MENU

![]() NPS 1933-39

NPS 1933-39

|

Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s: Administrative History Chapter Six: The National Park Service, 1933-1939 |

|

C. Regionalization

None of the organizational changes made in response to the expansion of the park system in the 1930s would have greater long-term ramifications for administration of the Park Service than the establishment of regional offices in 1937. The creation of a new level of administration between the Washington office and the field was not, it must be made clear, a new idea. Park Service officials long had been concerned over the difficulty of effectively supervising and coordinating a widely-scattered system of parks and monuments from Washington, D.C. [41] During the 1920s the Service had established field offices in Yellowstone National Park, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Denver, Portland, and Berkeley. [42] These offices performed specific functions--landscape architecture, sanitation, engineering, and education (interpretation) for example--and did not exercise any general administrative or supervisory control over parks and monuments. A more immediate example of regionalization was the system developed to administer the Civilian Conservation Corps described on pages 77-96. In fact, because such a large number of NPS employees were involved directly in ECW, Director Cammerer stated in 1936 that the Service was already 70 percent regionalized. [43]

At a 1934 park superintendent's conference, held while preliminary discussions regarding regionalization were underway in the Washington office, it became clear that many people in the field as well as in the Washington office believed that the problem of communication was becoming critical as the Park System expanded. Reacting to a suggestion that the Park Service adopt a regional system roughly similar to that already employed by the Forest Service, Frank Pinkley, Superintendent of the Southwest Monuments, indicated that he had become increasingly concerned with the separation between the Washington office and the field, and that of "at least twenty different superintendents" with whom he had discussed the matter, all were of the same opinion. [44] Speaking for superintendents of the new historical areas, B. Floyd Flickinger of Colonial seconded Pinkley's observations, and indicated that he believed that the greater coordination that would come from regionalization was especially critical for the historical areas. [45] None of the superintendents spoke out against regionalization at the conference Yet, while those superintendents from cultural areas were enthusiastic over the possibility of regionalization of the Service, many of the superintendents from the natural areas were less so. While agreeing that "anyone in the field for years past must have realized we would have to come to some form of regionalization," John R. White of Sequoia National Park cautioned:

My observation of the Forest Service system would lead me to think it has been built up much too heavily. We should take precautions at the beginning not to build up the regional system and let it go too far, because some five or ten years from now when there is need for economy it may be taken from us. [46]

Actually, White continued, a more economical solution to the problem of communication than regionalization might be simply to have the superintendents travel to Washington more often. [47]

The plan advanced before the superintendents in 1934 would have established as many as five regions determined by classification of areas. Two regions would have incorporated cultural areas--one the Southwestern monuments, the other the military parks and monuments. [48] The scenic parks and monuments would have been divided among as many as three regions. [49]

The chief executive for each region would be responsible for overseeing that the policies and principles enunciated by the Washington office were implemented by field personnel. To facilitate communication between the Washington office and regions, one of the regional directors would be required to be in Washington at all times. [50]

Because of funding problems, it was believed that at least for the short run, the regional director would be a "qualified superintendent." Seemingly, the superintendent who served as regional director would not be relieved of his duties in the park.

Little was done, apparently, to follow up the discussions held in 1934. It was not until January 26, 1936, that Director Cammerer appointed a committee headed by Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson to study the question of regionalization and submit a plan. [51]

In mid-February, the committee forwarded to Cammerer a plan of "a simple organization that can be manned and administered from trained personnel and money now available." [52] The regional system proposed would, the committee said, bring the director and his assistants back into a more intimate touch with the field. It would allow greater supervision of the field, while preserving the autonomy and individuality of the parks. Administrative decisions could be made in the field rather than in Washington, and because the proposal would strengthen the influence of professional branches, those decisions would be based on the best technical advice. The system would, finally, provide greater channels of promotion from park to park, parks to region, and regions to Washington. Because promotion opportunities would occur in the various branches, an individual could advance within his profession, and not be necessarily diverted into administration [53].

The memorandum discussed above did not spell out the make-up of regions. That came several days later. The proposed system was based on a combination of unit classification and geography similar to that suggested to the superintendents in 1934. [54]

Region 1, with Chief Historian Verne E. Chatelain as the recommended regional director, would include all historical and military parks, monuments, battlefield sites, and miscellaneous memorials east of the Mississippi River. [55] Region 2, the second region established primarily on a classification of areas would have been headed by Frank Pinkley, Superintendent of the Southwestern monuments. Pinkley's region would have included the southwestern monuments as well as Mesa Verde and Carlsbad Cavern national parks, and Petrified Forest, Wheeler, and Great Sand Dunes national monuments.

The remaining three regions would have been headed by superintendents of large natural parks--C.G. Thompson of Yosemite (No. 3), Superintendent O.A. Tomlinson of Mount Rainier (No. 4), and Roger Toll of Yellowstone (No. 5). [56] The primary division was geographical and the regions would have included both natural and cultural areas:

No. 3

Areas: Yosemite, Sequoia, General Grant, Lassen Volcanic, and Hawaii National Parks, and Lava Beds, Muir Woods, Pinnacles, Devils Postpile, Death Valley, and Cabrillo National Monuments.

No. 4

Areas: Mount Rainier, Crater Lake, Glacier, and Mount McKinley National Parks, and Mount Olympus, Oregon Caves, Craters of the Moon, Glacier Bay, Katmai, Old Kasaan, and Sitka National Monuments.

No. 5

Areas: Yellowstone, Grant Teton, Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, Wind Cave, Bryce Canyon, and Zion National Parks, and Cedar Breaks, Big Hole Battlefield, Lewis and Clark Cavern, Verandrye, Devils Tower, Jewel Cave, Shoshone Cavern, Fossil Cycad, Scotts Bluff, Timpanogos Cave, Dinosaur, Lehman Caves, Grand Canyon, Holy Cross, Colorado, and Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monuments.

It was believed that eight existing and projected parks--Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, Platt, Hot Springs, Isle Royale (projected), Mammoth Cave (projected), and Everglades (projected) could function as they did for the present, although it was recommended that when Mammoth Cave and Everglades were established they would be coupled with Great Smoky Mountains, Platt, and Hot Springs into Region 6.

On March 14, Acting Director Arthur Demaray, forwarded a memorandum that described in detail the responsibilities of the proposed regional offices. Duties and responsibilities would certainly change over time, he said, but the following were representative of the work that it was proposed to transfer:

Field problems and investigations incident to new park and park extension projects.

This work is now handled by specially assigned superintendents or other field and Washington Office officials.

Direct Service activities as they relate to national and state park ECW and other emergency programs.

Cooperate with Federal, State, and civil agencies, legislators, etc., in connection with the furtherance of national park work and the emergency programs supervised by this Service.

They also would work with the State Planning Boards in connection with the formulation of harmonious improvement programs.

Handle National Park Service public contacts and publicity.

The publicity relating to the various parks and monuments in each region would be cleared through the Regional Office so that proper and adequate information could be given to the press. The special ECW public relations men, who have been appointed by the Secretary, would be retained.

Disseminate departmental and Service policies and regulations to the field areas within the regions and require compliance with such policies and regulations.

The Service field auditors would be attached to, and work out of, the Regional Offices. These auditors also would supervise the accounting work of the field units.

The survey of historic sites and buildings and the water resources survey, funds for which will be provided when the pending Interior Department Bill is enacted, would be conducted under the supervision of the Regional Officers.

Supervise the conducting of training classes for various types of field personnel, whenever practicable, with a view to increasing their knowledge of Service policies and standards and to develop those in the lower salary brackets for more responsible positions in the Service.

Coordinate the technical work of the Service to be carried on in the regions, through the engineering, landscape, forestry, historical, and other technical assistants of the Regional Officers. This will maintain and strengthen the influence of the professional, scientific, and technical agencies of the Service, and will facilitate closer inspection of all types of work carried on in the areas administered by the Service.

Approve standard plans of the Service to avoid the necessity of having to refer them to the Washington Office for approval.

Receive and answer routine communications from the field officials within the regions without referring same to the Washington Office. [58]

The Service would go slowly with regionalization, Demaray concluded, and would enlarge the authority of the regional directors only when such action was justified by experience. [59]

Secretary Ickes answered Cammerer's request on March 25. Reflecting his well-known antipathy for bureaucracies, Ickes wrote that he was reluctant to agree to the creation of offices outside Washington "because it would be only a question of time until a bureaucratic field force would become established to the detriment of the Washington office." While he recognized that Washington officials had to be "fully informed of administrative problems and actions," he did not believe that creation of regional offices would contribute to that end. [60] Rather, he believed that the appointment of district supervisors in the Washington office would be more effective, and instructed Cammerer to revise the proposal accordingly.

Ickes was not the only one to express reservations regarding regionalization. A flurry of letters to the secretary, which Cammerer believed was inspired by the National Parks Association, all indicated a concern that the grouping of historical and natural areas would be to the detriment of the latter. [61] Within the Service many "old-line superintendents object to the concept as an unwarranted intrusion on their ability to communicate directly with the Washington Office, and many rank and file personnel saw it as a barrier to career advancement." [62]

Director Cammerer believed that much of the opposition to regionalization from both groups would be dissipated by appointing "old-time" Park Service men to head the various regions. [63] While opposition to regionalization did not immediately disappear, Cammerer and his deputies were able to blunt the efforts of it, and convince Secretary Ickes.

On January 21, 1937, more than two years since regionalization was first discussed at the Annual Superintendent's Conference, Secretary Ickes initialed his approval of a regional system that would be implemented after the end of the fiscal year. [64]

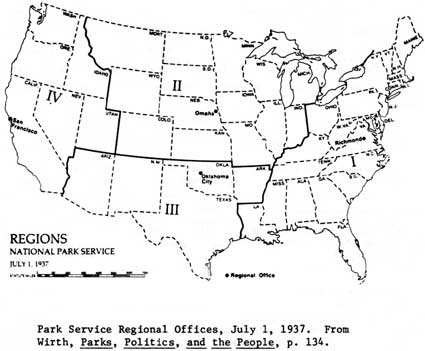

Accordingly, on August 7, 1937, Director Cammerer issued a memorandum that implemented regionalization of the National Park Service. The plan approved by Secretary Ickes established four geographic regions:

Region I

Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida.

Region II

Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Montana (except Glacier National Park), Wyoming, and Colorado (except Mesa Verde National Park and the Colorado, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Hovenweep, and Yucca House National Monuments in Colorado).

Region III

Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona (except the Boulder Dam Recreational Area), Mesa Verde National Park and the Colorado, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Hovenweep, and Yucca House National Monuments in Colorado; and Rainbow Bridge, Arches, and Natural Bridges National Monuments in Utah.

Region IV

Washington, Idaho, Oregon, California, Nevada, and Utah (except Rainbow Bridge, Arches, and Natural Bridges National Monuments); the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii; Glacier National Park in Montana; and Boulder Dam Recreational Area in Arizona and Nevada. [65]

Interestingly, of the first four regional directors only one, Thomas Allen, Jr. (Region II), had been a superintendent of a natural park, although Carl P. Russell (Region I) and Frank Kitteridge (Region IV) had considerable National Park Service experience. [66] Herbert Maier, who was named acting director of Region III, had been in charge of the Service's CCC and emergency activities of Region III (CCC). In addition, the associate regional director would be the current CCC regional officer. [67]

The implementing memorandum made it clear that the Washington office intended to proceed cautiously with regionalization, and subsequent memorandums issued throughout the rest of the decade amplified, refined, or in some cases altered functions of the regional offices. [68] Nevertheless, the outlines of the organization that would administer the National Park Service in the future were drawn, and it reflected Secretary Ickes concern that the field offices not rival the Washington office:

Duties and Responsibilities:

The headquarters of the Regional Directors are located at Washington, D.C., and at their respective field offices. One of the Regional Directors will be on duty in the Washington Office at all times. Contacts between the Washington Office Branches and the Regional Offices will be handled through the Regional Director on duty in the Washington Office. Correspondence between the Washington Office and the Regional Directors shall be routed through the Regional Director on duty in the Washington Office.

The Regional Directors are the Director's administrative representatives for the field and are generally responsible for the furtherance of the Service's regular and emergency programs in the regions. They will be in general charge of public contact work in accordance with approved plans and policies, and of the development of cooperation with Federal, State, and local agencies, legislators, State planning boards, etc. They will have supervision over, and be responsible for, the coordination of the water rights and historic sites and buildings surveys, and of the park, parkway, and recreational area study. They will exercise administrative control over the technical forces in their respective regions.

The relationship between the Regional Director and the regional technicians shall correspond to that existing in the Washington Office between the Director and the heads of the Washington Office Branches.

The accepted policy that the Superintendents and Custodians are responsible for all activities in the parks and monuments will obtain. The Regional Directors shall study the problems in the national park and monument areas in collaboration with the Superintendents and Custodians so that the policies and practices of the Service will be handled uniformly, and so that there will be continuity of policy, regardless of individual interpretations and changes in personnel.

The National Capital Parks, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Project and similar memorial projects, and the Blue Ridge and Natchez Trace Parkways and similar parkway projects during the planning and construction stages shall be handled independently of the Service regions, except where experience dictates that cooperation between the Regional Director and the official or officials in charge of the activities mentioned, is advantageous to the Service.

Special duties and responsibilities may be assigned by the Director to the Regional Directors for handling outside of their regions.

Regional Personnel in Service Areas:

The Regional Directors shall coordinate the travel of the technicians in their respective regions. They shall advise the superintendent or custodian as far in advance as possible regarding a contemplated visit of Regional personnel to his park or monument.

The personnel of the Regional Office assigned to a particular national park or monument area shall work under the administrative direction of the superintendent or coordinating superintendent, if one has been designated, of that park or monument. This procedure shall also apply to all areas which have been placed under the administrative supervision of a superintendent. In all other areas administered by the Service, assigned Regional Office personnel shall continue to be under the administrative direction of the proper Regional Director.

Program Approvals:

Development, protection, and interpretation programs are to be approved by the Director prior to the preparation of any plans for projects thereunder.

Plan Approvals:

Regional Directors shall approve plans covering projects in national park and monument areas, regardless of the source of funds, except those covering road projects, new trail projects, major structures, major buildings, and operator's plans, as such plans must continue to be approved by the Director; however, they shall continue to be routed through the Regional Office.

Reports:

Copies of all regular and special reports and of the annual and emergency estimates and programs submitted by those in charge of the National Park Service areas in each region shall be sent to the Regional Director thereof.

New Areas:

The initiation of any investigation of a proposed new park or monument area must emanate from the Director, who will instruct either the Regional Director or designate some other especially qualified official to handle such investigation. He will advise the Regional Director of the contemplated investigation and, if considered advisable, will request the Regional Director, or a representative of his Office, to accompany the investigating party. Copies of all communications regarding a proposed new area shall be sent to the proper Regional Director. [69]

Establishment of regional administrative units was an experiment. Within a short time it proved its effectiveness to both Washington officials and field personnel. In his annual report of 1938, Director Cammerer wrote:

Establishment of closer relationships with executives charged with various administrative units of the Federal park system and acceptance of a greater degree of responsibility for regular and emergency programs in those areas were the most marked results of the transition from the previously existing emergency regionalization to the present national park regional organization. [70]

The following year, while calling for establishment of one additional region, the park superintendents resolved:

As a means of establishing closer relationship with the various administrative units of the National Park Service and providing better coordination of field and Washington Office activities, it is agreed that the general principle and practice of regionalization effected by the Director's memorandum of August 6, 1937, and amendments have already proven their worth and are heartily endorsed. [71]

Chapter Six continues with...

Retrospect

Top

Last Modified: Tues, Mar 14 2000 07:08:48 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/unrau-williss/adhi6c.htm

![]()