Last updated: October 26, 2024

Person

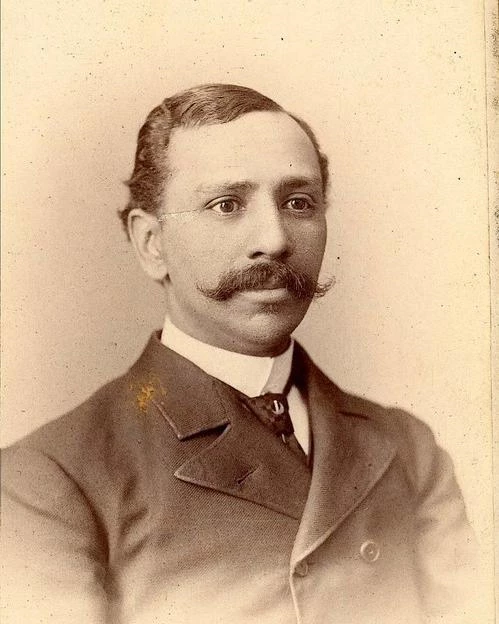

Edward P. McCabe

Kansas State Historical Society

Edward P. McCabe was a pioneering African American politician in the American West, Black town promoter, and important citizen in the early history of Nicodemus. He worked tirelessly throughout his life to create opportunities for African Americans to live and work freely without threats to their civil rights, and the impacts of his work are seen today.

Edward Preston McCabe was born on October 10, 1850 in Troy, New York. During McCabe's childhood, his family lived in several states in the Northeast, and he went to school in Providence, Rhode Island and Bangor, Maine until his father died. Afterward, McCabe began to work to support his family.

McCabe worked as a clerk on Wall Street in New York for the firm Shreve & Kendrick until he moved to Chicago in early 1872, becoming clerk of the Cook County office of the Federal Treasury that same year. There, he completed his legal education and was involved with a club of Black Republican voters. He also befriended Abram T. Hall, an ambitious Black journalist, in Chicago.

In April 1878, Hall and McCabe learned of Nicodemus while in Leavenworth, Kansas. The two had actually intended to go to the new Black colony in Hodgeman County, but Hall heard about John Niles, who was in Leavenworth collecting relief supplies for Nicodemus, and met with him to learn about the town. McCabe and Hall decided to instead accompany Niles back to Nicodemus.

Once in Nicodemus, McCabe quickly became involved in local business and politics, setting up a successful land location business for Black homesteaders with Hall. He was also appointed notary public of the still-unorganized Graham County in August 1878.

During the town’s first couple years, the Nicodemus Town Company had solicited aid to help residents who had few resources. By 1879, many in town, including McCabe, feared that some residents would grow reliant on aid or that some solicitors were keeping aid for themselves. Edward McCabe was among the citizens who decided to officially end aid requests from the colony and published a formal resolution of this that was printed in several newspapers throughout the country.

McCabe and Hall pushed for the organization of Nicodemus as a township before Graham County was formally organized and had a county seat; this resulted in a brief period where all Graham County citizens had to conduct their formal business in Nicodemus.

1880 was a busy year for McCabe. In early April, he attended the Kansas Republican Convention in Leavenworth with Abram T. Hall. Later in April, he was selected along with Zachary Fletcher, Abram T. Hall, and Granville Lewis to be part of the Graham County delegation for the Kansas State Convention of Colored Men. Though the men could not attend this convention, they sent a letter sharing their support. When Graham County was formally organized that year, McCabe was appointed temporary county clerk. In October 1880, he married Sarah Bryant of Clinton, Iowa.

Encouraged to run by Millbrook Times editor Benjamin B. F. Graves, Edward McCabe made history in 1882 when he was elected state auditor of Kansas, making him the highest-elected Black official outside of the American South. While Edward McCabe won by a landslide, his election was not guaranteed. McCabe faced backlash by both Black and white Kansans, partially due to colorism, or discrimination based on skin tone. Some Black Kansans didn’t trust McCabe to champion their interests because he was a lighter-skinned Black man and was never enslaved. At the same time, McCabe’s complexion made him more appealing to some white voters, though racism still impacted other white voters. Many Kansans, though, saw McCabe as a skilled politician and highly devoted to the advancement of Black Americans in the United States, and his record of work in Nicodemus proved that fact.

With his skill and attention to detail, McCabe easily won re-election as state auditor in 1884. However, when McCabe made a bid to run for a third term in 1886, the Kansas Republican party refused to nominate him. This was possibly due both to the party’s dislike of candidates running for third terms and the fact that the Republican party was increasingly alienating its Black members. McCabe’s time as state auditor ended in January 1887.

While McCabe kept his home in Nicodemus and returned there periodically during his time as auditor, he did not return to Nicodemus after 1887, instead living in Topeka for a few years. In Topeka, he worked with Kansas Republican Preston Plumb and the Oklahoma Immigration Association to encourage Black settlement in Oklahoma Territory.

On April 22, 1890, McCabe, along with William L. Eagleson, a well-known Black newspaper editor, and Charles H. Robbins, a white land speculator, established Langston, Oklahoma as an all-Black settlement. McCabe founded the Langston City Herald in October 1890 to not only promote Langston but also encourage Black migration to Oklahoma Territory. With McCabe’s efforts, Langston boomed in its early years, and in 1897, McCabe’s influence helped establish the Colored Agricultural and Normal University. It was later renamed Langston University and is the only HBCU (Historically Black College and University) in Oklahoma.

There was controversy surrounding McCabe’s efforts to encourage Black settlement in Oklahoma Territory. To many, he gave the impression that he wanted to make Oklahoma an all-Black state. This idea was especially unpopular for white Democrats living in Oklahoma Territory and Native Americans who had been forced onto reservations in Indian Territory (the eastern part of modern-day Oklahoma, which was also open for non-Indigenous American settlement). However, McCabe never stated that this was his intention. Much like in Kansas, McCabe also received pushback from some Black Oklahomans who felt he did not represent their interests.

Despite opposition, Edward McCabe became well-known in Oklahoma politics during the 1890s and 1900s. He established a law office in Guthrie, 12 miles from Langston, and in 1890, he was appointed Logan County’s first treasurer and then secretary of the Oklahoma Territorial Assembly. In 1895 he was appointed chief clerk of the Territorial Assembly. From 1897 to 1907, McCabe served as deputy territorial auditor under 4 territorial governors. He lost this position when Oklahoma became a state in 1907 with a Democratic-majority government that did not want people of color in political positions.

Edward McCabe's efforts to improve the lives of African Americans in Oklahoma was not yet done. In 1908, McCabe and four other Black politicians went before the Federal district court to argue that a recently passed Jim Crow law in Oklahoma was unconstitutional. The Separate Coach Law, passed in December 1907, ordered railroads in the state to establish separate railcars and waiting rooms for Black and white citizens. McCabe argued that this law violated the Oklahoma Enabling Act of 1906, which contained a section stating that “There shall be no distinction on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

Unfortunately, the district court ruled against McCabe, claiming that his case wasn’t valid because neither he nor the other filers could prove they had personally experienced discrimination on the railroads due to the law. The district court also claimed that because there were separate facilities for Blacks, and they were not actually excluded from riding on trains, the law did not violate the Enabling Act. McCabe argued that “any separate accommodation is a distinction between the races and is thus a violation," and appealed this case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. In 1914, in the case McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company, the Supreme Court upheld the previous court rulings that McCabe and the others had not been discriminated against and that separate facilities on railroads did not violate their constitutional rights. One of the cases cited in defending this decision was Plessy v. Ferguson, which had famously established the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine.

Besides this court case, McCabe’s life after leaving Oklahoma in 1907 is little-known. Shortly after leaving Oklahoma, he briefly traveled to British Columbia, Canada to investigate starting a Black settlement there before moving back to Chicago. In 1913 and 1914, he was reported to be involved in the Back-to-Africa Movement by working with Ghanaian Alfred C. Sams to bring Black Oklahomans to Ghana. McCabe seems to have moved back to Chicago around 1914 and, after the conclusion of the court case, led a relatively quiet life. He passed away on March 12, 1920, and was buried in Topeka, the funeral attended only by his wife, an undertaker, and a gravedigger.

While Edward P. McCabe died in relative obscurity, the impacts of his influence in African American politics and civil rights are far-reaching. At the time of his election as state auditor, McCabe forced Kansans to look beyond race when electing officials, proving his merit through hard work and skill. His long political career and persistence inspired other African Americans to run for public office and break racial barriers. Throughout his life he continuously promoted equality for African Americans through legislation and political activism. In Nicodemus, he played an important role in the early years of settlement and worked to establish the town’s permanence and self-reliance. Edward McCabe launched his political career in Nicodemus and Graham County, using the experience and respect he gained there to break political barriers for Black Americans in the western United States.

Sources

- "A Black Bolt.” The Daily Oklahoman, August 10, 1898. Newspapers.com.

- Abram Hall to Mrs. Kathryne Henri, September 6, 1937, in Belleau, William J. “Nicodemus Colony of Graham County, Kansas.” Masters thesis, Fort Hays State University, 1943.

- Dann, Martin. “From Sodom to the Promised Land: E. P. McCabe and the Movement for Oklahoma Colonization.” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains XL, no. 3 (Autumn 1974): 370-378. From Sodom to the Promised Land - Kansas Historical Society (kshs.org).

- “Edward P. McCabe,” Find A Grave, accessed October 7, 2024. Edward P. McCabe (1850-1920) - Find a Grave Memorial.

- "E. P. McCabe Former Assistant State Auditor Now Waiter.” Oklahoma State Register, August 31, 1911. Newspapers.com.

- Hinger, Charlotte. Nicodemus: Post-Reconstruction Politics and Racial Justice in Western Kansas. University of Oklahoma Press, 2016.

- “Hon. E. P. McCabe.” The New York Globe, February 17, 1883. Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- “Jim Crow Law Still Holds Good.” Durant Daily Democrat, December 1, 1914. Newspapers.com.

- "Jim Crow Upheld By Court.” The Evening News, September 9, 1908. Newspapers.com.

- McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company, 235 U.S. 151 (S. Ct. 1914). U.S. Reports: McCabe v. A., T., & S.F. RY. Co., 235 U.S. 151 (1914). (loc.gov).

- O’Dell, Larry. “Langston.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed October 7, 2024. Langston | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (okhistory.org).

- “Off for Gold Coast.” The Cashion Independent, February 12, 1914. Newspapers.com.

- Roberson, Jere W. “Edward P. McCabe and the Langston Experiment.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma 51, no. 3 (Autumn 1973): 343-355. Edward P. McCabe and the Langston Experiment - The Gateway to Oklahoma History (okhistory.org).

- Roberson, Jere. “McCabe, Edward P. (1850-1920).” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed October 7, 2024. McCabe, Edward P. | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (okhistory.org)

- “The Sad Ending of Hon. E. P. M’Cabe.” The Topeka Plaindealer, March 19, 1920. Kansas Historical Open Content (1800-2001) on Newspapers.com.