|

Historical Background

The close of the Civil War released America's

energies to the westward movement. Thousands of emigrants and settlers

pushed into the Indian domain with scant regard for the sanctity of

hunting grounds or treaty agreements. Railroads supplanted the trails.

The Union Pacific and Central Pacific, joined in 1869, were succeeded to

the north and south by other transcontinental railroads, and a network

of feeder lines reached into many remote corners of the West. Miners

spread up and down the mountain chains of Colorado, Montana, Idaho,

Nevada, and Arizona. Steamers, sailing up the Missouri River, carried

passengers and freight to Fort Benton, Mont., for the land journey to

the gold mines of western Montana. Stockmen moved onto the grasslands.

Dirt farmers, attracted by the liberal provisions of the Homestead Act

of 1862, followed. Towns and cities sprang up everywhere. The once huge

herds of buffalo dwindled to the brink of extinction, a process hastened

by professional hunters interested only in the hides. Other game

diminished similarly. Forts multiplied, and the soldiers came back in

numbers unprecedented before the war. In a matter of two decades, 1865

to 1885, the Indian was progressively denied the two things essential to

his traditional way of life—land and game. Often he fought back,

and this period of history featured the last—and most

intense—of the wars between the United States and its aboriginal

peoples.

|

|

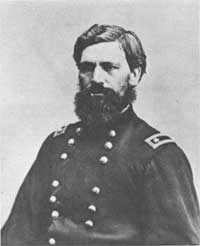

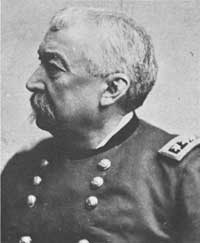

| Gen. George Crook. (Library of Congress) |

Gen. Nelson A. Miles. (National Park Service) |

|

|

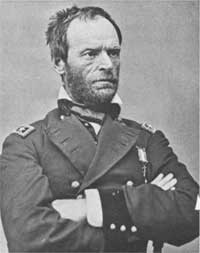

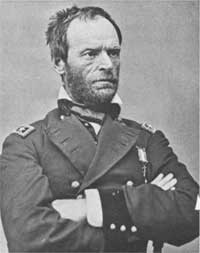

| Gen. William T. Sherman. (National Archives) |

Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. (National Archives) |

|

|

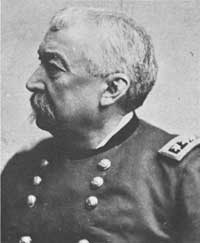

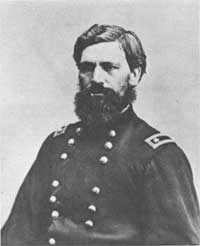

| Gen. Oliver O. Howard. (Library of Congress) |

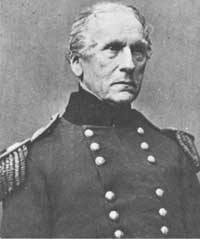

Gen. William S. Harney. (National Archives) |

|

|

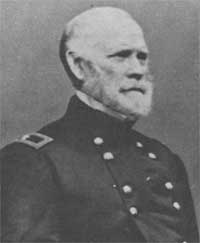

| Gen. Winfield S. Hancock. (Library of Congress) |

Gen. John E. Wool. (National Archives) |

Nearly continuous hostilities swept the Great Plains

for more than a decade after the Civil War as the flow of travelers, the

advance of the railroads, and the spread of settlement ate into the

traditional ranges of the Plains tribes. Red Cloud led the Sioux in

opposing the Bozeman Trail, a new emigrant road that cut through their

Powder River hunting domain to the Montana goldfields. The Army

strengthened Fort Reno and erected Forts Phil Kearny and C. F. Smith

along the trail but could not provide security. In December 1866 the

Sioux wiped out an 80-man force from Fort Phil Kearny under Capt.

William J. Fetterman. They tried to triumph again the following August

but in the Wagon Box and Hayfield Fights were beaten back. When the

Union Pacific Railroad reached far enough west to provide another route

to Montana, in the Fort Laramie Treaty (1868) the Government reluctantly

yielded to the Sioux and withdrew from the Bozeman Trail. To the south,

in Kansas, Gen. Winfield S. Hancock led an abortive expedition against

the Cheyennes and Arapahos in 1867 and, instead of pacifying, aroused a

people who had not yet forgotten Sand Creek. Kiowas and Comanches

continued to terrorize the Texas frontier.

|

| Peace commissioners meeting at

Fort Laramie, Wyo., with Sioux chiefs. The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

brought temporary peace on the northern Plains—until miners invaded

the Black Hills in 1874-75. (National Archives) |

|

| Charles M. Russell's "Indian

Hunters Return" portrays winter life among the Indians. Recognizing

their immobility and vulnerability at that time of the year, Gen. Philip

H. Sheridan launched a hard-hitting winter campaign in 1868-69.

(Montana Historical Society) |

Despite the Medicine Lodge Treaties of 1867, which

were de signed to bring peace to the southern Plains, war broke out once

more in August 1868. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan organized a winter

campaign, in which columns converged on Indian Territory from three

directions. One, under Lt. Col. George A. Custer, struck the Cheyenne

camp of Black Kettle—the same chief who had suffered so grievously

at Sand Creek 4 years earlier. At the Battle of the Washita, November

27, 1868, Custer decimated the band. Black Kettle fell in the first

charge. On Christmas Day another of the commands, under Maj. Andrew W.

Evans, attacked a Comanche camp at Soldier Spring, on the north fork of

the Red River. Custer, Evans, and Maj. Eugene A. Carr, leader of the

third column, demonstrated that the Army could operate during the winter

months, when the Indian was most vulnerable. Most of the tribes yielded

and gathered at newly established agencies in Indian Territory. The

Battle of Summit Springs, Colo., the following July brought the last

holdouts to terms.

|

| In the Battle of the Washita,

Okla., and in other instances the Army surprised the Indians by

attacking their sleeping villages at dawn. Such an attack is portrayed

in Charles Schreyvogel's "Attack at Dawn." (Gilcrease

Institute of American History and Art) |

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro6.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005

|