Last updated: May 30, 2023

Person

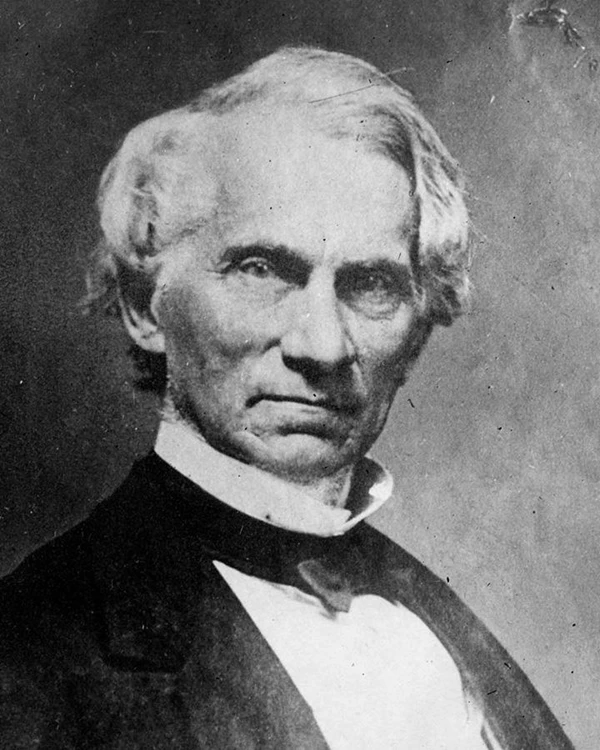

Christopher Memminger at Rock Hill in Flat Rock, NC

Christopher Gustav Memminger was born on January 9, 1803, in present-day Stuttgart-Vaihingen, Germany. His father died when he was an infant. His mother Eberhardina emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina with her parents and son. Memminger's mother died of yellow fever when he was four years old. His grandparents then placed Memminger in the Orphan’s House of Charleston. At age 11 he was adopted by Thomas Bennett, a well-known lawyer and the future Governor of South Carolina. At 13 years old Memminger attended South Carolina College and graduated in 1825. Today, South Carolina College is the University of South Carolina. Afterward, he returned to Charleston to begin a law career working for Mr. Bennett. From 1836 - 1859 Memminger served in the South Carolina House of Representatives. He pushed for reform in public schools, and in 1854, Memminger's reforms created a program of graded schools in Charleston (which only served White children).

Memminger in Flat Rock

There are many manmade features at Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. The original construction of buildings took place under the ownership of Christopher Memminger.

The mountain community of Flat Rock, North Carolina drew Meminger's interest in the 1830s. By that time other wealthy Charlestonians began building summer homes in the town. He purchased a large property in 1838 and named it “Rock Hill” for the granite outcroppings near the home. Many features of the site today originate during Memminger's ownership. Such features include the large white house, surrounding buildings, the lake, dams, and rock walls. Two structures, known today as the Swedish House and Wash House, functioned as quarters for enslaved people. The site we see today is a product of wealth gained through chattel slavery. Memminger was an enslaver in North and South Carolina. Rock Hill's iconic structures were built with both hired and enslaved labor.

Memminger and Slavery

As a lawyer in Charleston, Memminger worked to assist clients trafficking enslaved persons. He also managed many transactions involving people he enslaved as well. At Rock Hill in Flat Rock, he owned as many as 24 enslaved people (including children), while he lived there. Some had specialized skills as carpenters, nursemaids, and butlers. Many records list a butler named Mr. Robert. Mr. Robert prepared Rock Hill ahead of time for the Meminger's later arrival. Ledgers often list "servants" for unnamed enslaved people. Language like "servants" instead of "slaves" softened the violent reality of chattel slavery. Few "servants" were named in records, and even fewer last names made it onto paper.

Memminger and Politics

Before the Civil War, Memminger did not support secession from the U.S., but he did after Lincoln’s election. He joined the Secession Convention of South Carolina. Later, he helped write the Provisional Constitution of the Confederate States. In 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis made Memminger the Secretary of Treasury. The job was daunting. U.S. blockades stopped the export of cotton and rice, the Confederacy's main income. Memminger finally increased taxes to support the war effort, but it was not enough. By 1864, Memminger realized he could not save the Confederacy’s finances. He resigned in July 1864 and retreated to Rock Hill. After the war ended, he resumed his law career in Charleston. Memminger also invested in the phosphate industry. He continued to work in school reform as a member of the Charleston Public School Board. Later, Memminger helped reorganize South Carolina College into the University of South Carolina. He continued to promote separate schools for White and Black children.

Memminger defended the institution of chattel slavery and Black oppression throughout his life. He lived through the time of chattel slavery, Reconstruction, and Post-Reconstruction. He was re-elected to the South Carolina legislature in 1877 based on his previous experience in politics and White supremacist views. He and fellow legislators passed "Black Codes" in 1865, that reinforced racial structures in Post-Civil War South Carolina. Black Codes oppressed Black Americans and forced them to work as a cheap labor force. In a letter to President Andrew Johnson, Memminger wrote that “black people needed white guidance, similar to a master and apprentice relationship, and that they were incapable of political participation or understanding of law.” Former Confederates benefitted from laws that restored White slaveholders as Southern society elites. He died at the age of 85 in Charleston (1888) and is buried at St. John in the Wilderness Episcopal Church in Flat Rock.