Last updated: April 3, 2021

Person

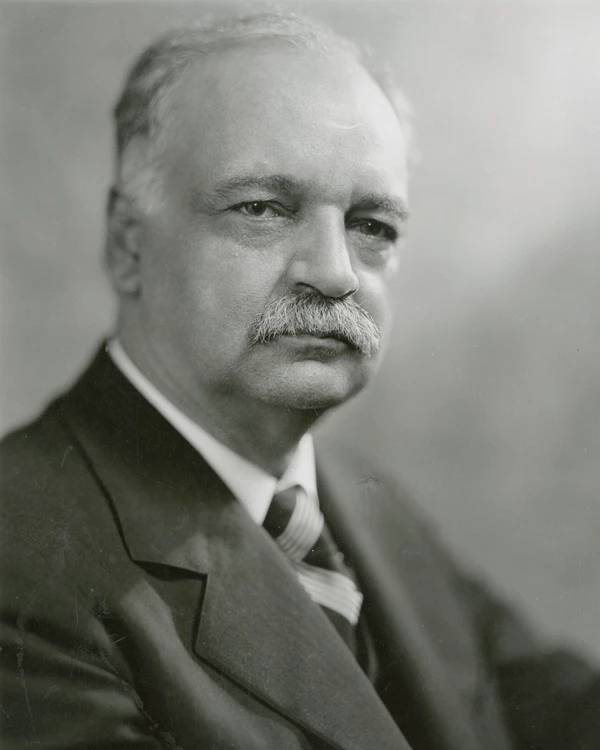

Charles Curtis

National Archives & Records Administration

"… one-eighth Kaw Indian and a one-hundred per cent Republican."

Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis was Herbert Hoover's vice president, and the only person with significant Native American heritage to ever hold executive office in the United States.

Topeka to Washington, D.C.

Curtis was born in Kansas Territory in 1860, a year before it became a state. Through his mother, Ellen Papin, he was an enrolled member of the Kaw Tribe. He was three-eighths Native American— Kaw, Osage, and Potawatomi— and five-eighths European, mostly French, Welch and Scottish.

Curtis grew up on the Kaw reservation in north Topeka. He spoke Kaw and French, the languages of his mother’s family. Ellen died when Charles was only three. He continued to live with his maternal grandparents on the reservation after her death. Later, when the reservation moved from Kansas to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma), Curtis reenrolled with the Kaw Nation and moved with his maternal grandparents.

When it came time for high school, Curtis moved back to Kansas and attended Topeka High School while living with his paternal grandparents. Curtis's father had been in and out of his life, but both sets of grandparents influenced him and helped raise him. He grew up with a foot in each culture.

Curtis was an accomplished jockey, but both his grandmothers encouraged him to pursue other goals. He studied law and became a respected lawyer in Topeka. As a young attorney, Curtis had frequent interaction with Herbert Hoover's uncle, Laban J. Miles, a former agent to, and longtime advocate for, the Osage Nation.

In 1884 Curtis married Annie Elizabeth Baird (1860–1924). The couple had three children: Permelia Jeannette Curtis (1886–1955), Henry "Harry" King Curtis (1890–1946), and Leona Virginia Curtis (1892–1965).

By his late twenties Curtis entered politics. At 32 years old he won election to Washington, D.C. as the Representative from Kansas's 4th district. The ambitious young representative quickly rose to prominence in the Republican Party. A strong believer in assimilation, he worked extensively on Indian affairs. Curtis liked to use himself as an example of an American Indian success story. He played up his heritage in Washington, wearing headdresses and displaying objects from Kaw culture in his offices. He began to set his sights on the presidency, working towards this goal for years and closely with President Warren Harding’s administration in the early 1920s.

Curtis & Hoover

President Herbert Hoover and his vice president were not close. Curtis, for his part, wasn't fond of Hoover either. At the 1928 Republican convention, Curtis spoke openly against Hoover's nomination as candidate for President, while quietly working to promote himself as a compromise choice. Curtis was suspicious of Hoover's work for both Republican and Democratic administrations. Hoover handily won the 1928 nomination. The ticket needed a man from an agricultural state to bring in the farmers who did not like Hoover, so the party nominated Curtis for vice president.

Curtis had a reputation as a jovial man with long experience and many connections in Congress, but Hoover largely ignored him and did not consult Curtis at all on legislation. Hoover relegated Curtis to presiding over the Senate and left him with no power inside the White House. By 1932 Curtis was barely able to win renomination for Vice President at the party convention, despite Hoover taking the presidential nomination again almost unanimously.

After leaving office in 1933, Curtis stayed in Washington to practice law again. He died less than three years later at age 76.