Last updated: April 2, 2020

Person

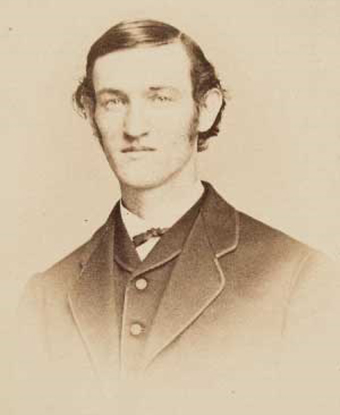

Dorence Atwater

Connecticut State Library

Arguably the most famous prisoner to be held at Andersonville was Dorence Atwater, of the 2nd New York Cavalry. Atwater enlisted early in the war and was captured in the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg. He was sent to Richmond, where he was held on Belle Isle. At Belle Isle he became ill with diarrhea, surviving three trips to the hospital. Finally in January, as a means to save his own life, he accepted a parole to work for the Confederate Army. Although still a prisoner, he worked as a clerk in the office charged with distributing supplies sent from the north to prisoners in the city. From this position he observed extreme cases mismanagement of the Confederate prison bureaucracy. He noted that clothing and blankets sent by the US Sanitary Commission often found their way into the hands of Confederate guards. "Enough clothing was received to have furnished every prisoner with a complete suit and change of under-clothing, blankets, and over-coat, but no prisoner received these articles; if he were furnished with a blouse he must go without a shirt; if with pants he had to go without drawers…" he testified in 1869. He saw one Confederate officer with more than $50,000 that he had taken out of packages sent to prisoners by the families.

Atwater was transferred from Richmond to Andersonville in late February 1864, where he arrived on March 1. In May he became ill again with chronic diarrhea and was admitted to the hospital, which at the time of his admission was still located inside the prison stockade. Remembering the lessons learned in Richmond, he approached Dr. Isaiah White about accepting a parole to work in the hospital as a clerk. He was paroled June 15 and was one of several prisoners charged with maintaining the death register. In late August he took action, and began to secretly copy the death list, largely out of a belief that the Confederate army at Camp Sumter would not turn over the main copy at the end of the war.

Atwater was transferred from Andersonville in February 1865, smuggling his copy of the burial list out with him. He was paroled at the end of the month and was home in Connecticut by mid March 1865. He notified Federal officials of the burial record in his possession, and an expedition was planned was to Andersonville to mark the graves at the prison. While this expedition was being planned, Atwater contacted Clara Barton, offering to assist her with her work notifying the families of missing soldiers. In late July and early August 1865 both Atwater and Barton accompanied the army's expedition to mark and establish Andersonville National Cemetery, and the two spent much of their time going through burial records and writing letters to families of the dead.

Atwater, eager to publish the list, took his copy back from the army at the end of the expedition. He was charged with larceny in a court martial and sentenced to prison. After a few months he was released and went to work with Barton in her Missing Soldiers Office. In 1866, with Barton's assistance, the New York Tribune published Atwater's Andersonville Death Register, bringing Atwater a great deal of public notoriety. He toured the country with Barton lecturing on Andersonville to raise money for the Missing Soldiers Office before joining the State Department as a consul in the 1870s. First stationed in the Seychelle Islands, Atwater eventually settled in Tahiti, where he became a respected businessman and married a member of the royal family. A monument was erected in Atwater's honor in his hometown of Terryville, Connecticut in 1907, and he died in San Francisco in 1910. He was buried in a royal ceremony in Tahiti.

Atwater was one of the most important enlisted soldiers of the Civil War. Around half of all Civil War dead are today marked in unknown or unmarked graves, and the rate is higher in most southern prisons. However, thanks to the work of Atwater and the other paroled clerks to maintain accurate records, and his courage to secretly copy and sneak the list out at great personal risk, around ninety five percent of the prisoner graves at Andersonville are marked.