Historical Background

On the northern Plains, serious trouble with the Sioux broke out in 1854 when a young Army officer at Fort Laramie converted a minor incident into a major confrontation. He and his detachment were annihilated. The Army responded with a sharp campaign in 1855-56. Gen. William S. Harney's attack on a Sioux village at the Battle of Blue Water and subsequent march through the Sioux homeland restored an uneasy calm to the Oregon-California Trail. On the southern Plains the Cheyennes, provoked by traffic on the Smoky Hill Trail to newly discovered mines in the Rocky Mountains, brought on a similar response from Col. Edwin V. Sumner in 1857.

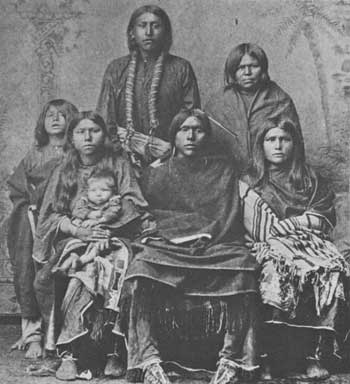

|

| Comanche family. Fierce, warlike, and expert horse men, the Comanches won the epithet of "Lords of the South Plains." Following the Great Comanche War Trail, they terrorized the southern Plains and northern Mexico. (National Archives) |

Kiowas and Comanches occasionally harassed the Santa Fe Trail, but they directed their principal aggressions at the Texas frontier. The Army established an elaborate defense system to deflect these raids. It erected two lines of posts extending from the Red River to the Rio Grande, a third down the Rio Grande to the Gulf of Mexico, and a fourth along the road from San Antonio to El Paso. Neither the forts nor offensive operations north of the Red River in the years 1858-60 noticeably diminished the destruction. These Indians had raided the Texas frontier and deep into Mexico for a century; raids were a basic economic and social pursuit, difficult to replace and not lightly surrendered.

Similarly, Apaches, Navajos, and Utes had plagued the Rio Grande settlements of New Mexico since the earliest years of Spanish rule. Now, because of the growing competition with settlers for the meager agricultural and game resources of the region, they had still greater incentive. The new network of forts disturbed the routine only slightly. Military offensives against the Utes and Jicarilla Apaches in 1854 and 1855 neutralized the menace from the north. But similar campaigns between 1857 and 1861 against the Gila and the Western Apaches in the south and the Navajos to the west gave no relief to the settlements.

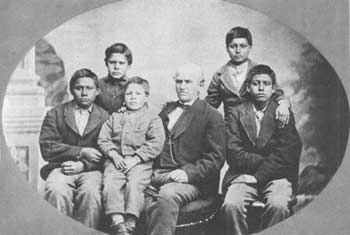

|

| Captives and plunder lured Kiowa and Comanche raiders. Quaker Indian Agent Lawrie Tatum poses at Fort Sill, Okla., about 1872 with a group of freed Mexican children. (Smithsonian Institution) |

On the Pacific coast, a large population of semisedentary Indians occupied the rich mountains that had set off the California gold rush. Overrun by miners, some groups simply disappeared—if they were not exterminated, scattered, and destroyed as identifiable cultural entities. Others, principally in northern California and southern Oregon, fought back. In a succession of so-called "Rogue River Wars" between 1850 and 1856, the Army crushed them and placed the survivors on reservations.

North of the Columbia, in present Washington, the chieftain Kamiakin in 1855-56 briefly united the Yakima and allied tribes east of the North Cascade Mountains with Puget Sound groups to the west. The Yakimas were angered by an invasion of their lands by gold seekers headed for the newly discovered Colville diggings, and all resented land-cession treaties recently thrust upon them. As in California and Oregon, the operations of Regular and Volunteer troops, commanded by Gen. John E. Wool and Col. George Wright, ended organized resistance. The disaffection, however, spread eastward to the Spokan, Palouse, Walla Walla, and associated tribes. After a combined army of warriors mauled a command under Lt. Col. Edward J. Steptoe in the spring of 1858, Colonel Wright set forth at the head of a formidable column. He won clear victories at the Battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plain in September, and in subsequent negotiations brought the war to a close.

|

|

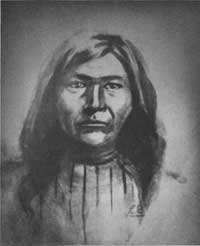

| Red Cloud, Ogalala Sioux. (photo by Charles M. Bell, Smithsonian Institution) | Geronimo, Chiricahua Apache. (photo by A. Frank Randall, Smithsonian Institution) |

|

|

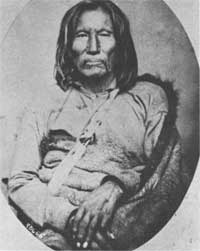

| Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa Sioux. (photo by David F. Barry, Smithsonian Institution) | Victorio, Warm Springs Apache. (Musuem of New Mexico) |

|

|

| Satank, Kiowa. (photo by William S. Soule, National Archives) | Satanta, Kiowa. (photo by William S. Soule, Smithsonian Institution) |

|

|

| Big Tree, Kiowa. (photo by William S. Soule, National Archives) | Joseph, Nez Perce. (National Archives) |

Except for the tribes of California and the Pacific Northwest, the pressures of the 1850's did not fundamentally disturb the bulk of the western Indians. The forts represented a permanent encroachment on their domain. So did the handful of mining camps that appeared in the intermountain West toward the close of the decade. But soldiers and miners produced only local disruptions, causing but slight shifts in tribal ranges and alliances. Even the military campaigns—again excepting those in the Northwest-proved mainly an annoyance. They demanded constant vigilance, occasional flight, and, rarely, a skirmish or battle that involved loss of life and property. This was nothing new to a people who had always regarded intertribal warfare as a condition of life. Growing numbers of trading posts represented an encroachment, too, but as an integral part of Indian life for almost half a century they were not regarded with antagonism.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro3.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005