| War in the Pacific: The First Year |

A Guide to

the War in the Pacific |

|

|

War in the Pacific: The Pacific Offensive Changing Tides of War: Allied Pacific Counteroffensives As both hemispheres were embroiled in war, Allied political and military leaders sought strategy and tactics and new forms of weaponry designed to check and turn back any further advances by the Axis Powers. It was in this year, 1943, that the long and hotly debated theory of strategic bombing took a deadly form, as Air Marshal Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris digested and honed the lessons of the first 1,000-plane night raid made in June 1942 on Koln [Cologne]. The strategic bombing of Japan, protected by thousands of miles of ocean and "impenetrable island fortresses," would have to wait until 1944. Although the European Theater "theoretically" took precedence over the Pacific, the United States in the first four months of 1942 committed more resources to the Pacific than Europe because the situation was so critical in Southeast Asia and the Malay barrier. The situation then changed and American, New Zealand, and Australian forces in the Southwest Pacific led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, and initially by Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghromley and then by Vice Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey, and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Area, boldly seized the initiative that resulted in an island-by-island counteroffensive that would lead to the Philippines and Okinawa.

MacArthur's South Pacific Command was confronted by a formidable task in seizing bases in the rugged mountains of New Britain, New Ireland, New Guinea, and the Solomons as primary objectives. Most of these large mountainous islands were clad in rain forest. The final goal was New Britain and Rabaul. Within Cartwheel, Operation One (Chronicle) called for the occupation of Kiriwina and Woodlark islands; Operation Two (Postern) was the capture of the Salamaua, Lae, and Finschhafen areas; and Operation Three (Dexterity) the occupation of Western New Britain and Keita and the neutralization of Buka. MacArthur launched Cartwheel on July 1, 1943, when Allied forces made unopposed landings on Woodlark and Kiriwina islands off the northeast coast of New Guinea.

The significance of the battle for Guadalcanal that ended with the Japanese evacuation of the starving and fever-racked remnants of their forces from the "Island of Death" on February 9, 1943, was underscored in the weeks and months that followed. United States and New Zealand aircraft used Guadalcanal airfields to pound Japanese bases in the central Solomons and centering on Bougainville to soften them up for attack by powerful amphibious forces. These landings when they came were aimed at the reduction of Rabaul, the keystone to Japan's southwest Pacific defenses. Rabaul, located on the Gazelle Peninsula on the northeast coast of New Britain, and Truk in the Carolines, were strongholds and depots that supported Japanese jungle fighters determined to hold strategic positions seized in the first six months of 1942. They were spoken of in hushed and ominous tones by Allied servicemen. America's strategy for the Pacific offensives had its inception in Plan Orange. This pre-1941 joint Army-Navy plan to govern U.S. actions in event of war with Japan called for a westward advance across the Central Pacific and had its roots in strategic thinking that dated to the turn of the century. MacArthur's strategy was dictated by the first eight months of the Pacific War. It rested on the need to defend Australia and New Zealand and the sea routes from the United States to those countries and on MacArthur's desire to honor his pledge to return to the Philippines.

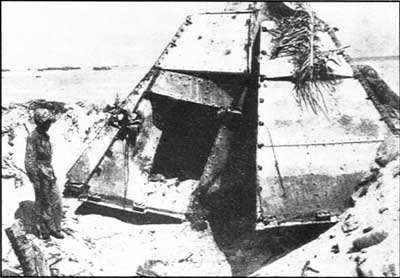

Operation Galvanic, directed against Tarawa and Makin islands in the Gilberts, taught costly lessons to Allied amphibious assault landings in their initial attacks on low lying coral-fringed atolls. Coordinated with a series of carrier air attacks on bases in the Marshalls, Carolines, and on Nauru, American forces belonging to Nimitz' Central Pacific command struck in late November. Marines of the 2nd Division landed on Betio in Tarawa Atoll. Soldiers of the 27th Division landed on Makin. It took four days to secure the islands from Japanese troops and elite members of the Special Naval Landing Forces, who fought to the death. Elsewhere, on the Asian continent, the "Forgotten War" was taking its toll in the China-Burma-India theater. An Allied military folk hero emerged from the Assan jungles to wreak havoc on Japanese jungle fighters 200 miles inside their lines. Thirty-nine-year-old Orde Charles Wingate, a Scot, led several thousand English, Gurkhas, Kachins, Shans, and Burmese across the Chindwin River into northern Burma. Known as Wingate's Chindits, named after the ferocious stone lions that guard Burmese temples, these largely forgotten forces destroyed bridges, tunnels, and railways, and delayed Japanese troop movements. The tide of war changed in favor of the Allies. The "battlewagon" U.S. Navy of 1941 had been replaced by faster, more heavily armed battleships and cruisers and Essex- and Independence-class aircraft carriers. American factories were producing the tools of war at far faster rates than the Japanese, and the Allies' superiority in firepower and numbers began to tell.

|