|

Vanguard of Expansion

Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819-1879 |

Chapter VIII

THE GREAT SURVEYS AND THE END OF AN ERA

The trans-Mississippi West to which the Engineers returned after the Civil War was vastly different from the wilderness of Major Long's time. The nation stretched westward to the Pacific, and from San Diego to Puget Sound. Towns like Omaha, Denver, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco, all destined to be large cities, grew rapidly while work parties laid track for a trans-continental railroad across the central plains, the Great Basin, and the Sierra Nevada, The clang of a hammer striking a ceremonial golden spike at Promontory, Utah, on 10 May 1869, marked the completion of the first railway to the Pacific and heralded the passing of the frontier.

The increase in western population, from about two million in 1850 to nearly seven million in 1870, brought on the climactic Indian wars of the post-Civil War decade. Tribal leaders, among them the Apache Victorio and Crazy Horse of the Oglalas, organized last, desperate efforts to preserve the autonomy and lands of their peoples. In the ranks of the blue-clad vanguard of settlement that won these wars were Engineer officers, men like Captains William J. Twining and David P. Heap, providing field commanders with maps and accompanying columns into battle. [1]

Along with the dramatic increase in western population came scientific and educational developments that defined a new era for the Engineers. Education in the sciences and engineering, once virtually the exclusive domain of the Military Academy, became available at a number of fine institutions, among them Yale's Sheffield Scientific School, the Lawrence School at Harvard, and Dartmouth's Chandler School. Frequently employing West Point graduates and curricula, these colleges made technical education available to a growing number of civilian students. The second development, the growing specialization in the sciences, was closely related to the first. Lacking a commitment to the training of military officers, the new schools could become centers for the development of such specialties as geology and paleontology. While West Pointers learned the rudiments of many fields, civilian institutions produced scientific experts and specialists. [2]

By allowing fledgling scholars to accompany western expeditions, the Engineers had encouraged the development of civilian specialists. Themselves once the students of the lone trappers and traders who first probed the mysteries of the new country, Engineer explorers soon became the teachers of others, giving young scientists like Ferdinand V. Hayden and John S. Newberry the opportunity to study frontier regions and mature in their disciplines. By the time of the great surveys—systematic postwar examinations of western resources made necessary by the rapid growth of the region—western investigation had moved through the eras of the mountainman and the officer-explorer. An era of civilian dominance was on the horizon.

|

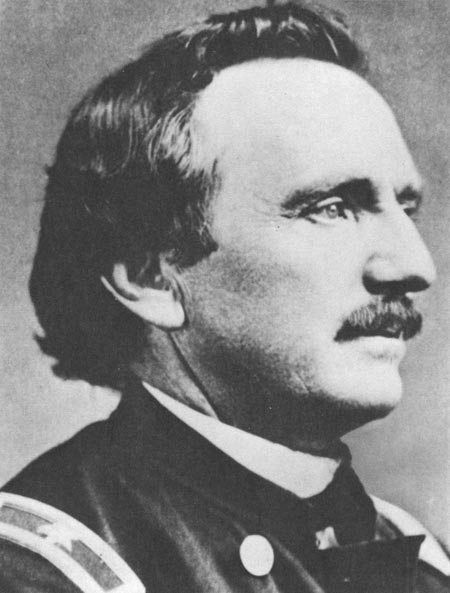

| William F. Raynolds. National Archives. |

Although sponsored by the Corps of Engineers, the first of the great surveys was led by a civilian, Clarence King. A masterful raconteur and close friend to Henry Adams, King graduated from the Sheffield School before gaining his first extensive field experience with Professor J. D. Whitney's California state geological survey. While working with Whitney, King conceived his plan for a federally-funded geological inquiry into the structure and mineral deposits of the country along the route of the transcontinental railroad. With the support of former Engineer explorer Colonel Robert S. Williamson, Spencer Baird, and California Senator John Conness, King went to Washington with his plan for a geological examination of a 100-mile-wide strip along the fortieth parallel line of the Union Pacific—Central Pacific railroads from eastern Wyoming to the California-Nevada border. After securing the sponsorship of Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys, the Chief of Engineers, King persuaded Congress to provide funds, Then he organized the expedition, selected his personnel, and set out from New York to begin work on the first of the great surveys. [3]

At the head of his United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, King started in 1867 on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada and worked his way eastward across the Great Basin to the Wasatch range. Although his main purpose was a thorough geological analysis, he also made detailed topographical maps. Military explorers had separated knowledge of the Basin from myth and identified its features fairly well, but their maps were not sufficiently detailed to fix the locations of excavations and mineral deposits. So, while King's field parties studied the subsurface secrets of the Great Basin, they established a continuous system of triangulation across Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming to determine trigonometrically the location of important topographical features. [4]

In the deserts and canyonlands of the Great Basin, King examined a "pretty full exposure" of the earth's crust that took in all the broad divisions of geological time. Working from the notion of zonal parallelism, first suggested by geologist William P. Blake, King observed that metal deposits occurred in parallel, longitudinal zones that followed the same patterns as the western mountain ranges. For example, a gold belt existed through the mountains that ran north from New Mexico, through Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana. Farther west, parallel to a line of mountains through western New Mexico, Utah, and western Wyoming, lay a zone of silver-bearing lodes. All the way to the Pacific-coast ranges that King had examined with Whitney, most of the parallel zones also occurred in the same geological layers. With these discoveries, King's survey made significant strides in the identification of mineral deposits, their location, and history. [5]

While completing his fieldwork in 1872, King began to hear rumors of spectacular deposits of precious stones in the Green River basin. The story, spread by two miners who mysteriously appeared at the office of a San Francisco banker with a bag of rubies and diamonds, was too important to ignore. If the stones actually existed in an area which King claimed to have thoroughly studied, the credibility of his survey would be destroyed. If, on the other hand, the claims amounted to a spectacular hoax, they had to be exposed. With the San Francisco and New York Mining Commercial Company already organized and stocks shortly to be offered to the public, King returned to northwestern Colorado to hunt for diamonds.

|

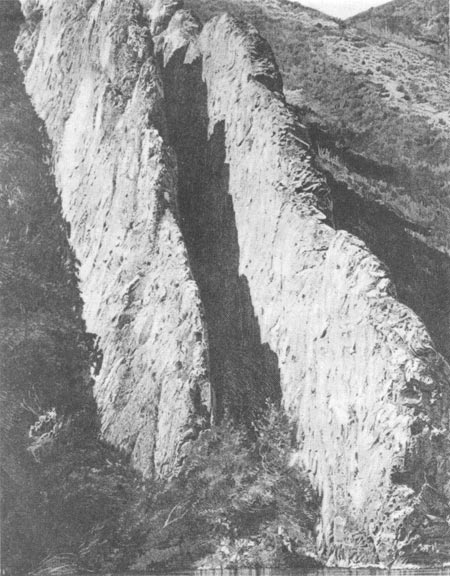

| Devil's Slide, Weber Canyon, Utah. |

Back on the windswept tableland south of Fort Bridger, King and a handful of associates undertook the implausible quest. After a brief search a ruby was discovered, then several more, and finally three diamonds. With a handful of gemstones after a single day's work, all were believers. On the second day, the King party found an even larger number of diamonds and rubies, all but one just below the surface. The exceptional gem, sitting precariously on a rock, suggested an extraordinary origin for the treasure. Before the day ended, the fraud was obvious. Amethysts, emeralds, sapphires, garnets, rubies and diamonds, an unheard-of combination in nature, were unearthed, but only where the ground had been disturbed. King hastened to San Francisco, where he revealed the swindle just in time to prevent the sale of $12 million in stock. Exposure of the diamond hoax, as great a fraud as ever concocted in the get-rich-quick West, brought him national acclaim and established the practical value of his survey. [6] "Let it not be said," wrote the editor of a mining journal, "that geological surveys are useless. . . . This one act has certainly paid for the survey of the 40th Parallel and has brought deserved credit to Mr. King and his assistants." [7]

King's seven-volume report of his exploration was a scientific best seller. Fielding B. Meek, one of the country's leading paleontologists, wrote the section on fossils, and Robert Ridgway of the Smithsonian classified the birds with Baird's assistance, In addition, Professor Othnie C. Marsh of Yale prepared a volume on extinct toothed birds, King himself worked on two important volumes, Systematic Geology and Mining Industry. The latter, written by James D. Hague and King, quickly became very popular. Scientific critics gave it lavish praise, and the American Journal of Science considered it the most important contribution to the literature of mining to date. Requests for copies greatly exceeded the number printed. King's other volume, Systematic Geology, also received favorable notice. Henry Adams, writing in The Nation, even recommended publication of an inexpensive edition for use in technological schools. The exploration of the fortieth parallel was a great success and a personal triumph for the young geologist who led it. [8]

|

| One of King's survey teams at Shoshone Falls of the Snake River. National Archives. |

King was still in the field when two other surveys, one under John Wesley Powell and the other under Ferdinand Hayden, began operations. At the head of the United States Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, Powell concentrated his efforts on the lands bordering the Green and Colorado rivers, while Hayden's United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories toiled in western Kansas and Colorado. Operating under the auspices of the Interior Department, these surveys shared two basic characteristics with King's Corps-sponsored enterprise: they were led and staffed by civilians and they concentrated on geology. [9]

With the proliferation of civilian surveys plainly threatening an important peacetime function of the Army, General Humphreys authorized Lieutenant George M. Wheeler to organize the United States Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian. An 1866 graduate of the Military Academy who married into the prestigious family of Montgomery and Preston Blair, Wheeler developed the plan for a systematic topographical survey while assigned to Brigadier General Edward O. C. Ord's Department of California. His work with Ord included a difficult reconnaissance through southeastern Nevada and western Utah, during which he made the first north-south crossing of the Great Basin since the days of the early mountainmen. Wheeler knew that western military commanders, particularly Lieutenant Colonel George Crook, who was about to begin his campaigns against the Apaches, needed detailed topographical maps. Humphreys, anxious to obtain maps that would be useful to Crook and other commanders as well as to recover for the Corps its preeminence in western exploration, agreed to Wheeler's proposal. [10]

Part precise astronomy and part detailed topography, Wheeler's first expedition in 1871 was also part showmanship. With an eye to his competition with the other surveys for popularity and funds, he asked the editors of a popular New York magazine, Appleton's Journal, to send a reporter to accompany him. The magazine gave the assignment to Frederick W. Loring, a 22-year-old Harvard graduate, considered "the most promising of all the young authors of America" by English novelist Charles Reade. [11] Photographer Timothy O'Sullivan, a former assistant of renowned Civil War photographer Mathew Brady and one-time employee of Clarence King, also joined Wheeler. Young Loring, the first reporter to accompany a western exploration, and the experienced O'Sullivan gave Wheeler a formidable publicity department. [12]

The 1871 effort should have provided ample grist for Wheeler's publicity mill. His party crossed the already legendary Death Valley, which was first traversed by several parties of struggling forty-niners. [13] Although three men were felled by the 120° heat, they completed the daring trek safely, and Appleton's readers saw the following account of the desert:

Its heat is its greatest terror, for there is abundance of water in the canyons which open into its western side, so that thirst is to be feared more from the concealment than the scarcity of the springs. But its beauty is evil, and, though it is picturesque, it is frightful. I trust I may never have to pass through it again. [14]

The journey through Death Valley yielded important results, a map and detailed information on the location of water, but the ascent of the Colorado later in the season was superfluous. Lieutenant Ives had already gone up the great river to the head of navigation, and Powell had come downstream from the Green. Wheeler paid dearly for the unnecessary journey. When one of the party's three flat-bottomed boats overturned in October, at a place Wheeler named Disaster Rapids, he lost his notes and natural history collection. [15] His impetuosity and publicity-consciousness seriously diminished the results of his first season's work.

|

| A canyon in the Uinta Mountains of Colorado. |

|

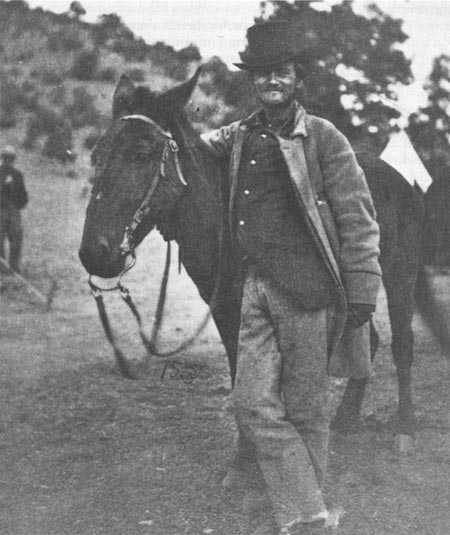

| Frederick W. Loring. National Archives. |

The entire party survived the hair-raising incident, but the greatest tragedy was yet to come. Accompanied by two members of the survey team, William Salmon and P. W. Hamel, journalist Loring left the party for California to report the adventures on the Colorado. He got no farther than Wickenburg, Arizona. A band of Apaches ambushed the stagecoach and killed six of the eight passengers, including Loring and his two comrades. [16]

Loring's death at the hands of the Apaches, soon followed by another defeat on the publicity front when O'Sullivan lost most of his negatives, had a great impact on Wheeler. The government's Indian policy, a benign but misguided attempt to make farmers out of warrior-hunters, seemed to Wheeler to be completely in error. Unsympathetic toward Indians or "that class of well-intentioned but illy-informed citizens who claim that the Indians are a much-abused race," he believed the Indian question in Arizona could only be settled by thoroughly defeating and subduing the Apaches. [17] His published view of Indians as irredeemable savages lent credence to unproved charges that he tortured several of them to extract information. [18] His attitude also influenced his methods. In 1875, one of his parties ransacked an Indian burial ground near Santa Barbara, California, and sent two hundred skulls east to be studied at Harvard and housed in the Smithsonian. While Wheeler's attitudes and methods were far from unique, they angered many, including fellow explorer Powell who had established a rapport with the Indians of the Colorado River region. [19] Ironically, the effort to obtain favorable publicity through Loring ultimately backfired.

|

| The start of Lieutenant Wheeler's 1871 ascent of the Colorado. |

Although Wheeler understood from the outset that "the day of the pathfinder has sensibly ended in this country," he knew the old ground still required systematic study to blend the old routes of exploration into a coherent topographical picture. [20] And working over the terrain still involved extremely hard work. As Wheeler noted in his comments on his parties in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, "labors in this field become exploration indeed, and hardship, fatigue, with now and then scarcity of supplies and danger from hostile Indians, falls to the lot of those who are chosen for the task...." [21] In spite of the difficulties, the Wheeler parties covered much more ground than all the other surveys. They examined almost all the territory south of King's fortieth parallel expedition that lay between California and the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

Wheeler's personnel performed this remarkable feat divided into numerous small parties. In 1874, for example, the survey worked in nine divisions, six under Army officers, two under Army surgeons, and one led by a civilian scientist. The sixteen lieutenants, usually Engineers, who assisted Wheeler between 1871 and 1879 included three who graduated at the head of their West Point classes—Eric Bergland (1869), Rogers Birnie, Jr. (1872), and Thomas W. Symons (1874). [22]

Although junior officers commanded most of the field parties, the expeditions were staffed by many illustrious men of science. Henry C. Yarrow, an Army surgeon who spent several years in the field with Wheeler as a zoologist, later became the Smithsonian's first curator of reptiles. Between 1878 and 1889 Yarrow donated his talents to the museum while pursuing his career as a military physician. Professor Edward D. Cope also aided Wheeler by collecting and evaluating minerals and fossils, while conducting one of the bitterest feuds in the annals of American science with arch-rival Othniel C. Marsh. The brilliant geologist Grove Karl Gilbert got his first western field experience with the 1871 expedition before joining the Powell survey two years later. [23]

During his first years in the field, Wheeler gradually refined his techniques and procedures. In 1873 the three divisions of his survey, led by Wheeler and Engineer Lieutenants William Marshall and Richard L. Hoxie, examined 72,500 square miles of terrain in four states and territories. Hoxie, operating in the Utah canyonlands, took readings at nearly 1,500 topographical and triangulation stations and measured over one thousand miles of meander lines. Each night he and topographer Gilbert Thompson, once an enlisted soldier in the Engineer Battalion, computed the latitude of their position, drew their meander-line profiles of the terrain, and recorded principal topographic features. While Hoxie mapped nearly 6,000 square miles of what he called "a very difficult mountain and canyon country," Wheeler in Arizona and New Mexico and Marshall in Colorado performed similar duties. [24]

|

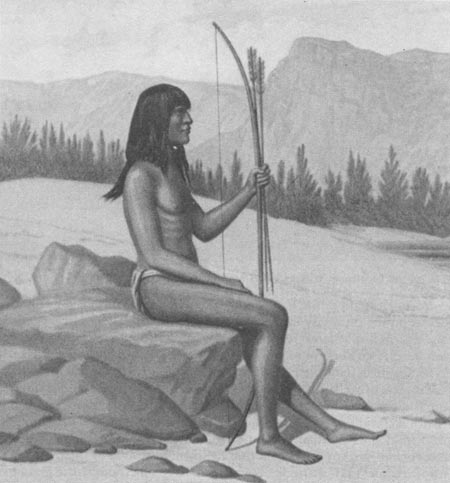

| One of the Mohave Indians who accompanied Wheeler in 1871. |

While in South Park west of the Front range of the Colorado Rockies, Marshall confronted a strange and unexpected problem. About the same time that he entered the area, one of the Hayden parties arrived. Eventually four of Hayden's five field divisions came on the scene. Leaders of both surveys claimed the right to examine the park, and neither side relented. So both set up their instruments on the same mountains and went about their redundant business. [25] When this ridiculous state of affairs came to the attention of Congress, an investigation became inevitable.

While the congressional investigation of 1874 settled nothing, it revealed a great deal. Hayden, disliked by even his former teacher Newberry as "so much a fraud that he has lost the sympathy and respect of the scientific men of the country," [26] threatened to use the influence he had carefully built by hiring the relatives of political patrons and distributing collections of western photographs to destroy Wheeler. [27] Powell assailed Wheeler before the House Committee on Public Lands, selecting the worst example of the lieutenant's work to assert that all his maps were worthless for geologists. King, beholden to the Corps for sponsoring his survey, kept his own counsel, but the rest of the civilian scientific community, with much to gain from the elimination of military competition, supported Hayden and Powell. Nearly all of the scientists were convinced that civilian schools had surpassed the Military Academy in training personnel for precise surveys. Those who had worked for the Army also resented the constraints of military supervision, particularly the requirements for frequent reports. Although the investigation began as an inquiry into duplication and waste, the issue crystallized as civilian versus military control of western exploration. Reprieved only by the backing of President Grant, Wheeler knew his survey's days were numbered. [28]

|

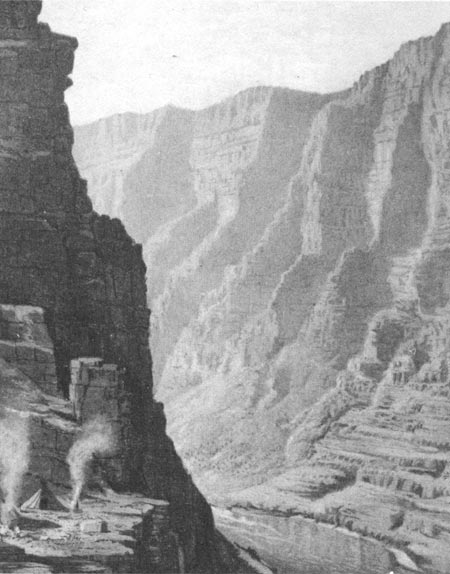

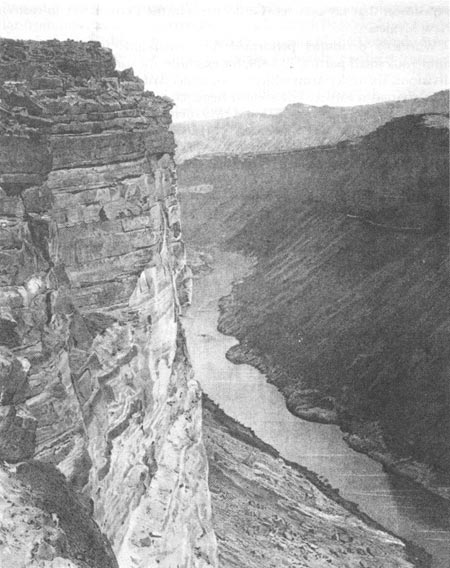

| The Grand Canyon of the Colorado, near Paria Creek, looking east. |

The consolidation issue remained unresolved while Wheeler continued his fieldwork. In the mid-1870's, his parties examined contiguous north-south strips, carefully recording their topographical findings. Divisions of the survey ranged far and wide, from the Sangre de Cristo range in southern Colorado in 1875, to Lake Tahoe, one of the crowning beauties of the Sierra, in 1876. [29] In 1877 and 1878 parties worked in six different states and territories, integrating their work with surveys performed in earlier years. Aware all the while that his survey was in danger of termination, Wheeler hoped to present the War Department "at as early a date as possible, a complete map of the entire territory." [30]

When Wheeler returned to the field, he also renewed his public relations efforts. Once again he had his reporter, this time William H. Rideing, the author of fifteen books and a contributor to the New York Times, Appleton's, and Harper's. [31] In 1875, the city-bred journalist, attired in a dapper hunting suit, joined the flannel- and buckskin-clad surveyors in Colorado. Although he stayed with Wheeler for two seasons, he never seemed comfortable in the wilderness. Campfires, he once wrote, only reminded him that his back was cold. And the Arizona desert, warm enough to be sure, had its own nuisances, mainly "a thousand crawling things"—rattlesnakes, centipedes, beetles, and lizards. [32] Through it all, Rideing never lost his sense of humor. Staring at a dinner served hastily in a Rocky Mountain cloudburst, he found "a geological sort of mess," which he described with the precision of a Newberry or King:

The upper crust consisted of dried apples, and beneath this was a stratum of baked beans, in which a small fossilized tree in the shape of a pickled cauliflower was imbedded. Exploring further, and with increasing interest, I unearthed some doughy bread permeated with bacon grease, and a teaspoonful of sugar evidently deposited in the wrong place during the confusion of the moment. [33]

While the leaders of all four surveys competed for public funds and published all manner of puffery, from lavishly illustrated books to stereopticon slides, Congress referred the consolidation question to the National Academy of Sciences. The result was a foregone conclusion. The Academy represented the community of civilian professional scientists and could be expected to support its constituents. [34]

|

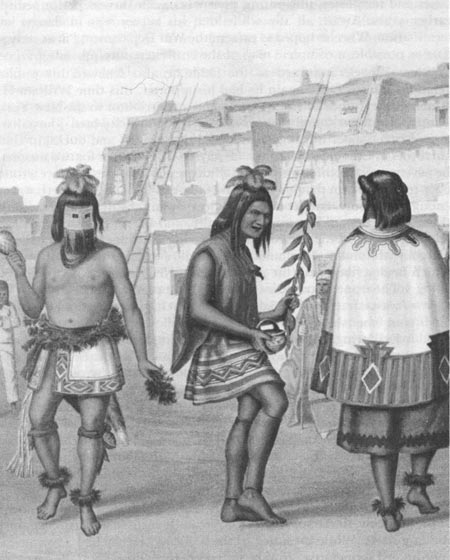

| A sacred dance at the Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, 1878. |

The death of Joseph Henry, secretary of the Smithsonian and president of the academy, in the spring of 1878, virtually insured a decision against the Engineers. While president of the academy, Henry had advocated a coordinated cooperative effort by the competing surveys and the agencies they represented. He had encouraged the academy to study the matter and recommend a solution that might include all the competitors in any consolidation. When Henry died, Professor Marsh became interim president and selected the committee to review the matter for Congress. Marsh's well-known views, shaped by his conviction that military control was restrictive, were also colored by his friendship with Powell and his hostility toward Wheeler's former employee, Professor Cope. Although several members of the academy, including military officers like General Humphreys, supported continued Engineer involvement, Marsh selected the investigating committee with such care that this view went unrepresented. [35]

As expected, the academy report recommended consolidation of the surveys under civilian leadership. The academy proposed establishment of the United States Geological Survey to study the geological structure and economic resources of the public domnain. In 1879, after Congress agreed and appropriated funds for the new agency, Clarence King received the appointment as the survey's first director. With a few exceptions, notably Alaskan exploration, the era of the Engineer-explorer was over. [36]

Although the Wheeler survey was cut short, its results were impressive. Between 1871 and 1879 the various field parties examined and mapped nearly one-fourth of the region west of the one-hundredth meridian. Concentrating on the Southwest, Wheeler studied over two hundred mining districts and 143 mountain ranges. His collectors also accumulated over 61,000 botanical, zoological, geological, and ethnological specimens, many of which were new to science. He contributed most of these to the Smithsonian. These achievements support his own overall assessment of his work as "a permanent contribution to the geography, topography, and natural history of 359,065 square miles of the western portion of the United States." [37]

There are few man-made monumnents to the men who wore the gold braid of topogs or the black trim of Engineers on their uniforms. A stone marker commemorates the massacre of Captain Gunnison and several of his assistants in the summer of 1853. But the names of many of the soldier-explorers remain on the land they helped open, not on monuments. For example, at least six mountains, Whipple, Sitgreaves, and Graham in Arizona; Long's Peak in Colorado; Emory Peak in the Big Bend country of Texas; and Barlow Peak near the Yellowstone, bear the names of Engineers and topogs, Other names—among them Frémont, Gunnison, Nicollet, Raynolds, Stansbury, and Warner—on the valleys, streams, towns, and counties of the trans-Mississippi West are constant reminders of the important contributions Engineers made to western expansion and development.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

schubert/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 17-Mar-2005