|

Stories in Stone

|

|

CHAPTER I

WHAT'S THE USE?

An Invitation

WOULD you like to know something of the earth on which we live and how it is made to yield us the means of life and happiness? And would it interest you to recall some of the curious concepts that have centered around the origin of the earth?

Would you like to know the Grand Canyon, or is it enough just to read about it? (Plate I) Are you satisfied to be introduced to Niagara Falls (Plate II), or would you like to be intimate with this world-famous cataract and feel its great pulsing life? Is it enough to be gently sprayed from a safe distance by a geyser or do you wish to descend in comprehensive imagination into the seething caldrons beneath the surface and know the forces that produce an Old Faithful? Are you satisfied to know in some vague, indefinite way that there is a volcanic mountain known as Vesuvius and that a pit of boiling lava exists at Kilauea, or do you long to know really what causes a volcanic eruption such as that which formed the crater of Taal? (Plate III)

If these things interest you, perhaps you will browse with me through the quaint volumes cited in the closing chapters of this book and scan some of those early conceptions which contained the germs of truth from which have sprung many of the beliefs of the present day.

The development of belief concerning the origin and general history of the earth is as interesting to some as the physical processes of the earth are to others. Perhaps some will join with me in an intense interest in the development of the science of the earth and follow the growth of knowledge from a time when "the earth was without form and void" in the minds of men, through the long periods of intellectual gloom when only an occasional flash of light penetrated the murky atmosphere of superstition and ignorance, to the present time, when facts are being placed in orderly arrangement and when natural law is finding its proper recognition.

Standards of Value

Let us consider first some of the tangible things that are near at hand and that affect the course of our life day by day, then some of those intangible things that are less obvious but no less real. These things cannot be sharply separated any more than work and play can be sharply separated in real life. Both are necessary.

There is an ideal standard by which values may be judged, as well as a practical standard. A thing may be useful for increasing our material comfort, or it may be employed for broadening human knowledge and for touching the finer emotions. The science of geology stands the test of judgment by both standards. The mind as well as the body must be fed. The coal mine furnishes the means of bodily comfort; the oil field, the means of travel; and natural scenery, an important means of enjoyment.

The ability to interpret natural scenery properly depends on a knowledge of the forces which produced it. We may admire the beauty of a landscape or marvel at its grandeur, but we must know how it was formed before we can appreciate its full significance. A great canyon appears wonderful as we gaze into its depths; but it appears far more wonderful when we know how it came into being. A volcanic explosion like that of Katmai seems astounding. But astonishment does not satisfy the inquiring mind. To fathom such mysteries, men are willing to spend time and treasure and even to risk life.

From the earth we draw those material things which are necessary for life and happiness. The science of the earth is fundamental, for it treats of those things. This science guides us in the search for mineral wealth and aids us in understanding the forces which produced this wealth. A study of geologic processes leads to an understanding of the laws which contribute to our daily happiness, for these processes have been in operation from the beginning, shaping the earth into a pleasant place for human habitation. Thus practical considerations are not far separated from the theoretical. Applied geology and pure geology join hands.

Discoveries and Applications

It is quite impossible to foresee what applications may be made of a new discovery or how an understanding of a natural law may be applied. In the early stages of civilization discoveries were accidental. Primitive man probably learned by accident how to use a rude flint implement, and the Stone Age followed. Later, men discovered in some way that bronze tools were better than flint. The use of iron and copper and aluminum followed, and we are now learning to use materials that still seem somewhat mysterious, such as helium and tungsten and radium.

But learning new things is a slow process. The struggle out of the slough of ignorance is difficult and discouraging. The school of "hard knocks" has more graduates than any other.

Many have tried short cuts. Some there are who still believe it is possible to find the treasures of earth through the guidance of dreams and of charms. And many have faith in appliances which pass under the general name of "doodlebugs."

Principles and "Doodlebugs"

The hope of progress lies in understanding, and an ever increasing number of young people are going out to face Nature equipped with a knowledge of Nature's laws. In geology, as in every other field of activity, knowledge is power. It was a geologist who developed the fundamental principle that oil is found chiefly in anticlines and domes. The recognition of this principle has helped to increase the production of petroleum from a few barrels a day seventy years ago to nearly 3,000,000 barrels a day at the present time.

But a trained mind is necessary for taking advantage of even well established laws. The element of chance sometimes enters to confound the wise. The trained man assures us that the "water witch" cannot "smell" water any farther than can the man without a forked stick. Yet water is found in many a well that has been located by someone who used a hazel twig. The fact that underground water is present almost everywhere and that it would have been found with the same amount of effort in almost any other place does not seem particularly impressive compared with the fact that water was found where the hazel twig pointed.

Many oil wells and many bodies of ore have been located by the use of "doodlebugs." Most such wells are dry and most of the ore bodies located in this way are worthless, but occasionally a strike is made and is referred to as proof that the method is correct. The numberless failures are forgotten.

Some years ago a prospector in the Rocky Mountains learned that rich ore is to be expected where two veins cross. In his search for wealth he found a place where a tree had fallen across the prostrate trunk of another tree. He remembered that something "crossed" denotes rich ore but he had forgotten what it was that should be crossed. He dug his prospecting shaft where the tree trunks crossed and found ore. It so happened that a shaft anywhere near this point would have entered the body of ore which he found. But it was quite useless to tell him this. He had proved to his own satisfaction that something crossed denotes rich ore.

Pure Science Better than Pure Nonsense

Examples of this misapplication of correct principles might be multiplied indefinitely, but they serve no more useful purpose than to give warnings of what not to do. Much more useful are examples of a correct principle followed to a useful conclusion.

Underlying the art of geology is the so-called pure science, from which spring all the rules and guiding principles for practical geologic work, and many a line of research pursued in the cause of science with little thought of practical application has yielded information of great material benefit. Witness a certain study in glacial geology:—

Dr. W. C. Alden, of the United States Geological Survey, worked for years mapping with painstaking accuracy numerous glacial deposits and studying the behavior of the sheet of ice which overwhelmed Wisconsin in the Great Ice Age.

"Such a study is all very well for those who are interested in the story of the earth. But what's the use? It has no practical application." So argued the uninitiated.

When the study of the glacial deposits was undertaken, the present great network of automobile roads had scarcely been started. But soon after Doctor Alden's report was published engineers in Wisconsin needed gravel for building roads. The glacial gravels were found to be suitable, and Doctor Alden's map proved to be a valuable guide in finding them.

Considered only as a means of finding road metal this map is said to have been worth many times the entire cost of Doctor Alden's investigation.

Pure geology may be fitly applied to the interpretation of natural scenery, for the surface of the earth—the landscapes and the natural features that excite our wonder and delight—are all the results of geologic processes.

Geology and Scenery

Some of the choicest bits of natural scenery in the world are found in the wonderlands of America. Many of the best of these natural wonders have been reserved for the enjoyment of the public in national parks and national monuments, where they may remain forever unchanged in the form that Nature gave them. Each park contains a notable example of some special type of scenery. In Kilauea (Pls. V and VI) we may see the results of an active volcano; in Lassen Volcanic Park (P1. VII) we may see a mountain that was built up by volcanic eruption; in Yellowstone Park we may examine the results of dying volcanic activity; in Zion Canyon we may see a most remarkable example of a stream-cut gorge; and in the Grand Canyon we may behold the most sublime chasm in the world.

The national parks and monuments and many other tracts of land that might appropriately be reserved as parks are full of attractive scenes that are worthy of close study. Each park illustrates a special type of landscape, and each possesses scientific as well as scenic interest. These parks contain many of the natural wonders of the world.

Before much of the earth's surface was known to cultured people there were seven wonders of the world; now there are "seventy times seven."

I Want to Know!

But to the intelligent mind it is not enough that wonders are made visible. Such a mind is always reaching out after causes. "How did it happen?" is often the first question asked. "I want to know" is an exclamation so familiar that its real significance may be lost.

Probably no sentence in any language is more familiar than that accounting for the origin of the universe: "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth." After the exclamations of wonder commonly heard as a party of sightseers approaches a great cliff or enters a deep canyon, the first question usually is,—what made it?

Some may care little for the processes by which results are obtained. They are content to contemplate the finished product. But the genuinely appreciative observer is not satisfied with visible objects alone. With mental insight he goes back of the object to its primary cause. Back of a painting an artist sees the years of training that made the painter.

Few of us are content merely to see a cathedral. While we are enjoying its beauty we wish to know its origin and its history. We seek to know how and when the architect worked his dreams into stone.

Ruins—especially prehistoric ruins—become more interesting as the cloudy mystery of the past clears away. By whom were they made? What is their story?

In like manner the architecture of nature is fascinating in proportion to the measure of appreciative understanding with which it is viewed. To him who knows geology the earth is not a mass of dead rock; it is a living, pulsing body, ever changing by movements so deliberate and majestic that only by mental insight can we behold them. To him who knows, the mountain is not a forbidding pile of rocks; it is the visible embodiment of a fascinating story in the life of the earth. To him who has mental vision, the canyon is not a finished creation existent from the beginning; it represents only one stage in the process by which highlands are gradually torn down and swept into the sea: its story is still being told.

To understand and appreciate the natural scenery of the wonderlands of western America we must know at least the elements of geology, just as we must know conditions and methods of mineral deposition in order to prospect intelligently for the deposits of ore.

To this end, it seems appropriate to call attention, as is done in the closing chapters of this book, to some of the conspicuous incidents in the development of belief concerning the nature of the earth and to apply the ideas thus developed to the interpretation of scenery. I hasten, however, to assure you now that I have no intention of going exhaustively into the tiresome details of a dead past. Rather would I merely glance over its cloudy vistas and as quickly as possible note a few of the most conspicuous milestones in the course of events by which we have arrived at the present understanding of the earth and of the natural processes which brought it into being and adorned it with noble mountains, gorgeously colored canyons, and broad, verdure-covered plains.

|

|

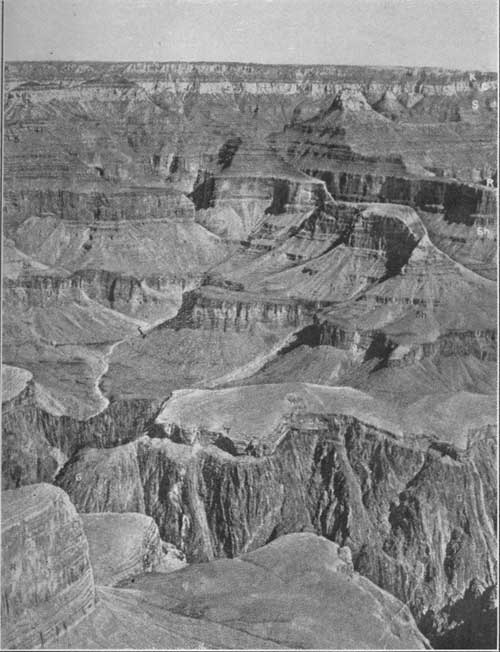

PLATE I. NORTH SIDE

OF GRAND CANYON AS SEEN FROM GRAND CANYON STATION.

G, Granite and gneiss; U, Sandstone, red shale and limestone (Unkar); T, Sandstone (Tonto) forming the bench called the Tonto Platform; Sh, Shale of Tonto group, lying directly on quartzite of Unkar; R, Limestone (Redwall); S, Red sandstone and shale (Supai); C, Gray sandstone (Coconino); K, Limestone (Kaibab). The Redwall butte in the center is Cheops Pyramid; beyond are Buddha and Manu temples. Background is Kaibab Plateau. |

|

|

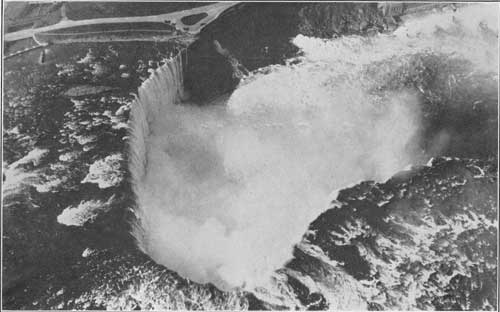

PLATE II. NIAGARA

FALLS AS SEEN FROM AN AIRPLANE, LOOKING NORTHEASTWARD

(DOWNSTREAM).

The rough surface at the bottom of the photograph represents the rapids above the V of the Horseshoe Falls. In the upper right hand corner is the power plant. Official photograph U.S. Army Air Service. |

Aids to Understanding

And so, renewing the invitation, I bid you come with me if you wish to see the wonders of the earth; to know its story; to have some understanding of the great drama of creation, and learn to read the language of the rocks. Having learned this language, you may live in retrospective imagination through the geologic ages. But bring with you every means at your disposal that will aid your understanding.

Bring your knowledge of physics and chemistry, in order to understand how the oceans were formed and how the mountains were raised. The wisest physicists have tried and are still trying their skill on the great earth problems.

Bring your logic and give all your powers of reason full scope. You will need them all.

Bring your knowledge of zoölogy and of botany and in its light trace the path of progress by which living organisms found their way from lower to higher forms, the offspring ever improving on the parent stock.

Bring all your skill in literary expression and exercise it in describing the beauty and grandeur of the earth.

Bring imagination, by means of whose telescopic powers you may explore regions where knowledge has not yet entered.

An Elixir of Life

From the days of Ponce de Leon and his search for the spring of perpetual youth to the present time, men have desired long life. Let me prescribe an elixir by which you may live a million years.

Search out an understanding of the earth with all the helps just mentioned and by their aid live through the misty ages so long gone that reason staggers in evaluating their duration. Although you cannot number the uncounted periods of time or measure the unmeasured ages through which the earth has passed, you can, in imagination, live through some of those ages and enjoy the kaleidoscopic changes by which the planet on which you live has reached its present state of perfection.

In imagination you may witness the collision of stars in their uncharted course and see, as it were, the dust of their impact scattered in the heavens. You may see the star dust gather into worlds and the worlds organize themselves into systems. From seeming chaos you may see the great blazing sun travel from some unknown region of boundless space toward some other unknown region, accompanied by his orderly, obedient followers, the planets.

You may, in imagination, see the earth grow from an in conspicuous globe scarcely larger than its numerous neighbors to a masterful body which has gathered to itself most of these neighbors and incorporated them into a compact symmetrical mass. In this welding of parts, who may say what wars of the elements were waged? But out of the conflict of forces came order and symmetry of form. And out of the hidden laboratories within the earth came the oceans of water and the protecting cloak of the atmosphere without which no living form could exist.

Following still the path of imagination, behold the rise of living beings from simple, minute unicellular forms developing slowly, on the one hand, into plants, and on the other, into animals. Follow these in imagination from age to age and note how each period was characterized by its own peculiar forms of plants and animals, each group adapting itself to the physical conditions of its own time.

The Earth's Activities

There was an age when the furnaces of Vulcan belched fire from many a vent and poured out molten rock in great seething floods. An age followed during which these tumultuous floods of lava, now cold and hard, were covered with water and myriads of sea animals contributed their shells as records of conditions ever changing with the march of time.

At times the climate was warm, and tropical plants grew almost from pole to pole. At other times, the same regions were covered with great sheets of ice, which slowly but irresistibly moved over the surface from the cold poles to the warmer zones, smoothing the country and grinding the surface rocks to powder.

Following still further the path of imagination, behold the forests of bygone days collecting carbon and storing it in the swamps for preservation in beds of coal.

With mental vision, see the minute plants and animals on the land and in the sea gathering the carbon and the hydrogen and each, in its tiny laboratory, molding hydrocarbons of infinite variety destined to be gathered in great rock reservoirs in the form of oil and gas.

In brief, if you properly use the geologic elixir of life, you may see in imagination those processes, operating throughout the ages, by which the earth was stored with ten thousand useful substances and decorated with unnumbered charms.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

stories_in_stone/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 31-Dec-2009