|

Stories in Stone

|

|

CHAPTER II

THE IDEAL AND THE PRACTICAL

ONE of the objects of this book is to put on record some of the tales that seem worth perpetuating, and certain incidents that seem worthy of serious consideration. This chapter does not exhaust the stock. It merely suggests lines of thought that have interested me and that I hope may interest you.

It has been said that scientific men have a message for the world but do not know how to tell it. In a measure this may be true, for the study of natural science is relatively new and its followers have been so intent on discovering its fascinating mysteries that they have paid little attention to the manner of describing them. However, the mode of expression is of secondary importance. The facts count for more than the language, just as a painting is more important than the frame in which it is exhibited.

A Message

The message which I am trying to present seems to be so interesting that the manner of presentation should matter little. The rhetorician who is looking for literary perfection may look elsewhere. I am concerned chiefly in presenting to those who are eager to know of them the things which fascinate me. For this reason I am writing chiefly for the young men and the young women who read as they run, and for the boys and girls of today who are to be the seers of tomorrow, and for the lovers of God's great outdoors who want fact rather than fiction. I am writing for those people who are young in heart although their hair may be as white as mine, and for those who, like myself, find facts stranger than fiction and more exciting than the machinations of fancy.

I am trying to do for some one else what a good friend did for me years ago—a friend whose hair is now a crown of glory on his kindly brow. Let me digress a moment.

Inspiration

Years ago in the little Pennsylvania town where the first years of my life were spent, entertainments were rare, movies had not been invented, and good stereopticon pictures were unknown to me. But one boy from that town had chosen to be a teacher of geology. He had obtained what we then called a magic lantern, a crude apparatus for projecting pictures onto a screen by means of light from a kerosene lamp. The lantern would be laughed at today, and the slides—what crudities they were! But to me they were wonderful!

Each vacation when the geologist came home the magic lantern came with him and the pictures were exhibited. I counted the months, the weeks, and the days from vacation to vacation, and the hours of the day until finally I sat in open eyed wonder gazing at those imperfect representations of extinct animals and ancient landscapes. My imagination was stirred profoundly and there settled upon me, never to depart, a determination to know something of the wonders of this old earth of ours.

If through the imperfections of this book, which may be as obvious to some readers as those of the magic lantern pictures are to me now, I can pass this enthusiastic determination on to some one else, I shall not have written in vain.

There are two general classes of readers that I hope to reach: those who would turn a knowledge of geology to practical uses, such as the teacher and the mining engineer, and those who, though busy most of the time with other things, turn to the mountains and the canyons for their recreation. It is of these travelers that I am now thinking chiefly, for in this commercial age there is need for idealism. All work and no play sends men to the madhouse.

Idealism and Commercialism

The idealists are numerous—those who would like to know the secrets of nature but who have been denied the opportunity of learning them. The intense interest in natural scenery is eloquently revealed by the crowds that flock to the national and municipal parks. Many of the public playgrounds are not yet equipped for entertaining guests or even for recording the number of visitors; yet the available records show that in the year 1925 between two and three million people took enough interest in the natural features preserved in the parks to spend much time and money to see them.

But while idealism should be fostered, commercialism should not be discouraged. Both are necessary, for both body and mind must be fed. Long ago it was said of certain things which some thought were more important than other things, "things ye ought to have done and not to have left the other undone." There are many practical reasons why the laws of nature should be understood. Let me illustrate.

The Man Who Knows

A few years ago a man who had worked hard and long to keep his family comfortable in a modest home tried to dissuade his son from "wasting time and money" going to college. He objected especially to the study of what he termed "useless things," such as geology. But the young man was not dissuaded. He had observed that boys who know find better opportunities than those who do not know. He liked college and he liked the study of geology. He continued to follow his own judgment in the face of parental opposition.

A few years later this boy was placed in charge of one of the field parties of the United States Geological Survey and sent out to gather information on the natural resources of the country. A part of his duty was to employ other men and to direct their activities. Among those employed by him was his father, who was given a position as teamster. The older man knew no geology, but he could take care of horses and could make himself generally useful about camp. If he remembered his former opposition to his son's ambition he said nothing of it. The son remembered—but he also said nothing. A few years later the young man was put in charge of the field operations of a large oil company, and in due time he developed a business of his own.

The older man was like many others who are too short-sighted to see the great opportunities open to those who are prepared. But fortunately there are many who, like this younger man, are far-sighted enough to see that there are possibilities in the future and to prepare for them.

Why Worry?

The question is heard on every hand, "What's the use of learning things that will never be needed?" What boy has not been scolded for dreaming when he should have been at work? What girl, for building air castles and missing her lesson? There is no help for it. The scolding must be endured. The parent has forgotten his daydreams, and the teachers air castles have fallen. But who shall say what has been the life long influence of some childish vision?

Demand for Geologists

Never in the history of the world has there been greater demand than now for men in the natural sciences. This is true particularly in geology. Never before has there been so insistent a demand for the products of the earth—products that are being used in immense quantities. More coal is needed; it is difficult to get enough iron to supply the demand; there is always a ready market for gold and silver; and the cry for gasoline and other products of petroleum is becoming more and more feverishly insistent. Hundreds of other products of the rocks find ready market. There is a constant demand for the services of those who know where to find the minerals and how to extract them from the rocks. There is unending search for potash and there is fear that the supply of platinum will fail. Nitrates are so scarce and so much in demand that efforts are being made to supply them by artificial means.

The call for increased production of food is world-wide. Food is the product of the soil, and soil is produced from the rocks. In a very real sense the production of food is a geologic problem. The character of the soil varies with the kind of rock from which it is produced. The soil of a limestone region is quite different from that of a sandstone region. Each is adapted to certain kinds of crops and not to others.

|

|

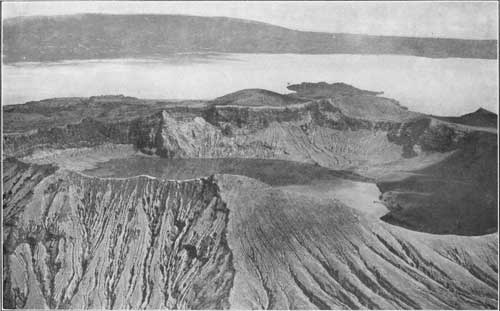

PLATE III. CRATER OF

TAAL VOLCANO, PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, AS SEEN FROM AN AIRPLANE.

Official photograph U.S. Army Air Service. |

|

|

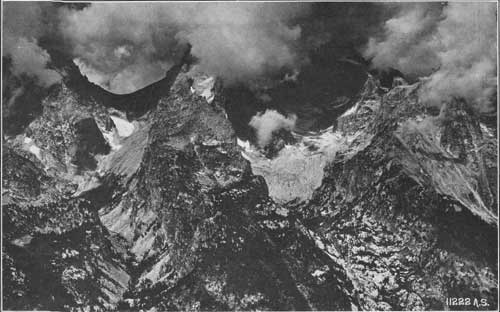

PLATE IV. EASTERN

FACE OF THE GRAND TETON, IN WESTERN WYOMING, AS SEEN FROM AN

AIRPLANE.

The lower slopes are covered sparsely with tall pine trees. The middle slopes are dotted with ice fields and with talus slopes that mark great accumulations of slide rock. The high peaks rise steeply into the clouds. Official photograph U.S. Army Air Service. |

Practical Applications

Recently an important viaduct was planned to carry a railroad across a valley. The plans called for a pier near the center of the valley. The nature of its foundation was not properly determined until work on other parts of the viaduct was far advanced. Apparently the engineers in charge did not realize—perhaps did not know—that this valley lies in a region where the glaciers of the Great Ice Age had filled preexisting valleys with sand, clay, and boulders.

As the work of construction progressed it became evident that the center pier had been located in the course of an old channel that had been filled with clay and quicksand. For a time it seemed doubtful whether a good base could be found for the central pier, and other parts of the viaduct were finished long before an adequate foundation for the central pier was reached. A little geologic knowledge and enough forethought to determine the underground conditions before plans were finished might have saved much trouble and prevented much waste of time and money.

Several years ago a dam was built across the Pecos River, in New Mexico, to store water for irrigation. The bed of the reservoir consisted in part of gypsum. A slight knowledge of geology should have warned the promoters that a reservoir on beds of gypsum was about as suitable for storing water as a cup made of sugar would be for serving tea. The water soon found underground passages, which were rapidly enlarged, for the water took into solution the gypsum through which it flowed. At the time of my visit these underground passages were carrying the entire flow of the river and the reservoir was empty.

Some attributed the failure of this reservoir to the inexperience of those who had charge of it and argued that it might have been saved by skilled engineers. Settlers were depending on the reservoir for the irrigation of their crops. The United States Reclamation Service tried to save the community from ruin and set for its experienced engineers the herculean task of outwitting nature.

Hercules had succeeded in deflecting a river from its natural course; so also did the engineers. But although a new reservoir site was chosen and a dam built to control the water of the river, the water refused to be held in control. Hercules himself would not have been able to hold water in a gypsum basin. After years of fruitless effort no way has been found to stop all the leaks, and the large storage reservoirs here are rated as failures.

One more example may be cited to illustrate the need of understanding the nature of the rocks where dams are to be constructed.

The Zuni Indians needed a storage reservoir for irrigation, and a site was selected on the Zuni River in western New Mexico, where lava from a volcano, now extinct, had flowed across the old valley. After this lava had cooled and hardened the river had cut a narrow channel through it. Here the engineers constructed a dam, but before the reservoir was filled the water found a way of escape through the rocks at one side of the dam.

When the molten lava had spread over the country in past ages it had buried the soil and loose sand of the old surface in the bottom of the valley. As the water rose behind the dam the pressure finally became great enough to force water through the unconsolidated material under the lava, and much of the fine material was washed out, allowing the undermined lava to break and settle in a fractured mass, through which the water easily made its way.

Theory and Practice

The benefits of a knowledge of geology in mining are so obvious that they should require no discussion; and yet invidious distinctions are frequently made between "practical knowledge" and "theoretical guesses," or, as some express it, "theoretical nonsense." Theory and practice are equally useful and are dependent on each other. Practical results frequently follow the application of theories of some one who has thought out possibilities.

Prophetic Geology

The science of geology attains one of its highest objectives when it presents a deduction that points the way to obtain practical results. An illustration of such a deduction was given in connection with the proposed disposal of chemical waste from one of the Government plants started at Sheffield, Ala., for the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen. This plant is so situated that surface drainage from it would be difficult and expensive, and, furthermore, there seemed to be danger that the discharge of chemical waste into the neighboring streams would produce bad results. The problem was incidentally submitted to a geologist, who ascertained that the plant rests on limestone, a kind of rock that is likely to be honeycombed by caves. He advised trying underground drainage by means of drill holes. The plan proposed met with the usual opposition from so-called "practical men," who made the customary disparaging remarks about "scientific theories," but a trial hole was started close to a small lake near the plant, and when the drill reached a depth of 175 feet and a trench had been dug from the lake to the hole the lake water quickly disappeared through some subterranean passage.

Science and Utility

An example of the commercial application of a theory came to light some years ago. A coal mine in New Mexico was abandoned when the coal bed seemed to have been lost through faulting. The rocks had been disturbed by some earth movement, and it was supposed that where the coal disappeared the bed had been faulted out of place and eroded away. On this supposition the mine was abandoned, the camp was deserted, and the railroad connections were removed.

A geologist visited the deserted mine and found in the rocks the fossil tooth of an extinct mammal. By means of this tooth the geologic age of the rocks was determined. The geologist was then able to assure the officials of the coal company that their coal bed had not been eroded away. On this assurance a drill was put in operation, the lost bed was located, and the railroad was rebuilt. A new mine was opened and has been in operation ever since.

Nevertheless memory is short and men here, as in many other regions, with supercilious smile ask the geologist "What's the use of wasting time looking for curious rocks; what good are they; can't you find something useful to do?"

If we think for a moment of the quantities of mineral matter used we will not wonder at the increasing demand for men who understand geology. Nearly a billion and a half tons of coal were mined in 1925. Men are wanted who understand coal.

Half a century ago petroleum occupied so humble a place in the industrial world that it attracted little attention. At present the world is using oil at the rate of more than a billion barrels a year; and we take pride in the fact that two thirds of this amount is produced in the United States. The rapid expansion of the oil industry and the ever-increasing use of petroleum has created a demand for geologists who are able to see in the rocks the signs that point to oil. In petroleum regions the geologist is king. No one there asks, "What's the use?"

|

|

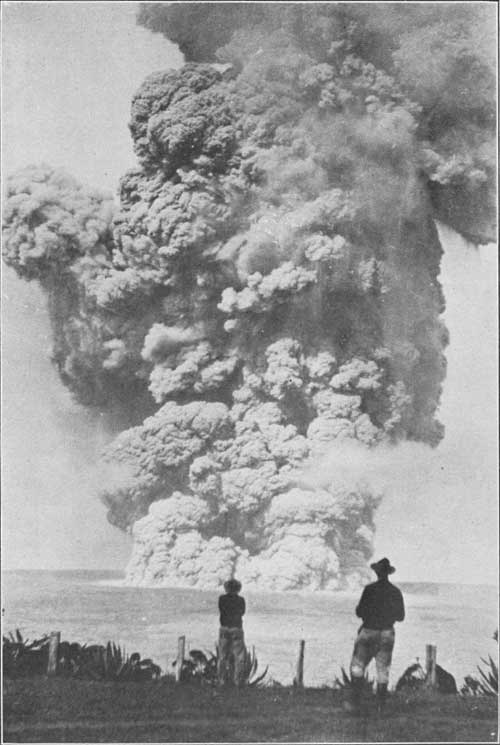

PLATE V. THE GREAT

FIRE PIT OF KILAUEA SEEN FROM AN AIRPLANE AT A HEIGHT OF 4,000 FEET,

NOVEMBER 9, 1923.

This opening, about 3,500 feet across, is the vent of chimney of the volcanic furnace under the mountain. It may be considered the safety valve through which escape the gases that, if confined too long, might blow off the top of the mountain. Such an explosion did occur May 22, 1924, during which the pit was greatly enlarged. (See Pl. VI.) Official photograph U.S. Army Air Service. |

|

|

PLATE VI. A VOLCANIC

ERUPTION OF THE EXPLOSIVE TYPE.

The dust cloud of Kilauea, 11,500 feet high, shot out of the fire pit (see P1. V) May 22, 1924, at a velocity of 780 feet a minute. The photograph was taken from the observatory, 2.1 miles from the fire pit. The indistinct parts denote clouds beginning to form as the hot vapor condenses. This explosion was a great surprise to those who were accustomed to regard Kilauea as a quiet and well-behaved volcano. Photograph by H. T. Stearns. |

Fossils and Oil

A few years ago a geologist busied himself in California collecting fossil shells, studying them, and giving them long names which no one else seemed to be interested in. Some inquired what could be more useless from a practical point of view than studying the remains of animals that had perished long ages ago? What possible interest could the business world, which paid the bills, have in these remains of extinct animals? What difference did it make whether the geologist gave a shell some unpronounceable name or tossed it aside as a useless curiosity? So argued those who did not know.

The geologist discovered in the course of his study that certain kinds of shells are found in rocks that contain petroleum. By close observation of the fossils he was able to determine where oil was most likely to be found, and by a knowledge of the structure of the rocks he was able to tell the drillers how deep they must go in order to penetrate the oil-bearing stratum.

Since that time this geologist has been connected with the production of oil, and by means of his knowledge of fossil shells he has been able to add more value in dollars and cents to the wealth of the country than the study of fossils has cost since the science of paleontology began.

Franklin's Reply

The question asked so often, "What's the use" of this or that investigation, was properly answered by Benjamin Franklin, who replied to a similar question, "What's the use of a newborn babe?"

It is often as difficult to explain the use of certain work as it is to foretell what a child may accomplish in life. The geologist has special difficulty in certain parts of the country in meeting insistent demands to know just why opportunity should be given for an examination of private property and why he should receive certain information that seems not to concern him. Inability to explain why an item of information may be useful is no proof that it is useless.

Many a man now recognized as a benefactor of his race was once regarded as an impracticable dreamer.

Illustrations

The story goes that a few years ago Professor Langley, then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, was trying to persuade Congress to appropriate money for experiments on flying-machines. "Useless waste of money" many said. "Crazy mortal!" said others. "A loon isn't to be compared with a man who thinks he can fly like a bird!" But one man wiser than the others said, "Let him alone. Some day he may stumble upon something worth while." Unfortunately the sensitive heart of the great scientist broke under the derisive laughter of the nearsighted public, but the man who tried to help him lives to watch exploits of air men such as were never dreamed of in Langley's day. He lives to see the world stand in awe before the accomplishments of aeronautics and to see men excel Columbus in daring flight around the world.

Let the dreamer alone! Some kinds of dreams come true.

Many stories are told of trivial circumstances that have led to important results. Everyone is familiar with the statement that the cackling of geese saved Rome. Many a great discovery has been made because of some little circumstance that hundreds have passed without notice.

From a tale familiar to mining men we learn that in 1902 Ben Paddock, riding over a rocky trail in western Arizona, noticed some gleaming particles in one of the rocks. Others had traveled the same way but had not seen the particles. They interested Ben, although he did not know what they were. He gathered as much of the rock as his horse could carry and took it to Camp Mohave, where he sold it for $500.00. Later the Vivian gold mine was opened where this ore was found.

Many a man walked over the placer grounds of California before their value became known. The gold-bearing rocks of Cripple Creek in Colorado were prospected for years before some one of keen observation found the ore.

Untold generations of ignorant savages roamed over the diamond fields of South Africa without knowing the value of the treasure beneath their feet. Many a white child played with the pretty pebbles before anyone knew what they were, until Doctor Atherstone recognized then as diamonds.

Some years ago a road was built through the Phoenix Mountains in Arizona. Many a traveler passed over the road, perhaps dozing across the weary miles or regretting the opportunities he had missed, so blinded with self-pity that he could not see opportunities at his feet. But one man of sharp eyesight and keen insight noticed some red substance in one of the rocks at the side of the road. He wondered what it was. Probably others had wondered. But here is the difference: this man took a piece of the rock and had it examined. The red material proved to be cinnabar, the mineral from which mercury or quicksilver is obtained. A mercury mine was opened where he found the ore.

It pays to be wide awake even in the dreamy desert.

Sometimes the element of chance interferes with our plans. Some curse their luck and others turn the chance to advantage. We are all familiar with the statement that had not Bunyan been imprisoned he would never have written Pilgrim's Progress. It is not pleasant to be imprisoned. But if we are, we may still continue to make progress in one way or another.

Misfortune led to the discovery of gold at Gold Road, in Arizona, in 1902. The story runs that Joe Jeneres, a Mexican prospector, had the misfortune to lose his burros. Forage was scarce and the animals strayed into the hills in search of food. In the desert the loss of animals is serious. Joe went in search of them. He found not only the burros but also the gold ore he was looking for. Soon thereafter the Gold Road mine was opened where the animals had strayed.

But while we are considering the geological application of the principle that "Great oaks from little acorns grow" we may do well to consider also that some little things start great growths of foolishness.

In a prospective oil field that I once examined, some one had found a number of small rock concretions commonly known as ironstones. They had nothing to do with oil. But some wag had solemnly informed the finder that they were oil beans. Thereafter the supposed oil beans were collected in great number as proof that oil was present over a wide area. No oil has yet been found there.

|

|

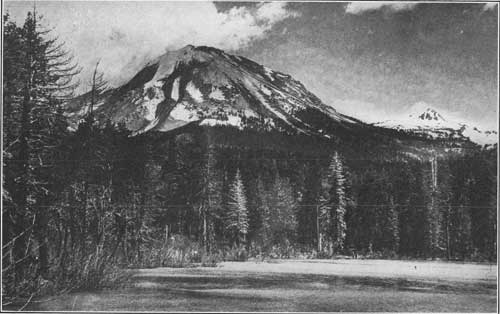

PLATE VII. LASSEN

PEAK, IN LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA, THE ONLY ACTIVE

VOLCANO IN THE UNITED STATES PROPER.

It is 10,465 feet high and was built up by lava extruded during a long series of eruptions. It stands in a region characterized by volcanic vents, hot springs, mud geysers, and other features resulting from igneous activity. |

|

|

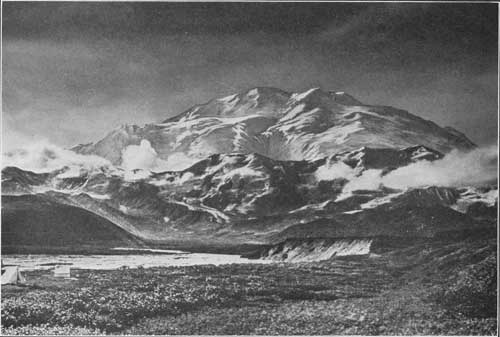

PLATE VIII. MOUNT

McKINLEY, THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN AMERICA (ALTITUDE 20,300 FEET), AS

SEEN FROM THE NORTHWEST AT A DISTANCE OF 15 MILES.

Photograph by A. H. Brooks. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

stories_in_stone/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 31-Dec-2009