Last updated: September 5, 2023

Person

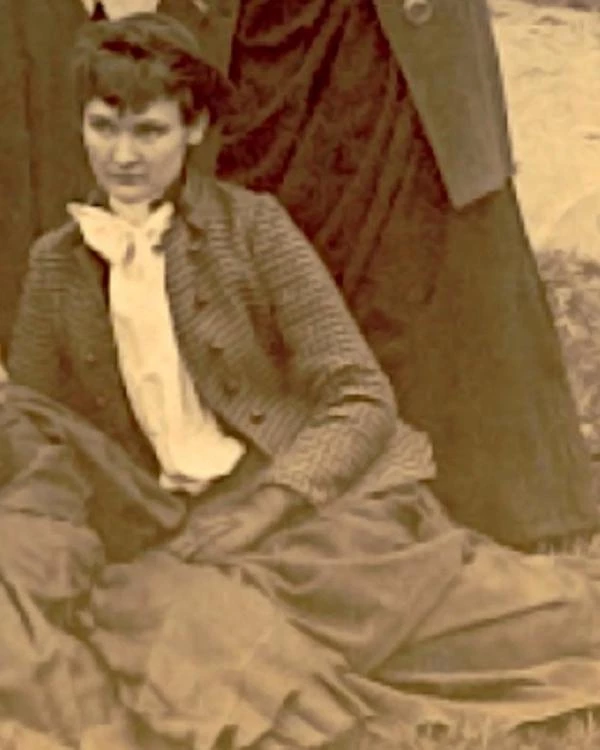

Georgianna (Georgia) Elliott Hasenstab

Gallaudet University Archives, Washington, DC

Georgianna (Georgia) Elliott Hasenstab was a significant person in American Deaf history. She is often recognized primarily as the wife of Philip Hasenstab. Yet, the work she accomplished as a pioneer in the Deaf women's rights movement is noteworthy. She was among the first cohort of women to attend Gallaudet College and she was active in multiple organizations in the city of Chicago. For that reason, Elliott should stand alone as a Deaf historical figure.

Elliott was born in Ohio on May 5, 1867, as the third of five children. Her family moved to rural Illinois when she was young, and the town was later renamed Elliott for her family. The town grew when Elliott's father donated land to build a public school and railroad. At the age of five, Elliott and her family contracted spinal meningitis as part of an epidemic across the central United States. One of her older brothers didn't survive. Elliott's illness resulted in her becoming deaf. Her parents continued to send her to a hearing public school for several years. They later transferred her to the Illinois School for the Deaf, located in Jacksonville, Illinois. It was finally here that she was able to have full access to education and social opportunities with her peers. She attended this residential school from 1876 to 1887, graduating as valedictorian in the spring of 1887.

During the second half of the 1800s, the American Deaf community went through a cultural shift. The first half of the nineteenth century was known as the 'golden age' for the Deaf community. Deaf institutions thrived. The art of sign language (formerly known as manualism) blossomed. But after the Civil War, attitudes towards manualism changed as the eugenics movement and social Darwinism gained ground. The eugenics movement supported the goal of improving society by controlling people's reproduction. Social Darwinism aimed to only select the most "desirable" groups to continue having children. Those who supported eugenics believed that people with disabilities, people of color, low-income communities, and some immigrants were "undesirable." Because of these widespread attitudes, many hearing people believed that Deaf people should integrate into hearing society. To do so, they had to be able to speak. Sign language and Deaf culture came under attack in the late nineteenth century. The Deaf community entered an era where they had to fight to preserve their culture, sign language, and way of life.

Despite being established in 1864, Gallaudet College's doors remained closed to Deaf female students until the 1880s. While Gallaudet accepted a few female students to preparatory school programs on a case-by-case basis, these earlier students did not complete their degrees. It's likely they left due to the unwelcoming environment they found at Gallaudet, or job opportunities that awaited elsewhere. Elliott, aged 19, didn't accept this exclusion. Prior to her senior year of high school in 1886, Elliott wrote a letter to the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf (CAID). This national organization met at various locations every other year, and Gallaudet College president Edward Miner Gallaudet frequently attended. Her letter explained why Gallaudet College should admit young Deaf women. Elliott relied on the language of domesticity to argue for the advancement of Deaf women. The language of domesticity was the belief that, as wives and mothers, women could influence politics and society from their homes. The more educated a woman became, so the thinking went, the better able she was to support the country and its institutions from within the domestic sphere. Elliott also argued that girls excelled in school as much as boys. Elliot's letter received unanimous support at CAID's biennial meeting.

The Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae (WACA) got involved in the coeducation issue a few months after Elliott wrote her letter to CAID. WACA was a hearing association with the mission of advocating for coeducation. The organization believed that Deaf women had a right to a collegiate education. They sent a letter to President Gallaudet, pointing out that Gallaudet College received federal funds. They inquired as to how the federal funds were being managed since Deaf women were being excluded. President Gallaudet then invited exceptional female students to attend Gallaudet College, the catch being that they could only stay for an experimental trial of two years. Students were recommended by their deaf residential schools and six young Deaf women, Elliott among them, were chosen to join Gallaudet's male cohort in the fall of 1887.

Participating in this coeducation experiment was not easy for Elliott and her female peers. They faced ridicule from their male counterparts. They could not attend extracurricular activities unchaperoned. They had to work twice as hard to earn basic respect from the male students and faculty.

One highlight of Elliott's Gallaudet years was her visit with Susan B. Anthony at a reception on January 25, 1888 at the Riggs House hotel in Washington, DC. The Washington Critic newspaper specifically mentioned Elliott's and three other female Gallaudet students' attendance at the reception. The visit with Anthony must have been a success because in February, The Deaf-Mutes' Journal announced that Anthony had invited Elliot to speak at the International Council of Women. The conference was to take place in Washington, DC in March of 1888. Unfortunately, no records have been found that confirm that Elliot accepted the invitation.

The experimental trial was a success. In 1889, Gallaudet College officially opened its doors to Deaf women. Instead of graduating, however, Elliot chose to become a teacher at the Missouri School for the Deaf. While she was working there, she began her courtship with Philip Hasenstab. Philip worked as a teacher at the Illinois School for the Deaf. They had met when she was a high school senior at the school. Their courtship was a long one, lasting five years. During that time, they both worked as teachers at their respective schools. She played a pivotal role in encouraging Philip to follow his calling to become a clergyman. In 1890, he became the first Deaf ordained minister in the history of the Methodist church. Three years later, he left teaching to become a full-time Deaf minister in Chicago.

The Elliott family did not approve of Philip for two primary reasons. His family was Catholic at a time when anti-Catholic prejudice ran high in the United States. Philip had converted to Methodism as an adult but the Elliott family remained suspicious. Additionally, a minister's income was modest. They were afraid that Philip would not be able to provide Elliott with financial security. Despite her family's disapproval, Elliott married Phillip on June 20, 1894. Upon her marriage, Elliott stepped down from teaching. She relocated to Chicago to help her husband with his Deaf ministry, at the Chicago Temple Building in the heart of downtown Chicago.

During their 47-year marriage, Elliott and Philip welcomed four daughters. Elliott was busy as a wife and mother yet she remained involved in the Deaf ministry and social reform organizations. She was able to do this because her mother Anna Elliott lived with the family for 14 years from 1895 to 1909. Anna supported the upbringing of the four Hasenstab girls allowing Elliott to continue her work in the Chicago Deaf community.

In her role as a clergyman's wife, Elliott became known as the "First Lady" of Deaf Methodism. According to letters to Philip, Elliott took pride in her church work. When her husband traveled to preach at other locations, Elliott sometimes took his place in the Chicago pulpit. She wrote her own sermons and shared them on Sundays. This was a bold step for a woman, as they could not yet become ordained ministers or hold official positions in the Methodist church. Elliott's actions reflected a change in the church and showed how women were striving for positions of authority in church communities. In one of her letters to Philip describing the church service in his absence, she wrote:

You may be now wanting to know about the meeting. I shall tell you here first of all, I feel that God was there and blessed the meeting abundantly: His spirit moved it I feel. I think I never preached so enthusiastically as I did yesterday in my life.

Following a sermon she delivered, she wrote to Philip:

I think it really did go all right. Everyone seemed interested and paid good attention. Mr. C – you know, yourself, that he is hard to reach, did not turn his attention away and said afterward that he had enjoyed it all. I was relieved it went all right.

While she worked in the ministry, she also focused on volunteer charitable work outside the church. Elliott worked with the Chicago Ladies' Aid Society. This organization focused on improving the quality of life for poor people in the city. Elliot also helped out with the Epworth League. The league's goal was to nurture the spiritual life and community mindedness of young adults. This kind of work was common for middle-class women in the early 1900s. During the Progressive Era, private citizens often managed relief work in absence of governmental support. This work was especially important as U.S. cities experienced waves of immigration. Elliott was one of many who felt motivated to "improve" society. She likely knew of and was influenced by Jane Addams, famed for her social reform work at Hull House in Chicago.

Elliott worked in the Chicago Deaf ministry and on social reform efforts until her death. She died on July 26th, 1941, at the age of 74, surrounded by family. Her husband Philip continued their work until he died six months later in late December 1941. Community members, including Elliott's daughter Constance, took over the Chicago Deaf ministry. But, to this day, the work of Elliott's life remains unnoticed by the majority of historians. In the words of Proverbs 31 etched in her tombstone, let her own works praise her.

NOTE: When studying Deaf History, there is a significant difference between capitalization of the letter "d" in "Deaf" versus "deaf." "Deaf" identifies a culturally Deaf person or the Deaf culture. Deaf culture describes a set of common values, traditions, and achievements of a group of Deaf people. This can take the form of the nationwide usage of American Sign Language, establishments of Deaf institutions, organizations and clubs, and the celebration of Deafness. On the other hand, "deaf" with a lowercase "d" describes a medical condition, a hearing loss or a disability.

It is important to note that the useage of "Deaf" versus "deaf" was not a concept known or used during Elliott's lifetime. The concept did not exist until the late 1980s. This article uses the 21st-century language of "Deaf" to describe Elliot because she subscribed to the cultural norms, values, and practices of Deaf culture.

This article was written by Lexi Hill, National Council for Preservation Education Intern with the National Park Service Park History Program. 2022.

Acknowledgements: William Ennis, Brian Greenwald, Jeffrey Joeckel, Lu Ann Jones, Jannelle Legg, Turkiya Lowe, Perri Meldon, Kirk VanGilder, Ella Wagner, Roberta Wendel.

Sources:

Baynton, Douglas C. "Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History," In The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard Davis, New York: Routledge, 2013.

Baynton, Douglas C. Forbidden Signs: American Culture and the Campaign Against Sign Language. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Gannon, Jack R., Jane Butler, and Laura-Jean Gilbert. Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 2012.

The Deaf-Mutes' Journal. "College Chronicle." February 16, 1888. The Internet Archive. Accessed September 9, 2022. https://archive.org/details/TheDeaf-mutesJournalfeb.161888

Krafft, Beatrice Elliott Hasenstab. A Goodly Heritage. Columbus, Georgia: Brentwood Christian Press, 1989.

The Washington Critic. "Miss Anthony's Callers. A Delegation of Lady Students from the Deaf Mute College." January 26, 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress. Accessed January 4, 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82000205/1888-01-26/ed-1/seq-1/

Reference:

The Illinois School for the Deaf along with several houses associated with its founding and early development are contributing resources within the Jacksonville Historic District. The nomination form for the historic district discusses the founding of the school and the vital role it played in the growth and development of the city of Jacksonville in general and its West Side in particular. The district and its contributing resources were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 (NRHP 78001178).