|

Vanguard of Expansion

Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819-1879 |

Chapter II

FRÉMONT AND THE SCREAMING EAGLE

The America of 1842 stood poised to become a continental nation. Driven by complementary expansionist visions, the agrarianism of Thomas Jefferson and the commercial-maritime outlook of John Quincy Adams, the nation had already taken huge strides across the Mississippi. [1] As president in 1803, Jefferson obtained the immense but ill-defined Louisiana Territory from financially hard-pressed France. In the next year, he sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark through the new country to the Pacific Ocean, calling the nation's attention to the vast domain and establishing a basis for later claims to ownership of Oregon. Thirteen years after the return of Lewis and Clark, Secretary of State Adams negotiated a treaty with Spain in which the boundaries of Jefferson's purchase were clarified and Spain gave up its claim to the Oregon country. Russian pretensions to Oregon went the way of Spain's after promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine, a creation of Secretary Adams that warned off potential European colonizers. Only Great Britain, which occupied Oregon jointly with the United States, remained a competitor when Adams left the State Department for the presidency in 1829.

Throughout the 1820's and 1830's, Americans made great inroads into the Mexican Southwest and Oregon. The beavermen ranged over the Oregon country and found an agricultural paradise into which farmers and missionaries began to trickle. In the southwest, American traders gained first a foothold and then pre-eminence in the Santa Fe trade. Meanwhile, Texas broke loose from Mexico and sought entry into the Union. As American influence spread, it began to seem that these far-off regions would inevitably fall to the Republic.

In the 1840's the process of expansion rapidly accelerated. When it became plain that Mexico, a weak young nation wracked by internal strife, could not hold its northern provinces for long, anxiety over British and French intervention mounted. At the same time, American appetites were whetted by Commander Charles N. Wilkes's glowing descriptions of the ports of San Francisco and Puget Sound after his naval exploring expedition of 1841. Jeffersonian agrarian expansionists already sang the praises of fertile Oregon, but after the Wilkes expedition Americans with a commercial-maritime orientation also took notice. [2] The nation was no longer willing to wait until the tenuous bonds connecting New Mexico to Mexico, and Oregon to Britain, broke of their own accord.

Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri was among those least inclined to allow nature to take its course. Benton's St. Louis, transformed from a sleepy French outpost to a frontier metropolis at the hub of the Missouri River and Santa Fe trade routes, faced westward to Oregon and New Mexico. As feisty on the Senate floor as he had once been with a dueling pistol, Senator Benton shared his constituents' vision. Eloquently and willfully he turned many of his countrymen's heads in the same direction. While declaring that "man and woman were not more formed for union, by the hand of God, than Texas and the United States are formed for union by the hand of nature," he also called for "thirty or forty thousand American rifles" to negotiate an end to joint occupation of Oregon. [3]

As the long-standing Oregon dispute came to a boil, Benton planned a major expedition under Joseph Nicollet. Aware that each new settler in Oregon strengthened the claims of the United States, Benton wanted the French scientist to examine the emigrant route to the jointly occupied territory. Few risked the long and hazardous journey, and some of those who did perished along the way. To increase the number of emigrants and enhance their chances of success, good maps and descriptive guides were desperately needed. With these ends in mind, Benton secured funds from Congress for an examination of the Oregon Trail.

Because Nicollet's health was failing, Senator Benton offered leadership of the expedition to Lieutenant Frémont. Benton first met Frémont when he and Nicollet came to Washington to complete their report and map. As guests at the home of Ferdinand R. Hassler, chief of the coast survey, the urbane, polished Frenchman and his dashing assistant moved in the best circles and became society favorites. [4] Among the houses they frequented was that of Senator Benton, who took an avid interest in their work. Soon a romance blossomed between Frémont and the Senator's daughter Jessie. In the face of stern opposition from Jessie's parents, including banishment of the young topog to a survey of the Des Moines River, they married secretly. After a burst of senatorial temper came reconciliation. Benton had gained as a son-in-law an experienced explorer who would collaborate in his expansionist scheme.

In May 1842, Frémont bade his wife and his father-in-law farewell and set out on his first major expedition. Although his instructions from Colonel Abert required only a scientific survey of the vast region between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, Frémont knew "the object of this expedition was not merely a survey; beyond that was its bearing on the holding of our territory on the Pacific; and the contingencies involved were large." Benton wanted him to "open the way for the emigration through the mountains," by marking the path and demonstrating the government's support of Oregon-bound settlers. Thus, Frémont's journey would blend scientific exploration with the politics of western expansion. [5]

Before he left Washington, Frémont hired a skilled topographer. Red-faced and red-haired Charles Preuss had burst into the Benton home just before Christmas, 1841, clutching a recommendation from Ferdinand Hassler as an excellent map-maker. Unemployed and desperate to find support for his family, Preuss could only stammer incoherently, but Hassler's note, which advised Frémont to examine some of Preuss's maps, spoke for him. Duly impressed with the German's work, Frémont provided his needy family with Christmas dinner and offered Preuss employment on the still incomplete map of the Mississippi basin, computing latitudes and longitudes from astronomical observations. Preuss knew nothing of such work so Frémont, characteristically impulsive and generous, worked nights to do it for him. In the spring of 1842, Frémont and Preuss went to St. Louis together, a long and fruitful relationship ahead of them. [6]

While Frémont chose hunters and teamsters and purchased his supplies, veteran trapper Kit Carson arrived in St. Louis from Santa Fe with a fur caravan. After many years beyond the Mississippi, Carson felt uncomfortable in the relatively civilized little city. Unsure of his destination but certain that he had to move on, Carson took passage on a steamer bound for the upper Missouri. On board he met Frémont, who still had not hired a guide. Carson later recalled: "I had been some time in the mountains and thought I could guide him to any point he would wish to go." Frémont signed him on, promising him the substantial monthly wage of $100. [7]

|

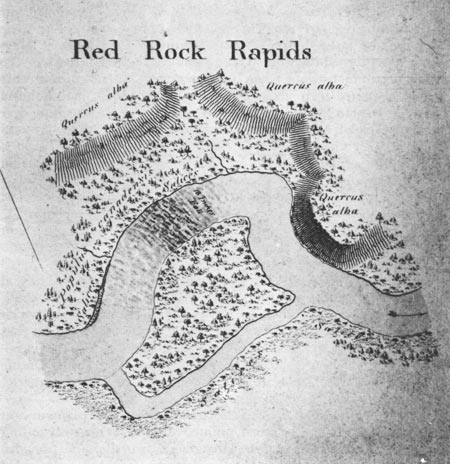

| A portion of Frémont's map of the Des Moines River, done in 1841. National Archives. |

The meeting of the young officer and the experienced mountainman marked the beginning of an important friendship. Solidly built, with clear eyes and fair skin, Carson contrasted sharply with the smaller and darker topog. They were unlike in other ways too. While Frémont tended toward flamboyance and impetuosity, Carson was taciturn and methodical. Different though they were, Frémont and Carson became fast friends and important allies. Carson was to serve Frémont well on many explorations, while Frémont, by publicizing Carson's exploits as a trapper and guide, brought fame to the obscure mountainman. [8]

Accompanied by Carson, Preuss, and the rest of the party, Frémont left the riverboat at Choteau's Landing near present-day Kansas City for the march across the plains. The routine was rigorous: "At daybreak the camp was roused, the animals turned loose to graze, and breakfast generally over between six and seven o'clock, when we resumed our march, making regularly a halt at noon for one or two hours." [9] After the noon meal, the party continued westward until just before sunset. Then the muleteers turned the wagons into a circle around the campsite, the cooks collected fuel—wood when it was available, buffalo chips at other times—and started their fires, while others pitched tents and hobbled horses. Three-man guard details served two-hour shifts, watching over the camp as their comrades slept and the horses and mules browsed quietly.

The routine of daily marches and evening camps was interrupted a short distance from Choteau's Landing when the party faced the Kansas River, high, wide, and wild with the runoff from mountain snows. The men ferried their equipment across the swollen river on a collapsible India rubber boat carried for such a contingency. When the craft overturned, scattering provisions into the river, men on shore dove into the water, "without stopping to think if they could swim," and recovered most of the supplies. A few items, including much of the party's sugar and the precious coffee which warmed the men at their morning and evening campfires, were swept downstream. Frémont bemoaned the loss, "which none but a traveler in a strange and inhospitable country can appreciate." [10] The exhausted men dried out on the far side of the river—without their steaming cups of strong, sugar-sweetened coffee. On the next day all became right again, as Frémont chanced to meet a traveler who sold him twenty or thirty pounds of coffee.

The river crossing behind them, the party moved over the plains toward the valley of the Platte. The broad, uninterrupted vistas of gently rolling hills, with the tall buffalo grass bowing gracefully in the wind, provided security for the travelers. Yet in these grasslands, a neophyte's eyes could be deceived by distant objects, and twice the expedition's routine was broken by such sightings. Nine days west of the Kansas, a man in the rear peered over his shoulder, saw movement, and sounded the alarm "Indians! Indians!" Carson wheeled his horse to the rear and rode out to assess the danger. He returned shortly to tell his nervous comrades that the intruders were six elk. Preuss too fell victim to the plains, when near the Platte he halted to sketch a rare cluster of trees. To his astonishment the grove moved, and again it was Carson who identified the disturbing vision. Preuss had seen his first herd of buffalo. By the time the party reached the forks of the Platte, near the modern city of North Platte, all were wiser and more expert plains travelers. [11]

|

| Kit Carson. National Archives. |

There the party split to meet again at the American Fur Company post of Fort Laramie. Frémont, Preuss, and four others followed the south fork into present-day Colorado to Long's Peak. After a brief meeting with a horse-hunting party led by black mountainman and one-time Crow chief James Beckwourth, Frémont and Preuss rode along the Front range of the Rockies to Laramie. Meanwhile, Carson led the main party directly up the North Platte.

While the party rested and bought supplies for the rest of the westward journey to South Pass and the Wind River range of the Rocky Mountains, Jim Bridger arrived at Frémont's camp. Already something of a mountain legend, "Old Gabe" knew as much about the northern Rockies as any man. He warned Frémont that hostile Sioux and Shoshone warriors would block the expedition's progress. Although urged by Carson and Laramie trader Joseph Bisonette to heed Bridger's words and turn back, Frémont decided to press on. Bisonette reluctantly agreed to accompany the party across the Laramie Plains to South Pass, but after six days on the trail his fears overcame him. Though all was still quiet, he turned back to Laramie, where his Indian wife and the homemade whisky known as Taos Lightning waited. The rest of the party, watched but not molested by the Indians, finished the journey to South Pass safely.

A week later, on 8 August 1842, Frémont found himself atop South Pass, the broad timberless path through the Rockies discovered in 1824 by mountainman Thomas Fitzpatrick. The gap surprised Frémont, for it had "nothing of the gorgelike character and winding ascents of the Allegheny passes in America; nothing of the Great St. Bernard and Simplon passes in Europe." [12] Instead, the grade resembled the ascent of Capitol Hill from Pennsylvania Avenue. Even Carson, despite his thorough familiarity with the country, had to search carefully to locate the pass.

Nearby began tributaries of the three great western river systems. From the eastern slope the North Platte and the Big Horn carried the melted snows into the Missouri, thence to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. On the west began the Green branch of the mighty Colorado, as well as the Snake, whose waters joined those of the Columbia on their way to the Pacific Ocean. And here, despite its undramatic appearance, was the most convenient route through the mountains, the gateway to Oregon. [13]

Descending the gentle western slope of South Pass, Frémont led his men into the Wind River range to mark the farthest point of his expedition with a dramatic flourish. On August 15, with a few companions and a specially made flag tucked inside his shirt, the topog struggled to the top of Snow Peak. With only moccasins on his feet, the thoroughly chilled but jubilant Frémont stood on the mountain's narrow snow-covered crest. There, in the stillness and solitude, he thrust a ramrod into a crevice and affixed his banner, with its star-encircled eagle clutching arrows and a peace-pipe, "to wave in the breeze where never flag waved." [14]

|

| A romanticized verston of Frémont's ascent of Snow Peak, from Republican campaign literature of the 1850's. Library of Congress. |

The return trip should have been an anticlimax, but Frémont's recklessness nearly brought disaster on the Sweetwater River. A more prudent leader would never have put the India rubber boat into the turbulent stream, but Frémont was in a hurry. On August 25, the men climbed aboard and shot three small narrows, while Charles Preuss nervously clasped his chronometer and notebook to his chest. After a halt for breakfast, the boat sped over two falls without incident, but the water and foam that spilled over a third hid a large rock. Suddenly the boat overturned, throwing men and equipment into the white water. Preuss, still holding his timepiece and journal, struggled sputtering to shore. What he saw made him miserable: "Here floated a pack, there an instrument, there a sack; here an oar, there a coat, there a shirt." Almost everything was "gone to the devil." Then his eye caught the box which contained the expedition's precious books and records. Full of new hope, he waded neck-deep in the furious stream and retrieved it—empty. Angrily, he recorded his opinion of Frémont's management: "It was certainly stupid of the young chief to be so foolhardy where the terrain was absolutely unknown." [15]

By autumn the party was homeward bound. From a scientific standpoint, Frémont's results were seriously flawed: he had failed to fix the exact position of South Pass and, in his rash attempt to shoot the Sweetwater rapids, had lost some of his botanical and geological specimens. Politically, however, the impact of his journey could hardly have been sharper.

Frémont's report was a brilliant tour de force. Under pressure from Congress for speed, he dictated the narrative to his talented wife, who added many elegant touches. By early 1843 all was ready. Published during the Senate debate on joint occupation of Oregon, the warm and enthusiastic report was snatched up by anxious readers and newspaper editors. Senator Benton's Missouri colleague, Senator Lewis F. Linn, also found immediate use for the report. From the floor of the Senate, Linn announced that the account "proves conclusively that the country for several hundred miles from the frontier of Missouri is exceedingly beautiful and fertile." This lush interior region, "alternate woodland and prairie," provided ample water for farming "in certain portions," and, most important, the valley of the Platte afforded "great facilities for emigrants to the west of the Rocky Mountains." Besides removing the label of Great American Desert from the central plains, the report gave would-be emigrants a trustworthy and detailed travel guide. After reading Frémont's account, an influential editor proclaimed: "All these foolish ideas . . . are to be dissipated—the bugbear is to disappear. . . . The nineteenth century will set upon a whole continent peopled by freemen." [16]

A second expedition, promptly agreed to by Congress, followed the successful journey to the Wind River range. In the spring of 1843, Frémont was busy organizing a party to go beyond the Rockies all the way to the Pacific. Once again he had both official and unofficial instructions. Colonel Abert directed him to follow a new route to South Pass and reconnoiter the region between the gap and the Pacific coast in Oregon. This would result in a complete survey of the interior and link Frémont's efforts with the 1841 naval reconnaissance of the coast by Commander Wilkes. Frémont's other directions came from Senator Benton, whose goals for the expedition were similar to those for the previous journey: the publicity generated would emphasize the importance of Oregon and stimulate interest in emigration and settlement. [17]

|

| The same event, shown on a postage stamp issued in 1893. Smithsonian Institution. |

Frémont set out from St. Louis in the spring of 1843, carrying some scientific equipment—a telescope, sextants, chronometers, thermometers, barometers, and compasses—but also pulling a howitzer in his train. Frémont claimed that the small artillery piece, obtained through Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny from the arsenal at St. Louis, was intended for protection against Indians. However, other exploring parties successfully passed through the hunting grounds of powerful tribes without such armament. In fact, the howitzer might be valuable in the territory of another nation, and Frémont was bound not only for Oregon but for the Mexican province of California.

Colonel Abert in Washington was furious when he heard that Frémont had obtained an artillery piece. Abert ordered the lieutenant to Washington for an explanation, but Frémont never received the summons. He was camped near Choteau's Landing when Jessie received the order at the Benton home in St. Louis. She hastily scribbled a note to her husband, telling him to leave on his exploration immediately.

As soon as an exhausted rider brought Jessie's message, Frémont hitched up his twelve-pounder, broke camp, and set out for Bent's Fort on the Arkansas. Topographer Preuss, some forty armed muleteers, mountain men, and laborers, and scout Thomas Fitzpatrick, a ruddy complected, white-haired veteran of the beaver streams who was called Broken Hand, marched with him. Frémont also had twelve two-mule carts full of gear and a light canvas-topped wagon with a good suspension to protect the instruments from the jolting cross-country trek. [18] Part way to Bent's trading establishment, Frémont sent Fitzpatrick and the wagons up the North Platte to Fort Laramie for supplies and arranged a rendezvous at Fort St. Vrain, a trading post north of modern Denver. Frémont cut south along the eastern fringe of Cheyenne country to the Arkansas and completed the journey to William and Charles Bent's outpost in mid-June.

Joined by Kit Carson at Bent's and resupplied by Fitzpatrick at St. Vrain, Frémont set out for the Great Salt Lake. On 6 September 1843, standing on a bluff above the Weber River, Frémont and Carson looked down on the lake Jim Bridger had discovered in 1824. The sight thrilled Frémont. Here was "the inland sea stretching in still and solitary grandeur far beyond the limit of our vision." Frémont followed Bear River down to the lake, and on September 7 his men penned the animals and prepared their rubber boat for a voyage on "the inland sea." That evening the explorers dined on yampa root and wild duck while a dazzling sunset that Frémont described as "golden orange and green . . . left the western sky clear and beautifully pure." [19]

The brief voyage on the lake and an equally cursory examination of the rivers that fed it from the northeast gave Frémont a favorable impression of the region, particularly of the valley of the Bear. Good grass, ample fresh water, timber, and salt all promised prosperity for cattle ranchers. The abundant bunch grass on the mountainsides, which nourished the beasts of the Indians and his own animals, could "sustain any amount of cattle and make this truly a bucolic region." [20]

Already beyond the region explored in 1842, Frémont hurried to complete his mission. Winter closed in on the north country as the party approached Fort Hall on the Snake. Determined to continue, Frémont assembled his men and offered them the opportunity to return home. Eleven left for the East, while the rest continued toward the Columbia, which they reached on October 25. They followed the river west to The Dalles, where Lewis and Clark had rested on their return from the Pacific, and established a base camp. Most of the men remained there, while Frémont and a polyglot group consisting of his black servant, Jacob Dodson, the German cartographer Preuss, a French-Creole voyageur, and three Indian guides paddled downstream in a canoe. Frémont was enraptured by the Columbia River valley, but Preuss hated it. On November 14 he recorded in his diary: "To hell with this country where it rains for five months." Frémont failed to notice his companion's bad humor. As the party floated foward Fort Vancouver, he jotted in his notebook: "A motley group, but all happy." [21]

After obtaining supplies from the generous Englishmen at Vancouver, Frémont returned to The Dalles and mustered his company for the southward journey to California. In mid-January 1844, the party faced the mighty snow-covered barrier of the Sierra Nevada range, standing tall and formidable between them and the green valley of the Sacramento River. Upon learning that Frémont planned to cross the mountains, the Indian guides gave up the enterprise as insane, leaving the party to face the knifelike wind and eye-stinging snow. For over three weeks they struggled upward, taking turns pounding the six-foot-deep snow with mallets so men and mules could continue the agonizing ascent. The mules became crazed with hunger and ate each other's tails and even saddle leather; the men in turn killed and ate the mules. February 23 was the nadir. The snow was so deep that it forced the party off the ridges onto the treacherous mountainsides, over which many of the men had to crawl to keep from falling. Frémont's feet gave way on an icy rock and he tumbled into a frigid stream. Carson leaped in after him, shared the bone-chilling bath, and pulled Frémont out.

On the following day, the exhausted and hungry band staggered over the summit. Ahead lay the green western slopes that led down to the valley of the Sacramento. Cheered by the sight, the party hurried to flee the snow-covered horror. The trial was over. After a brief and well-earned rest at Johann Sutter's New Helvetia ranch, Frémont was ready to continue his work.

During his short stay in California, Frémont accumulated a great deal of information for Senator Benton and his expansionist colleagues. In talks with Sutter and other American settlers, Frémont learned that the number of Americans trading with California ports and residing on ranches in the interior increased rapidly every year. The reasons for this growing migration were apparant. The soil was good, building materials abounded, and labor was cheap. No less clear was the hostility between the American ranchers and Mexican authorities on the coast. Many Americans talked of a revolt and independence from the weak and unstable government. It did not seem likely that Mexico could hold California for long. [22]

His inquiry completed and supplies replenished, Frémont set his course for home. He went south along the Pacific side of the Sierra Nevada, then through the montains via the San Joaquin River to the formidable Mohave Desert. The reconnaissance along the mountains disproved for Frémont the hoary myth of the Rio Buenaventura, a river thought to connect the Pacific at San Francisco to the interior. A myth was gone, but ahead lay the punishing reality of the desert. According to Frémont the party suffered "intolerable thirst while journeying over the hot yellow sands . . . where the heated air almost seems to be entirely deprived of moisture." [23]

They finally found a branch of the Virgin River, and then came across equally important aid in the person of mountainman Joseph Walker. The veteran trapper guided the party the rest of the way around the southern edge of the Great Basin to the Sevier River and Utah Lake, just south of the Great Salt Lake. Frémont had circled—and named—the Great Basin after an eight-month journey of 3,500 miles.

While camped on Utah Lake, Frémont arrived at an understanding of the nature of the Great Basin. He perceived the region as a vast interior drainage system and returned home with the first comprehensive notion of its basic characteristics. The identification of the basin and the concomitant destruction of the myth of Buenaventura were among Frémont's greatest achievements as an explorer. [24]

His second report, as polished and informative as the first and even more exciting, had many avid readers. Large printings, public and private, gave the book wide circulation, and privately published guidebooks, such as Joseph E. Ware's The Emigrant Guide to California, drew heavily on Frémont's narrative. Abroad as well as at home, Frémont's report was warmly received. In London, the Royal Geographical Society heard Lord Chichester summarize the work. In Potsdam, the Prussian sage Alexander von Humboldt commended the author's "talent, courage, industry, and enterprise." At Nauvoo, Illinois, Brigham Young, swayed by Frémont's description, chose the area around the Great Salt Lake as the region his people would settle. And many a pioneer family, like that of Josiah and Sarah Royce, made its way to California "guided only by the light of Frémont's Travels." Writing to her absent husband in 1846, Jessie Frémont noted, "As for your Report, its popularity astonished even me, your most confirmed and oldest worshipper." [25]

|

| An emigrant wagon headed for the Great Salt Lake. Library of Congress. |

Frémont's sensational report included an excellent topographical map by Charles Preuss, The large sheet, which depicted the routes of both of Frémont's expeditions, was a cartographic milestone. By accurately representing the basic features of the new country, Preuss changed the course of western mapmaking. No longer would cartography be based on myth and speculation. [26]

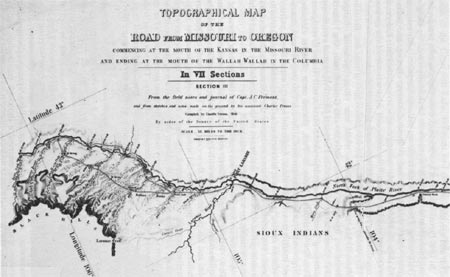

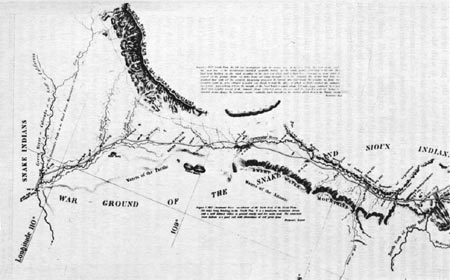

In 1846 Preuss completed another map, more important for prospective emigrants than the first. On seven sheets he carefully traced the Oregon Trail, using Frémont's narrative to indicate campsites with essential grass, wood, and water and to show distances, climate, and Indian inhabitants. Widely popular among those who took the Platte River road to Oregon and California, this annotated atlas was one of the greatest contributions Frémont and Preuss made to the development of the West. [27]

Rewarded with a double brevet promotion to captain, Frémont planned his next expedition while war clouds gathered. Danger threatened from two quarters, Mexico and Great Britain. On 1 March 1845, shortly before he left office, President John Tyler signed a resolution annexing Texas, whose independence Mexico still refused to recognize. The new president, James K. Polk, elected on a platform claiming Oregon, also harbored designs on California. Vast empires were at stake and conflict seemed inevitable. Again the agent of expansionist politics, Frémont carried two sets of instructions as he assembled his party in St. Louis. His written orders were to survey the Arkansas and Red rivers, remain east of the Rockies, and return to the States before the end of the year. Actually, he was California-bound. [28]

A miniature Army—some sixty men in all, including artist Edward M. Kern, scout Joseph Walker, and many hardy veterans of past explorations—left St. Louis with Frémont. A dispatch to Carson brought him and his partner from their ranch near Taos. A band of Delaware Indians joined up, and so did some roving trappers. Soon the ranks swelled to nearly one hundred. Also with him were two inexperienced topogs, Lieutenant James W. Abert, the colonel's son, and Lieutenant William G. Peck. They and thirty men left the main party at Bent's Fort to reconnoiter the Kiowa and Commanche country. The rest went with Frémont: "A well-appointed compact party of sixty," he described them, "mostly experienced and self-reliant men, equal to any emergency likely to occur and willing to meet it." [29]

|

| Section III of the Preuss atlas, showing the location of Fort Laramie. National Archives. |

|

| Section IV of the Preuss atlas, showing the location of South Pass. National Archives. |

Late October found Frémont on the southern shore of the Great Salt in Mexican territory, ready to push across on the barren rugged expanse of the Great Basin. The view to the west was "nothing but mountains," serrated ridges running north and south. Looking out across their crests seemed to Frémont "like looking lengthwise along the teeth of a saw." Names he wrote upon the map—Pilot Peak, Humboldt River, and Walker Lake—marked his route through the desert, from watering place to watering place and from pass to pass. The region, with its stony, black mountains sagebrush-covered floor, boiling springs, disappearing streams, and alkaline lakes deserved a thorough exploration, but, as Frémont afterward explained "the time needed for it would interfere with other objects, and winter was at hand." [30] At the foot of the Sierra Nevada in late November he divided his party, sending the main body under Kern south to Walker's Pass and thence to the San Joaquin valley, while, with Carson and the Delawares, he struck over the mountains to Sutter's ranch. Reunited in California the following year, the party turned from exploration to conquest. With the United States at war with Mexico, the expedition formed the spearhead of the Bear Flag Revolt. As the nucleus of the California Battalion, a rag-tag, collection of frontiersmen and adventurers, Frémont and his men helped overthrow Mexican rule and hold the province until it could be occupied by the Army.

Frémont's career as a topographical engineer ended with his involvement in the conquest of Mexico. [31] While not deserving the title of pathfinder—that properly belonged to the frontiersmen who guided him through the river valleys and mountain passes—he marked the important trails on maps and in the minds of his countrymen. [32] His reports assaulted the notion of a Great American Desert, and dramatized the possibilities of Oregon, California, and the valley of the Great Salt Lake. An able agent of Senator Benton's expansionist politics, he provided accurate information on the vast new country for those bent on westering. When the American eagle was ready to make its screaming way to the shores of the Pacific, it followed the routes marked by Frémont.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

schubert/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 17-Mar-2005