|

Parks, Politics, and the People

|

|

|

Chapter 6: The CCC: Accomplishments and Demise For the National Park Service I reported in part as follows:

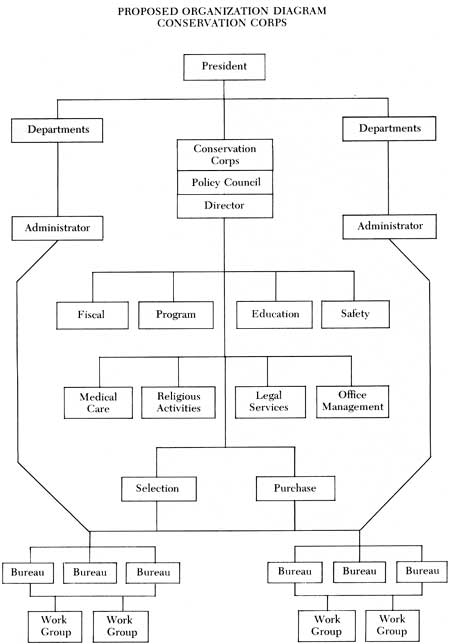

Because of the accomplishments and the success of the original CCC, I felt that a similar type of organization should be authorized on a permanent basis, and I enumerated my reasons as follows: (1) There was in the thirties, and still is, a need to give nationwide attention to the conservation of our natural resources. The natural resources are so vital to our existence and progress that it seems reasonable to give them continual attention and protection. (2) The general type of program as planned and executed by the CCC was well received by all. Perhaps one of the greatest accomplishments of the civilian Conservation Corps was that it made the people of this country aware of the value of an active conservation program. (3) The CCC not only taught the youth of our nation in a very practical way the meaning and value of our natural resources but helped to strengthen the nation's human resources. (4) The CCC program was looked on by many as a relief program rather than a conservation program, and that view was justified to a certain extent. A good conservation program can do much toward the relief of the unemployed, although its main and most important objective is conservation. (5) The CCC program brought together many subdivisions of government in such a way as to help them realize that the protection of natural resources was a problem common to all. (6) Learning how to handle heavy equipment proved to be of great value to the boys when the time came for them to leave camp. Men with experience in handling and repairing equipment were in demand by private business concerns and government agencies, including the armed services. (7) Standard and attractive CCC uniforms created and maintained a fine organization spirit. (8) The two-year limit of service impressed upon the boys that they must progress and that the CCC was a place to learn how to work and to prepare themselves for better jobs. (9) Work outdoors, regular hours, and plenty of wholesome food did wonders for the health of the boys at one of the most critical growing periods of their lives. (10) Camp life and recreation programs taught cooperation and team play to a very high degree. Brigadier General George P. Tyner, a representative of the War Department on the CCC Advisory Council, stated before a committee of Congress that he felt the training of the boys in the CCC camps was equal to 75 per cent of the type of training required of the soldiers in the army. I concluded by saying that the CCC had been deficient in several respects and that, if a similar organization was to be established, those faults should first be carefully examined. I attributed the CCC's deficiencies and lack of effectiveness to the following: (1) The CCC director's office superimposed controls over the departments' management and development of federal properties. General policies and controls were necessary for a unified CCC program, but they must not interfere with the primary functions of the departments. The director of the CCC assumed more and more administrative control over the camp programs, and towards the end he was interfering with the responsibilities of the departments in the management of their properties. This interference became worse with the addition of the administrative controls of the Federal Security Agency. (2) While the relationship between the army and the technical services in the field and in Washington was very good, many administrative officers felt that simplification and consolidation of control in the camps would remove excessive overhead. For instance, the use of two finance agencies—the Treasury Department for regular functions and the Finance Office of the War Department for the CCC—caused unnecessary additional work for the technical agencies. While the army finance officer did an excellent job, two procedures and two different sets of records and forms were required on each area where CCC and regular funds were being spent, frequently on the same general work project. (3) Many work projects could have been undertaken more economically with smaller camps. The two-hundred-man camp was considered the smallest unit that could be used to justify the dual overhead cost of the army and technical agency. But the financial loss in an overmanned work project more than offsets the increased man-unit overhead cost of a smaller camp. Further, if more than two hundred men were needed, the addition had to be a multiple of the two-hundred-man unit, and by this rigid procedure the man-unit overhead cost could not be reduced much below the two-hundred-man unit camp. (4) The trend to build up a classroom type of educational program in the camps with impractical (and unpopular) academic courses confused the understanding of the purposes of the corps. Practically everybody believed it to be reasonable and desirable to teach the boys reading and writing; first aid and safety measures; and how to advance themselves in the type of work to which they seemed best adapted. Many could not understand, however, why the boys were urged and even pressured to take a foreign language, or other regular classroom courses, after a hard day's work in the field. While the CCC operation had faults, none was serious enough to nullify the good it did for the boys and the country. Minor adjustments in organization and policy would provide an adequate solution. I strongly believe that the United States should establish an organization similar to the Civilian Conservation Corps on a permanent basis and that such an organization should be a joint enterprise of the federal departments and agencies that now administer and protect the natural resources of the nation. The natural resources that make up the livable environment of the world do not conform to political or jurisdictional boundary lines, and an environmental conservation program must therefore be a joint interagency program. The main objectives of the proposed corps should be: (1) Development and protection of the natural resources of the country for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations; (2) Teaching the workers and others the necessity and the importance of proper use of the natural resources; (3) The coordination and integration of a nationally planned program through a uniform and respected work organization that does not interfere with the existing objectives and responsibilities of the various member agencies; and (4) Cooperation with and aid to the states and their political subdivisions and the owners of private holdings in matters of conservation. Under this proposed system the president of the United States would appoint the director. Each of the departments or independent agencies using the resources of the corps would appoint two members to the policy council. One of these members would be the department's administrator of the corps activities within the department he represented. The other member would be the representative of the head of the department and the senior high policy representative. Each department would have one vote. The two appointees from each department and the director appointed by the president would constitute the policy council of the corps. The policy and regulations governing the operation of the corps would, in all cases, be made or approved by the policy council. The director would be the chairman of the council, It would take a majority vote of the council, plus one additional vote, to approve regulations or to establish policy.

The director would have direct charge of certain functions of the corps. These functions would be decided upon and approved by the policy council. Generally speaking, these functions would be only those that are common to all operating agencies, that would help to unify the corps, and that would be more economically handled by central organization. It would also be the director's responsibility, acting through the administrators of the departments or agencies, to see that all policies and regulations of the corps are properly and promptly carried out. Some of the functions that might logically be placed in the director's office are: Fiscal. It would be necessary to assemble in one place the budget requirements for all activities of the corps for presentation to the Bureau of Management and Budget and the Congress. After the funds have been appropriated it would be necessary to allot them to the departments and keep certain limited financial records. Program. The operating agencies would, from time to time, submit their requirements for camps or men, and these requests would have to be assembled and presented to the council through the director for approval. Records of the decisions would have to be kept, and orders would have to be issued to the departments or agencies to carry into effect the decisions of the council. Education. A basic education program should be adopted. Such a program would be limited in the camps to job training and the teaching of reading and writing. It would be necessary to have, in a central location, a division that would see that a unified program was maintained for the corps and that would make reports and recommendations for the policy council's consideration. Purchase. It would be economical for one office to purchase and warehouse items that are required for the member departments or agencies, and to ship out, on requisition, items such as clothing, shoes, bedding, cooking and camp equipment, and certain staple foods. It also would be the duty of this division to collect and recondition such items as clothing and shoes wherever practical and to warehouse them for reissuing. The bureaus would have full control of all phases of the work projects in their areas and would be held directly responsible for adherence to the policies and regulations of the corps. Appointment of personnel would be in accordance with civil service and department procedures. In selection of personnel under this procedure, special consideration should be given to their qualifications as leaders of young men. Development and protection programs would be undertaken either by camps or by small groups of men, not less than ten or more than forty. In cases where small groups of men were supplied, the bureau would have to meet all basic responsibilities of the corps—supervision, health care, housing, and so forth. Camps would range in size from a fifty-man unit up, in multiples of fifty. A superintendent would be in charge of a camp and all its activities. This proposed system of organization has several advantages. The departments and agencies most concerned with the development, protection, and use of natural resources would have a definite hand in formulating the policies affecting the work program on the areas under their administrative control. The director, as the president's appointee, could make such reports to the president as were found necessary. The value of a uniform organization of young men working on conservation projects would be maintained. Setting up a strong administrative office within each department would provide the controls necessary to insure adherence to the regulations that make the corps a uniform organization. The bureaus would have the full responsibility for all of the activities of the corps on the areas under their administrative jurisdiction, including camp management, which they did not have under CCC. This arrangement would eliminate the conflict that existed under the old setup between the army and the technical services as to camp location, campground development, division and release of men, and the like. It should also reduce the general overhead costs and permit the use of smaller camps at a reasonable man-month cost. Moreover, it would make possible the use of small groups of men without the establishment of camps, where the area to which they were assigned had the facilities available to take care of them. Besides these general advantages, such an organization would be flexible and would fit into changing and varying conditions. The complete text of my final report to the secretary of the interior of the department's Civilian Conservation Corps program for the period March, 1933, to June, 1943, was inserted in the Congressional Record by Senator Henry M. ("Scoop") Jackson, of Washington, in support of a bill (S. 1595) that he introduced in the Ninety-second Congress proposing to establish a permanent organization along the lines of the CCC (Congressional Record, 92d Congress, 1st sess., April 20, 1971, vol. 117, #54, pp. S5155-5165). Other similar bills have been introduced from time to time, but Senator Jackson has been one of the strongest advocates of this proposal. A lot of the good things said about the CCC have been said best by some of the people who were associated with it in one capacity or another. In 1954, during a period when an effort was being made outside of government to form an organization to sponsor legislation for the establishment of a permanent conservation corps organization, a former CCC staff man—an educational adviser—wrote as follows:

It is regrettable that legislation establishing a permanent conservation corps was not enacted while the success of the CCC and its great accomplishments were foremost in people's minds. Many believed that if the cold war had not followed World War II the CCC would have been reestablished and on a permanent basis. Several similar work programs have been considered. In fact, in 1972 a test program was authorized by Congress and instituted by the Departments of Interior and Agriculture. This trial period proved very successful, and in 1975 Congress considered legislation to enlarge and extend the program for a five-year period. Representative Lloyd Meeds, of Washington, asked me to come up and start the hearing off with a recommendation made by the Department of the Interior. Although I did not have enough time to study the bill in detail, I accepted the invitation and made remarks in connection with the value of the CCC program as I knew it. A Forest Service man spoke after me at the hearing. The next day in a Washington, D.C., newspaper I read that he was there to oppose the bill on behalf of the administration because the White House believed that it would be inflationary and that it was up to private enterprise to hire the unemployed, not the government. The main trouble with most of the programs that have been considered and tried so far is that everyone wants to make a complete study of overhead, classification of personnel, and what not, before even putting anybody to work. One of the beauties of the 1933 operation was that the laws went through with a purpose in mind, and it was left to the administrators to carry out that purpose. It is true that some of the laws passed in the first hundred days of the New Deal were found unconstitutional and had to be changed or done away with, hut nevertheless for the periods they were in effect many served a very good purpose. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

| ||

Parks, Politics, and the People ©1980, University of Oklahama Press wirth2/chap6c.htm — 21-Sep-2004 Copyright © 1980 University of Oklahoma Press, returned to the author in 1984. Offset rights University of Oklahoma Press. Material from this edition may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the heir(s) of the Conrad L. Wirth estate and the University of Oklahoma Press. | ||