Last updated: March 12, 2025

Person

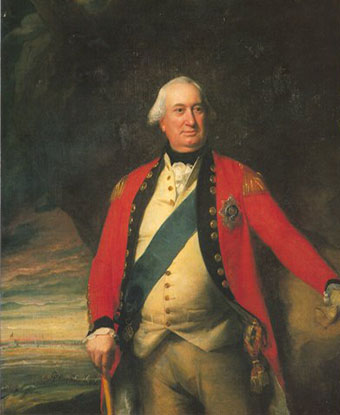

Charles Cornwallis

University of Cambridge

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess and 2nd Earl Cornwallis, served as a general in the British army during the American Revolution. Cornwallis held commands throughout the the war, serving in campaigns in New York, Philadelphia, and notably commanding the southern theater in the field after Clinton's depature in June 1780. Best known for his surrender at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, which effectively ended hostilities and led to peace negotiations between Great Britain and the United States, Lord Cornwallis's postwar career demonstrated the resilience and power of the British Empire. Despite losing thirteen of their American colonies, Great Britiain emerged from the American Revolution with the foundation to build a new, more profitable empire from her victories in India. Cornwallis oversaw this expansion of British power, serving as Governor-General of India from 1786 to 1793 and again in 1805.

Military Pedigree

Cornwallis was the most aristocratic of the British commanders in America. Born in Grosvenor Square in London, he was the sixth child and oldest son of Charles, first earl Cornwallis, and Elizabeth Townshend. In his early twenties, he succeeded to the title and became a member of the House of Lords. His later advancement in the army owed a great deal to his family's status and connections. His family had a long military tradition as well: his uncle, Lieutenant General Edward Cornwallis, and his brother, Admiral William Cornwallis, both had notable careers. Cornwallis received a formal education at Eton College and briefly attended Clare College, Cambridge University. A lieutenant colonel at the age of twenty-three, a privy councillor at the age of thirty, Cornwallis's career enjoyed great success before the American war.In 1757, he obtained leave from the army to travel to Europe to attend a military academy in Turin, Italy. At the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, Cornwallis tried and failed to join his regiment in Germany. He, however, did secure a place on Lord Granby's staff as an aide-de-camp. Cornwallis was present at the battle of Minden when Lord George Germain, later Secretary of State for America in Lord North's cabinet, was disgraced and replaced by Granby. In 1761, Cornwallis became a regimental commander and served with distinction in Germany at the battle of Vellinghausen; the following year, he saw action at Wilhelmsthal and Lutterberg. An experienced veteran of European warfare before his arrival in America, Cornwallis proved a worthy foe for the Continental army. Cornwallis's opposition to British policies that triggered American unrest like the Stamp Act, which he voted against, did not prevent him from volunteering for service in America in 1775. Before his departure to America on February 10, 1776, Cornwallis was promoted to the rank of major general. As colonel of the 33rd Regiment, he sailed with his men from Cork, Ireland in February 1776 to reinforce General Henry Clinton's southern expedition.

Southern Expedition & New York Campaign

During the southern expedition, Cornwallis observed the quarrels between Clinton and Commodore Sir Peter Parker, the naval commander. Unfortunately, Cornwallis left no recorded thoughts for posterity on the mismanaged campaign. After the attack on Charleston, South Carolina was abandoned, following the British defeat at the Battle of Sullivan's Island, Cornwallis and Clinton left to join Sir William Howe in the conquest of New York. The British capture of New York proved to be their biggest victory of the war, involving the most soldiers and sailors. After arriving on Staten Island in August 1776, Cornwallis participated in the British army's advance as they drove Washington's army successively out of Long Island, Manhattan, and finally New Jersey. Cornwallis commanded the reserve wing when Howe defeated Washington at the battle of Long Island. In the final stages of the battle, Cornwallis led the vanguard of Clinton's successful flanking maneuver through Jamaica Pass, defeating a patriot counteroffensive.Cornwallis exposed himself to mortal danger, leading his men visibly on the battlefields. Cornwallis played a role in the British landing and rout of patriot defenders at Kip's Bay when the British landed on Manhattan on September 15. In the early morning of November 20, he commanded the British detachment sent across the Hudson River to capture Fort Lee on the Jersey Heights. Unable to score a victory over the Americans as Washington's army had abandoned the fort, Cornwallis captured the fort and many supplies.

Throughout late November and December 1776, Cornwallis pursued Washington's army across New Jersey. On December 1, he failed in his boast of "bagging the fox", Washington, as he stopped on the banks of the Raritan River in obedience to Howe’s orders to hold position. Retrospectively, this decision can be viewed as one of the greatest mistakes of the war as Washington’s army was at its weakest point and still managed to escape Cornwallis’s larger force. The British, believing the campaign season was over, established their winter quarters throughout New York and New Jersey as Cornwallis prepared to depart for London. Hearing of Washington's surprise attack on the Hessian garrison at Trenton, Cornwallis again took to the field and rode fifty miles to organize a British response. Commanding eight thousand men, Cornwallis's men engaged Washington's army on January 2, 1777 in the Battle of Second Trenton, or the Battle of Assunpink Creek. At the conclusion of the day's engagement, Cornwallis expected to defeat Washington's army the following morning, satisfied their backs were to the Delaware River and they could not evade defeat. Washington and his army, however, escaped under cover of darkness and defeated a British rearguard at Princeton.

British Capture Philadelphia

After the defeat at Princeton, Cornwallis spent the winter months in London before returning to America for the spring campaign. He was instrumental in the British victory at Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and the capture of Philadelphia two weeks later. At the Battle of Brandywine, Cornwallis performed the engagement’s decisive maneuver when he led eight thousands troops in a flanking attack that split the Continental army’s line, striking the forces of patriot Maj. Gen. John Sullivan. A few weeks later, Cornwallis took advantage of Howe's feint towards Reading, which Washington's army moved to counter, and marched into the city of Philadelphia without firing a shot. However, these victories were marred by the crushing defeat and surrender of General John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga, New York on October 17, 1777. As the campaign season ended, Cornwallis again departed America for England. Cornwallis always remained loyal to Howe and acted as a supporting witness for him during a parliamentary inquiry into Saratoga.

Southern Campaign

Shortly after his return to America, Cornwallis traveled to South Carolina in the spring of 1780. By this time, the British had shifted their military efforts to the south. Promoted to lieutenant general and appointed second in command to Sir Henry Clinton in America, he joined Clinton as the British besieged Charleston and, despite their initial amicable meeting, the two quickly developed a poor relationship that affected future communications. On May 12, 1780 the two generals celebrated the surrender of the Continental army and the city of Charleston, which proved to be the greatest British victory of the war. After this victory, Clinton returned to New York and left Cornwallis with about eight thousand troops and the task of securing South Carolina for the British. Cornwallis’s southern campaign started with the spectacular victory over General Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden on August 16. The British outmatched the army under Gates, which consisted in large part of militia, who broke and ran. This victory eliminated organized resistance by the Continental army in the southern theater for several months as it took some time for Gates’s replacement, General Nathanael Greene, to improve the situation. After the victory at Camden, Cornwallis set out to pacify the countryside, a task that proved difficult given stubborn resistance by patriot militia, incensed by Clinton's proclamation demanding fealty to the British crown.The British based their southern campaign on the idea that loyalists outnumbered patriots in the south and would flock to the royal standard. While loyalists did support British operations in the south, their numbers were never as high as the British government had hoped and been led to believe. The anticipated support of allied Cherokee and Creek Indians proved disappointing as well and only further alienated southern frontiersmen against the British. He separated his forces in order to target pockets of patriot resistance and control more of the southern interior and backcountry. After his subordinate commanders, Major Patrick Ferguson and Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, were both defeated at the battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens respectively, Cornwallis had the option to retreat to fight a defensive war in South Carolina or undoing the damage of Kings Mountain by resuming his offensive in North Carolina.

With the situation growing dire, Cornwallis sought to strike one last blow to destroy Greene’s growing army. He had his army destroy their baggage and began a wild chase of their foe to the Dan River. Cornwallis eventually caught Greene, and the two armies fought the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781. The British won the battle, but at a very heavy cost and the Continentals under Greene managed an orderly escape.

Campaign in Virginia & Siege of Yorktown

Despite the losses his army suffered, Cornwallis decided to leave Wilmington, North Carolina and advanced into the poorly defended and heavily populated colony of Virginia. Meanwhile Greene’s Continental Army stayed in the Carolinas, gradually pushing the British back to coastal enclaves at Charleston and Wilmington. Cornwallis threw Virginia into chaos as he captured Richmond and Charlottesville. His feared commander of the British Legion, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton led a raid on Monticello, the personal estate of Governor Thomas Jefferson, in an effort to capture the author of the Declaration of Independence. The British Army was still in a vulnerable situation after these successes, andClinton ordered Cornwallis to establish a naval post on the Chesapeake. Clinton had grown nervous with Cornwallis’s expeditions and ordered his troops back to New York.The Marquis de Lafayette and General Anthony Wayne, commanding Continentals in Virginia, shadowed and harrassed Cornwallis's march to Yorktown while a large French fleet under Admiral de Grasse approached the coast. The combined forces of the Continental Army and the French army under Washington and Rochambeau saw an opportunity and moved to trap the British army at Yorktown. Cornwallis expected support from Clinton but was unaware of the presence of the superior French fleet, which won the Battle of the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781, gaining control of the sea. Unaware of the circumstances, Cornwallis slowly fortified Yorktown throughout August before discovering on September 8th that Washington and the French were marching south.

The allied forces began to bisiege the British at Yorktown on September 28, 1781. Cornwallis withdrew his outer defenses closer to the town of Yorktown as he faced a superior foe. The French and Americans initiated a steady bombardment of artillery fire and slowly dug their siege lines closer, eventually capturing two British redoubts that were critical for British outer defenses. Cornwallis, left with no other option but to surrender, sent a flag of truce to negotiate the surrender of his army on October 17. Cornwallis sought to surrender with the traditional honors of war, but Washington demanded harsh terms as they had denied the Americans those honors at the surrender of Charleston in May 1780. The Articles of Surrender were signed on October 19, 1781. Cornwallis, unable to stomach the embarassment, did not attend the surrender ceremony, citing illness. Brig. Gen. Charles O'Hara led the British army onto the surrender field and attempted to hand his sword to the French General Rochambeau, who refused. He next offered it to Washington, who refused and pointed to General Benjamin Lincoln. Cornwallis’s loss at Yorktown led to the cessation of major hostilities. Peace negotiations between the British and Americans resulted in the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which recognized the independence of the United States.

Postwar Career

Cornwallis enjoyed the most successful postwar career of any of the British generals of the American Revolution. From New York, Cornwallis sailed to Portsmouth, England, joined by Benedict Arnold. Despite his surrender at Yorktown, the public greeted him as a hero upon his return to England. In 1786, King George III created Cornwallis a Knight of the Garter. Cornwallis largely ignored criticisms leveled by Clinton in Clinton's pamphlet, denouncing Cornwallis for the British defeat at Yorktown. Tarleton's criticisms of Cornwallis in his memoir of 1787, however, hurt the former commander.In 1786, Cornwallis was appointed to the position of governor general of Bengal and commander in chief of British forces in India. Commanding an army of twenty thousand men, larger than his southern army during the Revolution, he defeated forty thousand troops of Tipu Sultan during the Third Mysore War (1790 - 92). This campaign helped pave the way for British control of south India. Cornwallis implemented racial segregation of offices, with white imperial officials gradually gaining exclusive hold of senior appointments. He also worked to create an efficient imperial bureaucracy. Following his success in India, Cornwallis was appointed lord lieutenant and commander in chief of Ireland in 1798.

Cornwallis, as a lieutenant general, led his troops into battle in Ireland, defeating a French invasion force of eleven hundred men commanded by General Joseph Humbert. While walking in Dublin in 1799, he was the victim of an attempted assassination when a disguised sentry fired at him and fled. Cornwallis returned to India in 1805 and died shortly after his arrival. The House of Commons voted a memorial and statue to his memory in St. Paul's Cathedral. The British inhabitants of Calcutta raised a public subscription to pay for a mausoleum on a bluff over the River Ganges for Cornwallis's remains. The inscription reads: "This monument, raised by the British inhabitants of Calcutta, attests their sense of those virtues which will live in the remembrance of grateful millions, long after it shall have mouldered in the dust."

Sources

Bowers, Tyler. "Charles Cornwallis." George Washington's Mount Vernon. Accessed March 2025.

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of the American Revolution. New York: David Longworth, 1802.

O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson. The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire. United States: Yale University Press, 2013.

Rosenberg, Chaim M. Losing America, Conquering India: Lord Cornwallis and the Remaking of the British Empire. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2017.

Saberton, Ian, ed. The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War. East Sussex: Naval & Military Press, 2010.

Tarleton, Banastre. A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America. London: T. Cadell, 1787. Reprint, New York Times & Arno Press, 1968.