Last updated: October 16, 2024

Person

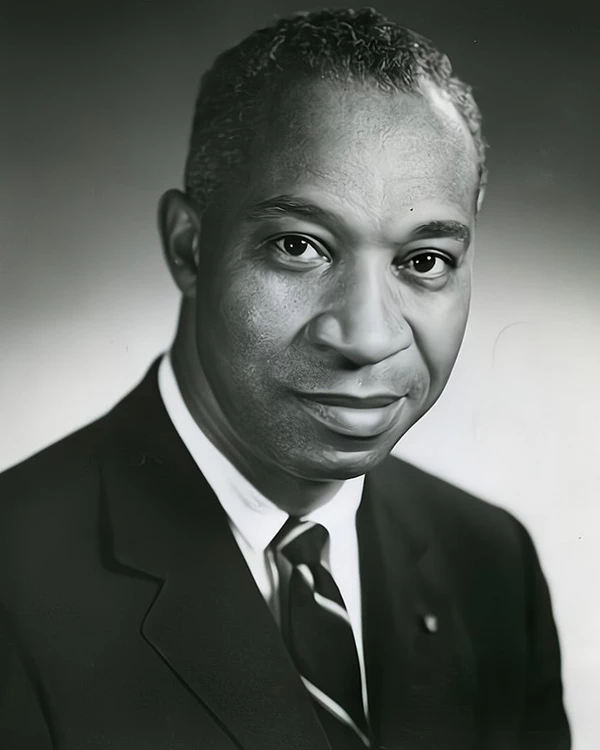

E. Frederic Morrow

U.S. Government Printing Office

Everett Frederic Morrow was born April 20, 1906 in Hackensack, New Jersey. His parents were John Eugene Morrow and Mary Ann Hayes. John E. Morrow was an ordained baptist minister, further working a second job as a library custodian to make ends meet. Mary A. Hayes had previously been a farm worker before becoming a maid. The family continued to live in Hackensack, New Jersey throughout Frederic’s boyhood.

The Morrow family had five children. Frederic was the second child and oldest son of the group. Living in a northern state did not exclude the Morrow family from racial discrimination within the Hackensack community. The family itself came under threat from the Klu Klux Klan when Frederic’s older sister Nellie attempted to become the first black teacher in the county at a white school. However, these moments did not bring despair but instead reinforced the Morrow children’s aspirations to reach higher.

By 1930, Morrow graduated from Bowdoin college and began work as a social worker and vice-chair of the Young Republicans in New Jersey. In 1937, Morrow joined the NAACP as Coordinator of Branches. In this position, he gained a reputation as an eloquent speaker and brave recruiter who ventured deep into the South to energize the black public. Despite this reputation, Morrow would be asked to leave the NAACP in 1950 due to strife within the organization between him and Roy Wilkins. The next two years Frederic found work with CBS as a Public Relations staffer writing CBS program descriptions for newspapers and magazines. In this position, Frederic caught the attention of Dwight D. Esienhower’s 1952 campaign staff.

Morrow’s appointment to the Ike campaign staff in 1952 was a result of Govs. Sherman Adam and Alfred Driscoll’s search for a way for the presidential-candidate to connect to black voters in the U.S. Wanting to be more than a token appointment, Morrow successfully pushed to have responsibilities broader than just outreach to black voters and was given the title and work as “Advisor and Consultant” to the candidate.

In this new position, Frederic traveled thousands of miles with the campaign:giving campaign speeches to black crowds, being asked by Adams how he would respond to Democratic press attacks, and writing memos to campaign staff about what would catch the attention of black voters. Throughout this work, Morrow demonstrated a willingness to support causes he believed in, in spite of putting himself at risk in a high profile position.

Ike’s victory in the 1952 campaign and a promise from Adams led Morrow to believe that a job within the White House awaited him. However, early on in the Eisenhower Administration, no position came. Morrow repeatedly and unsuccessfully reached out to Sherman Adams, now appointed Ike’s Chief of Staff, as well as Maxwell Rabb, Ike’s Cabinet Secretary. Morrow did get a job with the Department of Commerce, not a White House position he was expecting.

Finally, after 2 years, in 1955 Morrow procured a position in the White House staff. Sherman Adam’s came out as a primary influence in running the Eisenhower White House and got Morrow a position on the Special Projects staff of the Executive Office. While Morrow's position was not specifically tied to Civil Rights issues, as the lone black man working in the Eisenhower Administration, he was in a unique position when racial strife occured during the 1950s. Despite the widely held belief that the 1950s were a time of calm and tranquility, racial issues still dominated the era. The Emmett Till murder, the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, the Little Rock Central High School Crissi, and general resistance to school integration all occured during the Eisenhower Administration.

During this period, Morrow was at odds not only with the Eisenhower administration but also himself. He attempted to voice concerns over a perceived lack of action from the administration on Civil Rights. The Civil Rights bill Ike introduced in 1956 was largely gutted by the time it, after reintroduction, reached his desk in 1957. Morrow and other prominent black figures had urged the president not to sign the bill, but ultimately Ike concluded it was better than nothing, ultimately signing the first significant Civil Rights legislation since Reconstruction.

In 1958, Morrow played a key role in setting up a meeting between President Eisenhower and key Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., labor leader A. Philip Randolph, NAACP executive secretary Roy Wilkins, and Lester Granger of the National Urban league. This meeting proved to be a highwater mark of the Eisenhower administration’s outreach to black Americans, and something Morrow himself recalled as “Historic”.

Although Morrow faced constant obstacles during his time with the administration and at times was largely ignored by higher-up staff members, his appointment was nonetheless groundbreaking. Caught between a rock and a hard place in dealing with the Civil Rights leaders pushing for faster action and a political conservative seeking to maintain the status quo, Morrow helped facilitate some of the first steps in breaking down the walls of segregation and white supremacy within the country. Although the 1950s would not see the change Morrow advocated for, this initial breakthrough did make possible the successeses that came over the next decade. Morrow deserves remembrance for his strong character and will to do right in service to the country.