| The War in the Pacific |

|

|

PACIFIC ENCOUNTERS: RELIGION

Traditional Religion When faced with the incredible dangers and uncertainties posed by World War II, Pacific Islanders protected themselves with all the resources at their disposal. The traditional means involved calling upon powerful spirits for assistance, usually the spirits of deceased ancestors. Even areas where people drew upon Christian ritual and belief to survive the ordeal, traditional magic and sorcery were often employed to supplement the arsenal of spiritual defense. Magic and Sorcery Islanders in many areas used fight magic and hunting magic during dangerous situations. Many who were recruited into military units tell of relying upon magic to avoid detection and injury in battle. By chanting the proper words or employing the appropriate ingredients, one might disorient the enemy or cause his bullets to miss the mark. A Solomon Islander who helped evacuate a group of nuns by paddling them across the open sea says that they were saved by a traditional ("custom's") priest who uttered a spell to make them invisible to Japanese planes overhead. Many island cultures found new uses for finely honed sorcery practices designed to attack traditional enemies. Most Americans fighting in the Solomons were probably not aware that they had new allies on Ambrym in Vanuatu where sorcerers wanted to help their friends by directing spirit attacks against the Japanese. In parts of Papua New Guinea, people attributed Japanese successes over Australians to their use of magic and sorcery. Cults Momentous and mysterious events such as those of World War II were ultimately explained in religious terms, whether traditional or Christian. In some parts of Papua New Guinea, people who saw Japanese for the first time speculated that they might be the returned spirits of dead ancestors—they were obviously powerful enough to have forced a quick European evacuation. Attempts at explaining these bewildering events sometimes gave rise to cults aimed at attaining new forms of power and wealth unattainable in the old colonial world. In Belau, the Modekugei religion was developed by those Belauans who refused the Japanese head tax. It incorporated a number of anti-foreign features. When cult prophets in some areas overtly challenged Australian or Japanese authority they met with disastrous results. The Australians executed nine leaders of an anti-white cult near Vanatinai (Sudest) for their role in the murder of a district officer attempting to re-establish colonial control at the end of 1942. The Japanese beheaded three cult leaders in Buka, and killed hundreds of cultists in Irian Jaya.

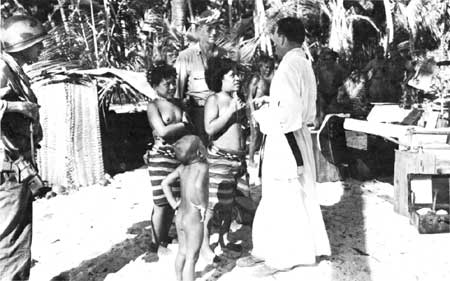

Christianity In the small islands and coastal regions where most of the war in the Pacific was fought, local residents had a long history of contact with outsiders. The hundreds of thousands of newcomers who came into the region for the first time during the war frequently expressed surprise at local people's sophistication with Western ways. Christianity, more than any other element of Western culture, symbolized Islanders' previous contact with the wider world. Shinto The Japanese in their 30 years in Micronesia appear not to have actively promoted Shinto religion as a replacement for either Christianity or traditional practices. They did, however, share a common concern with ancestors. On Belau, the approach of war brought the construction of an important Shinto shrine which, for the first time, was used by both Japanese and Belauans. This joint worship—praying for national victory in war—signified a new solidarity between Islander and outsider, just as church services did elsewhere in the Pacific. Co-worship For those Islanders who practiced it, Christianity was the single greatest symbol of their common bond with the Allies. Both Islanders and Allied soldiers possessed knowledge of Christian rituals such as praying, singing hymns, and attending church services and funerals. By jointly engaging in these activities, they demonstrated a degree of shared culture highly significant to both parties. Allied chaplains regularly conducted church services and administered communion to Islanders, whether in their villages or on military bases. For their part, island catechists and priests assisted in these services and, on some occasions, organized their own ceremonies. Resistance Just as Christianity provided an important bond with Allied troops, it was sometimes a barrier to acceptance of the Japanese. In some Christian strongholds, Japanese evoked strong resentment by mistreating missionaries and desecrating churches. On Guam, the Chamorro population saw their cathedral turned into a jail to confine captured Americans, and then an entertainment center where Islanders were called upon to perform traditional dances. By the end of the war about 200 foreign missionaries had died in Papua New Guinea. People who had evacuated their villages along the coast found themselves without either priest or church, and thus without the spiritual protection and strength they long sought through Christianity. A major part of "liberation" for many peoples in Japanese-occupied islands was the renewal of Christian ritual life. In Cape Gloucester, New Britain, two village catechists who had hidden the church goblets in the forest brought them out for their first church service in years after Allied troops retook the area. |