Last updated: May 31, 2022

Person

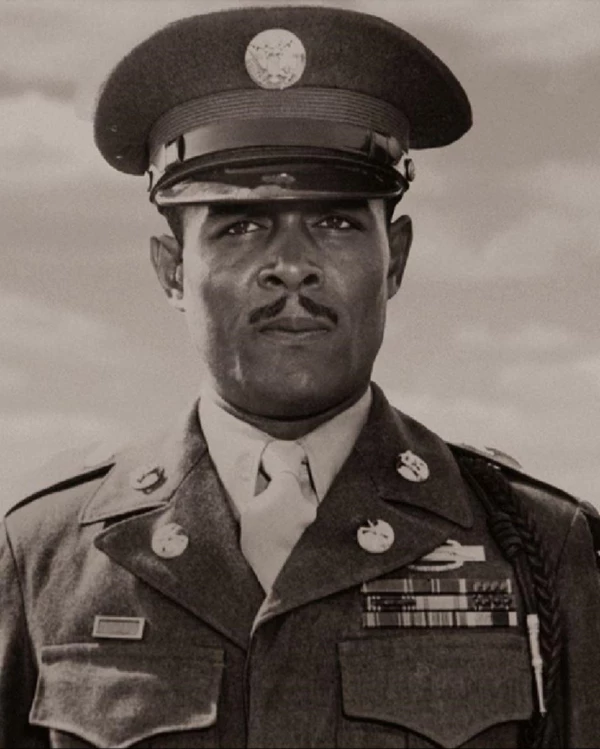

Edward A. Carter, Jr.

U.S. Army

Edward Allen Carter, Jr., was born on May 26, 1916, in Los Angeles, California, to missionary parents. When Carter was nine years old his family moved to Calcutta, India, to start a church. Carter had a difficult relationship with his father and routinely ran away for days at a time. While in Calcutta, Carter became enthralled with the military and envisioned himself serving in the army. During the family’s time in Calcutta, Carter’s mother left them in the care of his father. In 1927, Carter and his family moved to Shanghai, China, on another missionary assignment.

While in Shanghai, Carter attended the Shanghai Military Academy. His father hoped this school would tame Carter’s rebellious nature. During Carter’s time in India and China, he learned to speak Hindi, German, and Mandarin. On January 28, 1932, the Empire of Japan attacked Shanghai in hopes of controlling natural resources in the area. This became known as the “Shanghai Incident.” The Japanese amassed 30 warships and 7,000 troops just outside of Shanghai and bombarded the defenseless International Zone. Carter and his family took refuge in his father’s church.

Carter, moved to action by the continuous bombardment, left the relative safety of the church and ran toward the gunfire. In the streets, he met a member of the Chinese 19th Route Army. Although Carter was only 15, the 19th needed all the men it could get, and Carter took up position in the trenches filling sandbags. As the fighting continued, Carter helped wherever possible. When the vanguard of Japanese Marines started attacking Carter’s position, he took up arms instead of escaping to safety. During the fierce fighting, Carter and his comrades were able to repel the Japanese. After the fighting ended, Carter’s superior officer promoted him to lieutenant and in charge of a section. This was the first time Edward Carter was recognized for his military bravery.

On March 25, 1932, Edward Carter, Sr., arrived at his son’s military camp after looking for him for several weeks. Carter, Sr., met with the general in charge and told him that Carter was only 15 years old. Upon learning that Carter was underage, he was discharged from the military. He returned to his studies at the Shanghai Military Academy with new experience in combat and military tactics. In 1935, Carter left China at the age of 19 and joined the U.S. Merchant Marine, making his way to Los Angeles in 1936.

In January 1937, Carter made his way to Spain via his contacts within the Merchant Marine. He enlisted to fight alongside government forces against the fascists of General Francisco Franco’s army. Franco’s army was backed by the Germans and Italians at the time. Carter was one of 2,800 Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War. He joined the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, made up of mostly anti-fascist Americans fighting alongside the Spanish government.

As the Spanish Civil War progressed, his commanders took note of Carter’s military acumen; he was given increasingly more responsibility on missions. By late March 1939, the government forces were no match for Franco’s German- and Italian-backed military, and Carter and the rest of the Lincoln Brigade escaped to Paris.

By 1940, Carter, now 24 years old, returned to Los Angeles. While in California he met his wife, Mildred Hoover. She helped fill the void created by his mother’s abandonment. On March 27, 1941, they had a son, Edward Carter III. Carter III was nicknamed “Buddha” because of to his size at birth.

Carter enlisted in the U.S. Army on September 26, 1941. He went to Camp Wolters, in Texas, for basic training. At Camp Wolters, he felt racism’s sting. He wrote to his wife, “Conditions here are pretty bad. Only the damned live here in the rotten South. They don’t treat you like soldiers; it’s more like slaves. When this war is over, you’ll see plenty of tough and bitter boys coming home.”

Carter was able to put this aside when it came to military training, at which he excelled. He was proficient with all types of weapons and scored a near-perfect score in marksmanship. Unfortunately, the Army didn’t see the potential in Carter’s weaponry skills, and he was initially assigned to the 3535th Quartermaster Truck Company at Fort Benning, Georgia. Through hard work and determination Carter was promoted to staff sergeant while at Fort Benning.

In the fall of 1944, the 3535th received word they were heading overseas to the European Theater of Operations. They arrived in southern France on November 13, 1944, after a brief stop in England.

Once in France Carter continued to do his job but also kept looking for a way to join a combat unit. He asked for combat duty every day. In December 1944, Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee, deputy commander of U.S. forces in the European theaters of operations, recognized that there were too many African Americans in supply positions but not enough soldiers on the front lines. Lee wanted to change this imbalance by integrating units in Europe on a one-for-one basis. Many generals, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, opposed this one-for-one replacement of white soldiers with Black soldiers.

On December 26, 1944, the official call for Black volunteers in service units to transfer to white combat units received Eisenhower’s approval. The response by men in service units was overwhelming. More than 4,500 African American men applied in the first two months of the program. Unable to accommodate everyone who requested the transfer, the Army accepted 2,500. Carter was accepted but had to relinquish his sergeant stripes and become a private again. He readily agreed, as combat was the reason he enlisted in 1941. Carter graduated from combat training on March 12, 1945, and was assigned to Company D, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division.

On March 23, 1945, Company D pushed across the Rhineland toward Speyer, Germany. Carter and his squad were riding on top of a tank when the vehicle in front of them was hit with a German anti-tank weapon from the direction of a nearby abandoned warehouse. The soldiers immediately leapt off the tank and moved toward the abandoned warehouse. Carter set out over 150 yards from the road to the warehouse trying to ascertain the Germans’ strength. Almost immediately, two of his men were killed and the third was wounded. Carter proceeded alone despite his own wounds. He approached to within 30 yards of the target area and was forced to seek cover, where he stayed for two hours. When an eight-man German squad approached his position, Carter opened fire, killing six and capturing the remaining two. He returned to the American lines with the two German prisoners. Fluent in German, Carter interrogated the prisoners on the way back. He had single-handedly eliminated the last German obstacle to the American advance.

After a month in Luxembourg, Carter recovered from his wounds. He slipped out of the hospital and hitched a ride to the front to be with his unit again. One of the last acts of his Company D commander before he was discharged was to nominate Carter for the Distinguished Service Cross, which Carter received. His commander and others talked about nominating him for the Medal of Honor but were concerned it would not be awarded because of Carter’s race. They thought some recognition was better than none.

Carter returned to Los Angeles after the war. In 1946, Carter re-enlisted in the Army and served at several locations including Fort Lee, Virginia, and Fort Lewis, Washington. He was promoted to the rank of sergeant first class. In 1949, he tried to reenlist again but was denied because of his previous involvement in China and Spain. The army believed he had ties to communism because of his previous service. He appealed the decision numerous times but failed to change the outcome. Rumors of his involvement with the Communist Party resulted in the loss of two jobs and made it more difficult to find other employment. He did, however, eventually find work in the tire industry.

Edward A. Carter, Jr., died on January 30, 1963, in Los Angeles at the age of 46 from lung cancer. He was buried at the Veterans Cemetery in Los Angeles.

In the early 1990s, the Department of Defense began to study the issue of why no African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor during World War II. The investigation looked at historical documents including Distinguished Service Cross paperwork. It was determined that Black soldiers had been denied consideration for the Medal of Honor in World War II because of their race. The report put forward a total of seven men who deserved the Medal of Honor for their actions. Edward A. Carter, Jr., was one of them. President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor to Carter on January 13, 1997. The award was presented to Carter’s oldest son, Edward A. Carter, III. The next day, January 14, Carter was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Staff Sergeant Edward A Carter, Jr.’s Medal of Honor citations reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his own life above and beyond the call of duty in action on 23 March 1945. At approximately 0830 hours, 23 March 1945, near Speyer, Germany, the tank upon which Staff Sergeant Carter was riding received bazooka and small arms fire from the vicinity of a large warehouse to its left front. Staff Sergeant Carter and his squad took cover behind an intervening road bank. Staff Sergeant Carter volunteered to lead a three-man patrol to the warehouse where other unit members noticed the original bazooka fire. From here they were to ascertain the location and strength of the opposing position and advance approximately 150 yards across an open field. Enemy small arms fire covered this field. As the patrol left this covered position, they received intense enemy small arms fire killing one member of the patrol instantly. This caused Staff Sergeant Carter to order the other two members of the patrol to return to the covered position and cover him with rifle fire while he proceeded alone to carry out the mission. The enemy fire killed one of the two soldiers while they were returning to the covered position, and seriously wounded the remaining soldier before he reached the covered position. An enemy machine gun burst wounded Staff Sergeant Carter three times in the left arm as he continued the advance. He continued and received another wound in his left leg that knocked him from his feet. As Staff Sergeant Carter took wound tablets and drank from his canteen, the enemy shot it from his left hand, with the bullet going through his hand. Disregarding these wounds, Staff Sergeant Carter continued the advance by crawling until he was within thirty yards of his objective. The enemy fire became so heavy that Staff Sergeant Carter took cover behind a bank and remained there for approximately two hours. Eight enemy riflemen approached Staff Sergeant Carter, apparently to take him prisoner. Staff Sergeant Carter killed six of the enemy soldiers and captured the remaining two. These two enemy soldiers later gave valuable information concerning the number and disposition of enemy troops. Staff Sergeant Carter refused evacuation until he had given full information about what he had observed and learned from the captured enemy soldiers. This information greatly facilitated the advance on Speyer. Staff Sergeant Carter’s extraordinary heroism was an inspiration to the officers and men of the 7th Army, Infantry Company Number 1 (Provisional) and exemplify the highest traditions of the military service.”