Last updated: January 31, 2024

Person

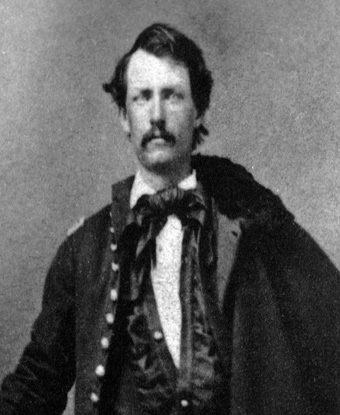

Edward Wynkoop

Denver Public Library Archives

He was the best friend the Cheyenne and Arapaho ever had.

- George Bent

Edward W. Wynkoop was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on June 19, 1836, Ned (as he was known) followed his sister and her husband to the Kansas Territory in 1856. He later moved to the Colorado mining settlements after being appointed sheriff of Arapaho County. In 1861, he met singer and actress Louise Matilda Brown Wakely, whom he married in August.

He arrived in Colorado at a time of conflict with the Indians native to that region - the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Like many Native American tribes, they had been slowly forced from their traditional lands in the Central Plains by settlers surging westward. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 identified lands for them in what is today eastern Colorado. By 1858, a gold rush to the Rocky Mountain area meant a new flood of settlers and miners on their lands, bringing with them new camps and settlements.

A Path Toward Tragedy

In February 1861, Congress created the Colorado territory partially from Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal lands ceded to the US through the Treaty of Fort Wise. This treaty, signed in 1861 by only a handful of Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, including Southern Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle, created the Fort Wise (later Fort Lyon) Reservation. However, most of the Cheyenne and Arapaho rejected the treaty and refused to leave their lands.

Six weeks after the Fort Wise Treaty was signed, the Civil War began. Wynkoop, initially appointed a lieutenant in the 1st Regiment Infantry, Colorado Volunteers, was promoted to major after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Later that year the unit reorganized into a cavalry regiment. In 1864, Wynkoop assumed command of Fort Lyon, on the Santa Fe Trail.

This white man is not here to laugh at us...but...unlike the rest of his race, he comes with confidence in the pledges given by the red man.

- Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle

Tensions between the Cheyenne and Arapaho and the Americans erupted into the Indian War of 1864. Black Kettle and other chiefs sent a letter to Fort Lyon, which stated their desire for peace. Wynkoop, who received the letter, met with these chiefs and headmen at their encampment near the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. Wynkoop impressed Black Kettle, who said: “This white man is not here to laugh at us…but…unlike the rest of his race, he comes with confidence in the pledges given by the red man.”

Wynkoop convinced some chiefs to meet with Territorial Governor (and ex-officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs) John Evans in Denver. During this meeting, the chiefs agreed to report to the Upper Arkansas Agency and place themselves under the protection of the U.S. Army. By late October 1864, approximately 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho were camped along the Big Sandy Creek in compliance with the Army’s instructions. On November 26, Wynkoop left Fort Lyon to report to Fort Riley, Kansas, transferring his command to fellow 1st Regiment Major Scott Anthony.

Sand Creek Massacre and the Aftermath

On the morning of November 29, 1864, Col. John M. Chivington led an attack on the Indian encampment at the Big Sandy Creek. Troops opened fire despite the presence of an American flag and white flag of truce. Soldiers killed many Cheyenne and Arapaho as they tried to flee along the creek bed and mutilated some of their bodies. Soldiers later burned the village. Chivington’s men killed about 220 Cheyenne and Arapaho (mostly women, children and elderly) in what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

The slaughter of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho at Sand Creek led to more fighting on the plains, prompting Congress to demand peace negotiations.

When Wynkoop learned of the attack his shock gave way to rage, and he accused Chivington of murdering friendly Cheyenne and Arapaho. In January 1865, he returned to Fort Lyon to investigate the incident. After visiting the massacre site several months later, he wrote that the site still contained human remains, “three-fourths of them…women and children, among whom many were infants.”

that the site still contained human remains, “three-fourths of them…women and children, among whom many were infants.”

Congressional and military investigations condemned the attack, but Chivington was never held accountable. The slaughter of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho at Sand Creek led to more fighting on the plains, prompting Congress to demand peace negotiations.

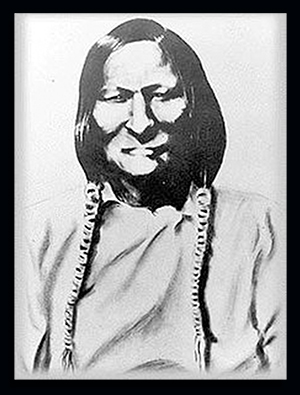

Black Kettle, whose clan was one of several at Sand Creek when the soldiers attacked. This photograph comes from a group picture taken with the other chiefs who met with Colorado territorial governor John Evans at Camp Weld. (Public Domain)

In October 1865, Wynkoop escorted peace commissioners to a meeting with Cheyenne and Arapaho on the Little Arkansas River. The resulting Treaty of the Little Arkansas condemned the Sand Creek massacre, promised compensation to victims’ families, but it also required the tribes to give up lands in the Colorado Territory and relocate to southwestern Kansas and the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). Black Kettle, who survived the horror at Sand Creek, and other chiefs agreed to the terms. Violence erupted when some of the Southern Cheyenne, with no knowledge of this new treaty, returned to find settlers on their land.

Indian Agent

Wynkoop’s service as a soldier and advisor on the Cheyenne and Arapaho, led President Andrew Johnson to appoint him special agent to the two tribes in 1866. Indian Agent Wynkoop established his agency at Fort Larned and worked over the next year to keep peace between settlers and the tribes.

Congress amended the Treaty of the Little Arkansas, eliminating the Indian lands along the Smoky Hill River, but the Cheyenne and Arapaho refused to give up these lands. In April 1867, General Winfield Scott Hancock made matters worse when he destroyed a Cheyenne-Lakota village on the Pawnee Fork.

I most certainly refuse to again be the instrument of murder of innocent women and children.

- Edward Wynkoop

In October 1867, Agent Wynkoop and a peace commission met with the tribes on the Medicine Lodge River. The resulting Treaty of Medicine Lodge established reservations in the Indian Territory. Many Cheyenne, still refusing to give up their home along the Smoky Hill River, refused to sign the treaty. To get their signatures, commissioners agreed to allow the Cheyenne and Arapaho to remain until the buffalo herds disappeared. However, after attacks on white settlements, the Army began a campaign against all the Southern tribes.

Wynkoop advocated the relocation of friendly Indians to Fort Larned, but the Army rejected his plan. Fearing retribution, Black Kettle moved his band of Cheyenne to the Washita River in Indian Territory. U.S. troops attacked and destroyed his village on November 27, 1868, in what would be called the Battle of the Washita. Black Kettle and his wife were killed in the attack.

After Washita, Wynkoop realized that he was powerless to protect the Cheyenne and Arapaho. On November 28, he resigned as Indian Agent. He later wrote: “I most certainly refuse to again be the instrument of murder of innocent women and children.”

Passing

Edward Wynkoop died at the age of 56 of kidney disease in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on September 11, 1891. He is buried in the National Cemetery in Santa Fe. During his remarkable life he witnessed and participated in some of the most pivotal events in the history of the American West. In 1910, George Bent, a Southern Cheyenne Interpreter and Sand Creek Massacre survivor, wrote: “He…was the best friend the Cheyenne and Arapaho ever had.”