed nor dishonored.

Flipper’s case was reviewed the Judge Advocate General and the Secretary of the Army. They both recommended against discharge. President Grover Cleveland, who had to approve the discharge, disregarded their recommendations. Flipper was dishonorably discharged from the Army on June 30, 1882. Flipper later wrote, “Never did a man walk the path of uprightness straighter than I did, but the trap was cunningly laid and I was sacrificed.”

Later in life, Flipper wrote that the white officers’ attitude toward him had started to change when they saw him horseback riding with Mollie Dwyer, the white sister-in-law of Flipper’s commanding officer Captain Nicholas M. Nolan. Although Nolan didn’t seem to mind the friendship, other officers did. Flipper believed this to be the beginning of Shafter’s and other officers’ ill will.

After his dishonorable discharge, Flipper went on to a very successful mining and surveying career in the Southwest and Mexico. He wrote two books about his life. The first was The Colored Cadet at West Point and the other Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper. He also worked for the Department of the Interior working in Alaska and Washington. He petitioned Congress nine times throughout his life to clear his name. Flipper died in Atlanta, Georgia, on April 26, 1940, at the age of 84. He was buried in the family cemetery in Thomasville, Georgia.

In 1976, Flipper family descendants and supporters applied to the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records for a change to his dishonorable discharge. The board concluded the conviction and punishment were “unduly harsh and unjust” and changed his discharge to a good conduct discharge. The Department of the Army issued a Certificate of Honorable Discharge to Henry Flipper dated June 30, 1882, in lieu of his dismissal on the same date. On February 19, 1999, President Bill Clinton pardoned Henry Flipper and reversing the unjust court-martial.