MENU

|

National Park Service Uniforms Ironing Out the Wrinkles 1920-1932 |

Number 3 |

|

| |

|

|

|

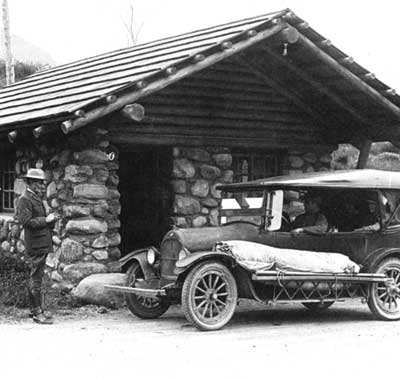

Fountain Station YNP 1923. Left: John Delmar,

Right: John W. Delmar. Here is an example of the numerous two

generation families of rangers in national parks. The Delmars served at

Yellowstone. NPSHPC - YELL/1 and NPSHPC - YELL/2

| |

Frank Pinkley, c. 1925. National Archives RG 79-G-40P-1 |

Horace Albright and Washington Lewis were appointed a committee to work up recommendations for revising the Service's uniform regulations in 1923. They began by sending out a questionnaire to all the park superintendents. A summary of the answers can be found in Appendix B. Most of those who commented liked the present uniform, except for the pinch-back of the coat, but felt that it could be made of a lighter and better material. There was much comment about the collar insignia with suggestions and some sketches of possible changes. While a few thought that there should be more differentiation between the officers and the rangers, most agreed with Frank M. "Boss" Pinkley, custodian at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument:

"It seems to me that our organization is so small, and will always remain small, there is no reason for a lot of distinctive grades. The visitor in the Park only knows of three general grades: the Superintendent, the Ranger, and all others connected with the Service. Give the Superintendent shoulder straps and a round badge; the Ranger his shield badge, and all others plain uniforms. Twenty-four hours after your visitor lands in your park he knows how to pick out a Ranger if he wants one, or the Superintendent if he wants to lodge a complaint. If the exception arises and he needs to meet some other department head, let him ask the first person in uniform and he will get detailed directions. This is from the visitor's standpoint. From the Service standpoint too much distinction is not wanted. We are all engaged in serving the people who come to us. The ranger who is filling his job up to the brim is entitled to just as much respect as the Superintendent who is doing the same. If you say the Superintendent is carrying the greater responsibility, my reply is that he is getting paid more money for doing it and that settles that. The Officer might need a better grade of cloth when at work in his office than the Ranger will need when at work in the field, but I see no reason for not allowing the other members of the force to wear as good cloth as they care to buy when it comes to public functions."

North entrance checking station, 1923, Yellowstone National Park. This is the way the park kept track of who and how many tourists visited the park. NPSHPC - YELL/1743 |

Pinkley also thought, along with others, that the collar and sleeve insignia were not necessary. Of the latter he wrote:

"The force in a Park is so small that each employee knows the status of all others. The visitor doesn't care whether the Chief Ranger wears a pair of crossed cactuses with a shovel rampant, while the Ranger wears only one cactus and two shovels and the temporary ranger wears a pick couchant; what the visitor wants is a ranger, and he promptly picks him out by his shield-shaped badge and goes and pours his woes in his ears. The fact that it is the third assistant ranger he is talking to means nothing in his young life.

Washington Bartlett "Dusty" Lewis, 1926, superintendent, Yosemite National Park. Lewis was one of the prime movers in uniforming the National Park Service rangers. NPSHPC - YOSE/#RL-9429 |

One item Pinkley brought up that had not been touched on by others was the matter of uniforms for the women in the Service:

"I have never heard anything about uniforms for the women of the National Park Service. I meant to interject this into the discussion at Yosemite, but just at that moment someone waved a gray shirt in front of Col. White [John R. White, superintendent of Sequoia National Park], and when he stopped for breath twenty minutes later the Chairman changed the subject. Let me ask here why the women are not entitled to distinctive uniforms, and service stripes and so on."

After reviewing the responses to the questionnaires, Lewis and Albright checked on the availability of lighter materials for uniforms. Gabardine was inspected but discarded in favor of whipcord. The Sigmund Eisner Company was contacted and a deal was arranged to supply the Service with 125 to 150 uniforms.

Lewis submitted new regulations to Director Mather on February 9, 1923. They contained several changes from the 1921 regulations. All field personnel were now required to purchase and wear regulation National Park Service uniforms. Forestry green whipcord was now optional for officer and ranger uniforms. Superintendents and custodians were the only officers other than the director and assistant director authorized to wear badges (as Mather had previously decreed); theirs were to be of the round form, nickel plated. Coats of all uniformed personnel were to always be fully buttoned. The $5.00 badge deposit was incorporated in the regulations, which admonished employees: "Badges are not to be sold or otherwise disposed of. They are issued to show authority and should not be allowed to fall into the hands of unauthorized persons." The new regulations were approved and distributed to all superintendents and custodians.

There was some discontent among the superintendents about the lack of uniformity in the gray color of the shirt, as indicated by Pinkley's remark about Superintendent White. Some thought that the Service should arrange for a sole-source supplier to ensure color uniformity. When White inquired about this, he was informed that the Service could not contract for anything that it would not be paying for but that the employees might be able to make such an arrangement themselves. [16]

Top

Top

Last Modified: Thurs, Dec 14 2000 9:30:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/workman3/vol3c8.htm

![]()