Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

|

FORT STEILACOOM Washington |

|

| ||

This fort was activated in 1849 at the southern end of Puget Sound, 6 miles from the original site of Fort Nisqually, the Hudson's Bay Co. farming center. The latter, which the Indians had attacked earlier in the year, was the nucleus of settlement in the area. During the Indian uprisings in western Washington in 1855-56 that culminated in an assault on Seattle, warriors attacked and almost captured the fort, the major operational base during the uprisings. The Army abandoned it in 1868, and 6 years later Washington Territory gained possession of part of the military reservation.

Western State Hospital, a psychiatric institution, now occupies the site. Four of the officers' quarters have survived, serving today as doctors' residences.

|

FORT WALLA WALLA Washington |

|

| ||

Soldiers from this fort took part in most of the Indian wars of the Northwest: the 1858 campaign in eastern Washington, the Modoc War (1872-73), the Nez Perce War (1877), and the Bannock War (1878). First situated north of Mill Creek and in the spring of 1858 moved southward 1-1/2 miles to its present location, Fort Walla Walla (1856-1911) was founded during a series of Indian outbreaks about 30 miles east of the Hudson's Bay Co. trading post of the same name. In 1855 most of the tribes of Washington had ceded the majority of their lands to the U.S. Government, retaining only enough for reservations. But the subsequent influx of miners and settlers inflamed them, as did reports of U.S. Government plans to construct a railroad from the Missouri River to the Columbia. The coastal tribes went on the warpath in 1855-56, attacking Seattle before being pacified. Some of the tribes of central Washington expressed their aggressions in the Yakima War (1855-56).

|

| Fort Walla Walla in 1857, at its first location. Drawing by Edward Del Girardin. (National Archives) |

Two years later the Spokans, Coeur d'Alenes, and the Palouses of eastern Washington, irritated by a trickle of miners moving to the Colville mining district in 1855-56, began what is sometimes called the Spokane, or Coeur d'Alene, War (1858) by defeating Maj. Edward J. Steptoe's force from Fort Walla Walla near present Rosalia, Wash. Fort Walla Walla subsequently became Col. George Wright's base, supported by Fort Simcoe. In September he won major victories in the Battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plain, Wash. That same fall the opening of the Walla Walla Valley to settlement created new friction with the Indians, and the garrison kept busy maintaining the peace. Beginning the next year and until 1862, it also helped protect crews constructing the Mullan Road.

Numerous historic buildings remain amid modern structures. They are in excellent condition, though the Veterans' Administration has modified many of them. Rows of officers' quarters and barracks run along opposite sides of the parade ground. To the rear of the barracks are the stables. The post cemetery, where military burials from the Nez Perce War are consolidated, is within a city park, immediately south of the hospital. The Daughters of the American Revolution has placed a marker at the first site of the fort, on Main Street between First Avenue and Spokane Street.

|

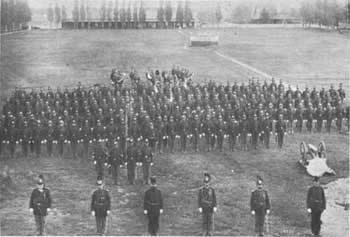

| Second Cavalry troops on parade in 1887 at Fort Walla Walla. (National Archives) |

|

FOUR LAKES BATTLEFIELD Washington |

|

| ||

The clash at this site on September 1, 1858, marked the beginning of a running engagement that culminated 4 days later in the Battle of Spokane Plain. In these battles, Col. George Wright revenged the victory of the Spokans, Palouses, and Coeur d'Alenes of eastern Washington over Major Steptoe in May about 25 miles to the southeast of the Four Lakes Battlefield. Wright's 600 cavalry men and infantry men, equipped with the new 1855 long-range rifle-muskets, whipped an equal-sized Indian force, emboldened by its triumph over Steptoe. The troops, who did not have a single casualty, killed 60 Indians and wounded many others.

An arrow-shaped stone pyramid in the town of Four Lakes marks the site of the battle.

|

SPOKANE PLAIN BATTLEFIELD Washington |

|

| ||

In the wake of the Battle of Four Lakes, the Battle of Spokane Plain was the last in Colonel Wright's 1858 campaign in eastern Washington. Ranging over 25 miles and testing the endurance of the participants, it resulted in another Army victory. After the battle, shrugging off peace overtures, Wright marched through Indian country singling out the fomentors of the war and destroying the horseherds. The Yakima chieftain Kamiakin again made good his escape. But, before returning to Fort Walla Walla, Wright hanged 15 war leaders and placed others in chains. Like the Rogue River Indians of Oregon, the tribes he campaigned against in 1858 never again tried to stem the flow of settlers by force of arms.

A large stone pyramid in a 1-acre State park commemorates the battle.

|

| Gustav Sohon's drawing of the Battle of Spokane Plain. (Smithsonian Institution) |

|

STEPTOE BATTLEFIELD Washington |

|

| ||

The 1858 campaign against the Indians of eastern Washington that culminated in Army victories in September in the Battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plain began at this site. On May 18 about 1,000 Spokans, Coeur d'Alenes, and Palouses attacked Maj. Edward J. Steptoe and his force of 164 men, who were investigating reported Indian depredations and seeking to awe the Indians on a march from Fort Walla Walla, Wash., to the Colville mining district. Severe fighting lasted all day. During the night, Steptoe broke contact and made a forced 85-mile march from the knoll on which he had taken refuge to the Snake River, where some friendly Nez Perces helped the troops cross and find safety on the other side.

The knoll is commemorated by a 4-acre State memorial park. It features a 25-foot granite shaft erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution, which deeded the site to the State. Listed on the shaft are the names of the soldiers who lost their lives and the Nez Perces who aided the retreating troops. The running battle took place in Pine Creek Valley for a distance of 4 miles up stream to the north from the knoll. Except for agricultural use, the landscape is little altered. On the basis of a mistaken identification with Steptoe Butte, a natural landmark about 30 miles to the south, Steptoe Battlefield is sometimes incorrectly called Steptoe Butte Battlefield.

|

| The 1858 Steptoe disaster, pictured here by Gustav Sohon, spurred Army retaliation. (Library of Congress) |

|

TSHIMAKAIN MISSION Washington |

|

| ||

In 1838 the interdenominational American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent a small group of reinforcements to join Dr. Marcus Whitman and Rev. Henry H. Spalding in the Oregon country. Part of the group were two Congregational ministers and their wives: Elkanah and Mary Walker and Cushing and Myra Eells. After spending the winter at Whitman Mission, Walker and Eells moved north in the spring of 1839, and at a site in a pleasant valley north of the Spokane River that the Spokan Indians called Tshimakain ("Place of the Springs") established a mission. About 25 miles northwest of the site of the city of Spokane, it was the farthest north of the American Board establishments. Its nearest non-Indian neighbors were at the Hudson's Bay Co. post of Fort Colville, 50 miles farther north. The missionaries had only limited success with the Spokans. When the Cayuses attacked Whitman Mission in the fall of 1847, the Walkers and Eellses fled to Fort Colville and in the spring of 1848 to the Willamette Valley. Tshimakain Mission never reopened.

|

| Tshimakain Mission in 1853. Tinted lithograph by John Mix Stanley. (Bancroft Library, University of California) |

No remains have survived, and a modern farmhouse occupies the site. The spring that provided the missionaries with water still flows through the farmyard. A State marker stands on the east side of Wash. 231 directly in front of the site. The valley itself is virtually unchanged except for occasional fences.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/sitec18.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005