|

Whtie Sands

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FOUR: GLOBAL WAR AT WHITE SANDS,

1940-1945 (continued)

The American Airlines stunt typified the aggressive promotional activities of the Alamogordo business community, from which had come Tom Charles and the monument itself. In 1940 the chamber initiated another campaign to upgrade the status of White Sands from a monument to a more-prestigious (and better-funded) national park. Nationwide publicity had resulted from a visit to the dunes in December 1939 by Ernie Pyle, the Pulitzer prize-winning journalist and Albuquerque resident whose praise for White Sands, and for Johnwill Faris' hospitality, reached millions of readers. In March 1940, the chamber petitioned U.S. Representative John J. Dempsey to upgrade the facilities at White Sands, especially its need for more drinking water. Joseph Bursey, state tourism director, and local columnists echoed these sentiments, and circulated a rumor that the New Mexico congressional delegation would introduce a bill to change the status of White Sands. Faris himself became excited at this prospect, as he hoped that the move would elevate his position (and salary). The SWNM superintendent believed that this rumor was nothing more than standard fare from zealous local boosters, but Hugh Miller did praise Faris and his monument staff by saying: "You have a most promising area both from the standpoint of its merit as a national attraction and from the standpoint of revenue which is becoming an increasing factor of influence with the Bureau of the Budget." [6]

Johnwill Faris realized soon thereafter that the "park status" stories had ensnared him, as Tom Charles had warned during the 1938 WPA scandals. At the close of the New Deal, a conservative Congress had reduced spending on the many public works projects that had assisted White Sands with its infrastructure. This also reduced political involvement in the inner workings of the NPS, although conditions in southern New Mexico bucked national trends. The state WPA office inventoried the labor force at White Sands in 1940, finding that two-thirds of the contract workers were Hispanic. These employees stayed on the payroll longer than the federal limit of eighteen months, prompting Hillory Tolson, director of the NPS' Santa Fe regional office, to warn J.J. Connelly, state WPA administrator, that the park service would run out of money for its White Sands construction well before the close of the 1940 fiscal year. [7]

Political interference of a more direct nature involved the persistence of fired WPA carpenter Michael Reardon to regain his job and his reputation. Reardon employed an Albuquerque lawyer, Robert H. LaFollette, who pressed the park service to reinvestigate the WPA "scandal." LaFollette (not identified as a relative of the progressive Wisconsin senator of the same name) believed that White Sands officials had reduced WPA wages arbitrarily, and that Reardon had been punished for testifying to that effect before a federal grand jury. The park service, mindful of Reardon's connections to New Mexican politicians Dennis Chavez and John Dempsey, sent Reardon's case file to Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, who concurred in the judgment of regional NPS officials. [8]

Because of the uniqueness of the New Mexico New Deal, Johnwill Faris had to move cautiously in the election year of 1940. The following June he wrote in his monthly report of the appointment of John Dempsey as undersecretary of the Interior. Dempsey had run against Chavez in the 1940 Democratic primary race for U.S. Senator, only to be defeated. President Roosevelt then named Dempsey to the Interior post, prompting Faris to say: "The Honorable John Dempsey knows well the problems of the west and we can be assured of an understanding representative in Mr. Dempsey." This was unfortunately not the story that Faris conveyed privately to regional director Miller. J.L. Lawson, former owner of the controversial Dog Canyon property, had defied the Otero County Democratic party by supporting Dempsey, and Faris feared a reprisal against White Sands. "Tom Charles is bitterly opposed to Dempsey," said Faris, "and not one but many rumors have it that Dempsey will get Tom out of the picture at White Sands[,] etc." Lawson himself greeted Faris on an Alamogordo street by asking "how I liked my new boss [Dempsey]." The custodian told Miller that he should "look behind the scene" if problems arose at the monument, as people said: "You never can tell about Lawson." [9]

Doubts concerning the sentiments of Interior officials towards White Sands could not deter Johnwill Faris or the regional office in the months preceding U.S. entry into World War II. The lack of staff bothered NPS supervisors, who devoted considerable time to writing an interpretative manual for use in ranger talks. Natt Dodge came to White Sands to observe the operations and maintenance of the museum, which had opened in June 1940. "Undependable electric current," plus a lack of heat in winter, limited the museum's appeal to visitors in its first year, as did the incomplete design of the museum exhibit cases. Then the heavy summer travel brought dozens of visitors at one time through the museum, with no staff available to explain the monument's features. By August 1941, the NPS could send additional employees to the dunes, but had no funds to address the structural problems of electricity and heat. [10]

The strain upon the monument's facilities also reflected problems old and new: the environmental conditions in the arid Tularosa basin, and the experimental nature of New Deal policy. The ecology of the dunes affected the water supply, whose high salt content corroded pipes and clogged drains several years after construction. High winds damaged lines from Alamogordo built to deliver telephone service, requiring park staff to check the transmission network each time they traveled into town. Newton Drury, director of the park service, noted in his inspection tour in May 1941 that the blowing gypsum not only covered the roads (causing high maintenance costs), but also abraded the engines and chassis of NPS vehicles used in clearing the highway. Most interesting, however, was the deterioration of the adobe walls and buildings. Their style reflected the New Deal's sense of place and historical distinctiveness. Yet the mud construction cracked and chipped during heavy rains, and required annual maintenance for plastering that the NPS had not included in its designs. Then late in 1941 the monument received ten inches of rain within a ten-day span, inundating roads, damaging the adobe structures yet again, and restricting visitor travel to the dunes. [11]

To meet these needs, NPS officials at first turned to their benefactors, the New Deal agencies that had constructed facilities at White Sands. Despite nationwide curtailment of such programs as the WPA, CCC, and other organizations, New Mexico' s political leaders had managed to retain WPA personnel at the dunes. Johnwill Faris had continued to use the federal work crews to keep his park open, with Jesus Armijo devoting all his time to collecting admission fees at the monument entrance. As late as April 29, 1940, President Roosevelt had authorized expenditure of $57,500 for non-construction maintenance at White Sands. These crews built Spanish-colonial furniture for the headquarters, cleared the roads, painted signs, and planted cacti and other native vegetation around the visitors center. [12]

Dependence upon funds other than the NPS appropriation caught White Sands off-guard less than two months after FDR's proclamation, as word reached Custodian Faris of the termination of all Recreation Demonstration Projects at the close of the 1940 fiscal year (June 30). SWNM superintendent Miller came to the dunes in early September, and noted the pressing need for improvement of facilities and services. Predicting that White Sands "may readily receive 100,000 bona fide visitors next year," Miller feared that the decline in federal support would "create an unfavorable impression of the Park Service as a whole." Upon consultation with Custodian Faris, the superintendent agreed that White Sands' only hope was establishment of a CCC camp (one of the few remaining New Deal labor programs) to fulfill duties that the NPS had never been able to accomplish. [13]

While the superintendent saw logistical and procedural obstacles, Hugh Miller also recognized White Sands' predicament: high visitation, elaborate facility construction, and limited financial resources. The U.S. Forest Service had a CCC camp outside of El Paso (the Ascarate County Park), which needed more work to remain viable. The cost of shipping workers and materials the one hundred miles to White Sands made creation of a new camp at Alamogordo more feasible, as the lack of potable water at the dunes restricted the housing of two-hundred plus workers. Regardless of the problems, said Miller to the regional office, "we have an urgent situation on our hands at White Sands." He further encouraged Johnwill Faris to submit a twelve-month work plan to the CCC at once. [14]

The custodian's response indicated the extent to which White Sands depended upon New Deal largesse for its operations. Johnwill Faris devised a program to employ 200 workers for one year, housing them on ten acres of land outside of Alamogordo that city leaders would donate to the CCC. These crews could engage over a dozen projects, none of which included original construction. The menu ranged from housing to roads to landscaping to museum lighting. One interesting feature was Faris' wish to devote 12,500 "man-days" (the number of days times workers) to remove five miles of the old clay-plated entrance road. Built in 1933 by the CWA, the road had been replaced by an asphalt route, but visitors sometimes followed the old path by mistake. Faris also wanted 12,500 man-days to convert Garton Lake to the wildlife refuge first intended in its purchase. These activities, concluded Faris, "will enable us to become an area well balanced and prepared to handle the number of visitors that is apparently destined to come our way." The custodian then acknowledged the consequences of failure to meet these needs by not gaining a CCC camp: "Without the work we may be years rounding out a similar outlined program without embarrassment and virtual disgrace to our Service." [15]

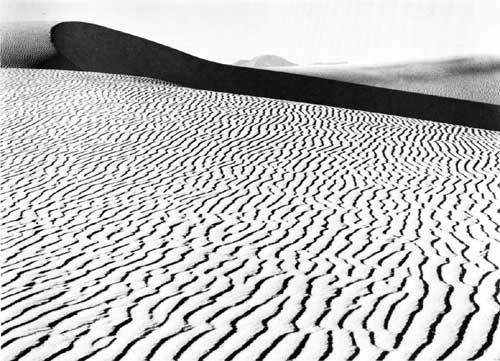

Figure 29. White Sands, New Mexico. Laura Gilpin (1943).

(Courtesy Laura Gilpin Collection. Copyright 1981. Negative No. 2600.2. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth TX.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

whsa/adhi/adhi4a.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001