|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers |

|

PROMOTING SOUTHERN CULTURAL HERITAGE

LINDA CALDWELL

ETOWAH ARTS COUNCIL

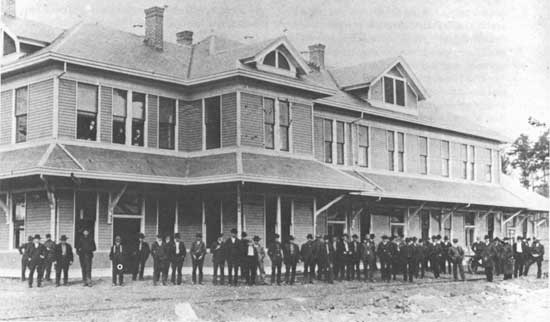

"It was a young town. Filled with young people. All with money in their pockets." That's the way Mrs. John Palmer, daughter of a Louisville and Nashville Railroad blacksmith, remembered Etowah, Tennessee in the early part of the twentieth century. Mrs. Palmer was one of thousands of people who moved to the new railroad town between 1906 and 1920. She recalled that the townspeople were interested in building homes, schools, and churches. Copper miners who lived in nearby Ducktown and Copperhill had money in their pockets too; They lived in mail-order houses that were furnished by the copper company, but they were also interested in building churches and schools.

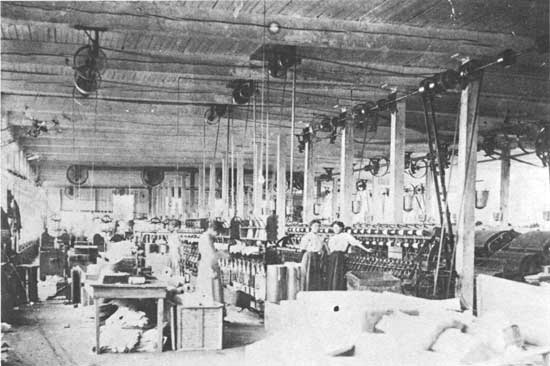

It was a unique time in the mountains of southeast Tennessee, marked by dramatic changes in the lifestyles of people who moved from farms to rubber stamp towns. Sons of Monroe County farmers went to work for Babcock Lumber Company near Tellico Plains. Tie hackers and teamsters hauled wooden ties for new railroads that laced the towns together and brought the world to their doorsteps. Gold was mined and panned at Coker Creek. Daughters moved to Englewood and Delano to work in textile mills and join in the industrialization of the southern Appalachians.

That era will provide the theme for a cultural tourism program that is one of sixteen pilot projects for the National Trust for Historic Preservation Tourism Initiative a three-year program designed to assist communities develop tourism plans that focus on historic and cultural resources.

|

| View of women employees at the Eureka Cotton Mills in Englewood, Tennessee ca. 1916. Photo courtesy of the Community Action Group of Englewood. |

Selected as one of four Tennessee and one of sixteen national pilot areas, the counties of McMinn, Monroe, and Polk are working on a plan that will include a driving tour/exhibit that will trace the industrialization of the region once known as the Cherokee Overhill [territory]. The boundaries of the pilot area closely resemble the boundaries of the Cherokee Overhill, and that explains the title chosen for the project, "The Tennessee Overhill Experience: From Furs To Factories."

Cherokee history is an important part of the story. The fur and hide trade that sprang up between the Cherokee and the European traders represented the introduction of the Tennessee Overhill to the world market. Existing exhibits at Fort Loudoun and Sequoyah Birthplace Museum near Vonore Tennessee discuss the first chapter of the story.

Other exhibits, such as "Growing Up With The L&N: Life And Times In A Railroad Town", located in the L&N Depot in Etowah and the various exhibits and buildings that comprise the Ducktown Basin Museum allow visitors to examine regional railroading and mining history.

The town of Englewood is working with the Tennessee Humanities Council to develop an exhibit and book that will focus on working-class women in the Englewood textile mills and how Englewood, Tennessee fits within the story of what was occurring across the South. The Tennessee Humanities Council is not unfamiliar with the pilot communities in the Tennessee Overhill. In fact, it was the Etowah Museum project, which was funded in large part by the Council, that spawned the southeast Tennessee Cultural Tourism Plan.

There is no museum at Coker Creek, but the local Ruritan Club recently published a book on the history of the Coker Creek Gold District. Realizing that gold was an important but not exclusive source of income, the book supplies historical information on the cottage weaving industry, logging operations, and whiskey making that were once an important part of the Coker Creek economy.

|

| View of the Burra Burra Mine in 1940. This is not the site of the Ducktown Basin Museum, operated by the Tennessee Historical Commission. Photo courtesy of the Ducktown Basin Museum. |

The Tennessee Overhill is a diverse geographic region. Mountains rise from the banks of the Hiwassee, Tellico, Little Tennessee and Ocoee Rivers. The Ocoee is well known for its white water sports and as a possible site for the 1996 Olympics. But the Ocoee story is far more complex than kayaks and slalom races. Historic power houses sit on its banks, and a wooden flume line built in 1912 snakes along the rock face that rises from the river. Now owned by the Tennessee Valley Authority, the power houses, dams, and flume line are reminders of the massive undertaking that allowed electricity to come to rural southeast Tennessee. Both TVA and the Cherokee National Forest plan to use signs to interpret parts of the Ocoee history, such as the building of the Copper Road and the little community of Caney Creek. Built to house Ocoee Flume Line workers, Caney Creek was accessible only by a swinging bridge and boasted tennis courts and an electric trolley.

Tucked in a gap on the Hiwassee River is the Historic District of Reliance. Nestled against the Cherokee National Forest, Reliance, with its turn-of-the-century buildings and general store, offers a glimpse of what life in a farming community was like at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Elisha Johnson Mansion, home of the Iron Master for the Cherokee Iron Foundry, sits on the Tellico River. After the removal of the Cherokee, the foundry was operated by white settlers until its destruction during the Civil War. Although the foundry is gone, the mansion remains and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A short way downniver is the town of Tellico Plains, a town that has worn a variety of identities. Babcock Lumber Company built houses on what is now called Babcock Street. Stokely Foods built a cannery there and raised vegetables on the Plains where the Cherokee city, Great Telaquah, once sat. During World War II, German POWs were housed on the Plains and worked in the cannery. By the time the Cherahala Skyway between Robbinsville, North Carolina and Tellico Plains opens, it's possible that Tellico Plains could assume another identity. A recent development that involves installing Alpine facades on turn-of-the-century buildings is underway on the little town square. One wonders if, in a hundred years or so, such developments will be considered artifacts of a period when small mountain communities took on new identities practically overnight in an attempt to survive economically.

Drastic change is not so welcome in the Copper Basin. Teachers and students at Copperbasin High School are exploring how the physical landscape affects the landscape of the human soul. Many years ago, the hills in the Copper Basin were denuded by open ore smelting, timbering, and erosion. For some time an aggressive reforestation program has been underway. Although the old-time residents of the Basin understand the need to return trees to the land, they are sad about the disappearance of a landscape that was home to them. The Ducktown Basin Museum hopes to acquire a parcel of land with barren red hills that adjoins the museum to preserve forever. The Town of Copperhill is working to unearth an unusual element of its unique landscape—steps built prior to automobiles for townspeople to use to climb the steep hills where the company houses perched above the little town.

The driving tour/exhibit is only one of several projects underway as part of the Tennessee Overhill Experience. Other plans include development of special events, a heritage events calendar, a cultural conservation forum, and a self-guided photography tour.

Last November a rail excursion ran for two days between Etowah and Copperhill. One thousand excited passengers rode on vintage trains across the historic 1898 Bald Mountain Loop and joined local volunteers in celebrating the railroad and mining heritage of the Tennessee Overhill. The rail trips are an excellent example of the kinds of partnerships that the National Trust is encouraging in each of its sixteen pilot areas. CSX Transportation provided operational support while four labor unions donated services as engineers, trainmen, conductors, and car hosts.

The photography tour has produced an interesting side effect. Photography students at a local high school recently complained that there is nothing in their town to take pictures of. Imagine their surprise when they discovered that amateur and professional photographers will be invited to their town to do just that.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development have worked closely with the Overhill project to develop a Community Education Plan. People are more or less aware of the value of the natural resources and grand historic structures found in the Tennessee Overhill. Not so readily accepted is the notion that mill ruins, company houses, and historic transportation routes are also valuable.

Another challenge for the Tennessee Overhill Community Education Program is the prevailing "either-or" attitude about tourism. Some people want development at any cost. Others fear that any development will create havoc. If tourism plans are made without regard for residents and inappropriate development is encouraged, then tourism will become just another extractive industry. Conversely, if towns are unable to maintain services essential for a desirable quality of life or offer business opportunities, future generations, also a valuable resource, will be drained away.

A happy medium is, of course, the preferred solution. However, the Tennessee Overhill Advisory Committee is aware of the fragility of such a balance. Educating residents to the need for protection of the uniqueness of the Tennessee Overhill is an important objective of the local plan.

The primary goal of the Tennessee Overhill Experience is to develop a tourism product that will increase visitation to the region, serve as an educational tool, and act as a catalyst for economic development. In order to achieve this goal, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development are providing training and technical assistance for planning, museum development, interpretive planning, regional tourism development, community education, marketing, fund raising, and public relations.

The southeast Tennessee project has pledged to follow the principles of heritage tourism set forth by the National Trust for Historic Preservation:

* AUTHENTICITY AND QUALITY - Tell the true stories of the Tennessee Overhill.

* EDUCATION AND INTERPRETATION - Names and dates don't bring a place or event alive, but the human drama of history does.

* PRESERVATION AND PROTECTION - A community that wants to attract tourists must safeguard its future by establishing measures to protect the very elements that attract visitors.

* LOCAL PRIORIES AND CAPACITY - Ensure that tourism is of economic and social benefit to the community and its heritage.

* PARTNERSHIP - Cooperation among business leaders, operators of historic sites, local governments, and others is important to the preservation and tourism communities.

Everyone involved with the Tennessee Overhill Experience is aware that this project is no more than a part of the most recent chapter in the story of the industrialization of the Tennessee Overhill. They believe that their challenge will be to make this chapter one of which they can be proud.

|

| 1907 view of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad Passenger Station in Etowah, Tennessee. It was the first structure built by the railroad company in the planned community. Photo courtesy of the Etowah Museum. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

appalachian/sec17.htm

Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008