|

SALINAS

"In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions |

|

CHAPTER 4:

ABO: THE CONSTRUCTION OF SAN GREGORIO (continued)

THE THIRD CONVENTO AND LATER CHANGES (continued)

The Third Reconstruction of the Convento

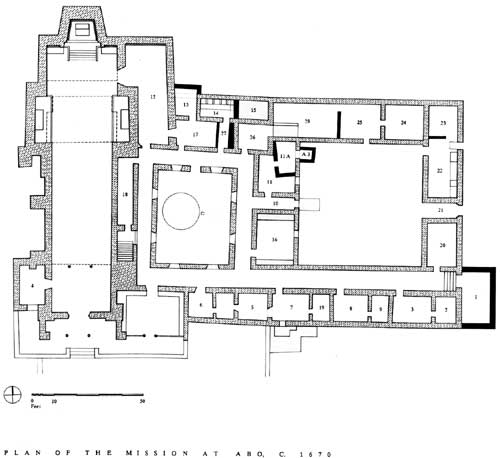

Soon after his arrival in 1659, Fray Antonio Aguado decided that the convento needed a little modernization. He began the alteration of rooms 13, 14, and 15 along the north side of the convento to make space for a latrine for the friars. [55]

The alterations had the general intent of separating the latrine from the other surrounding rooms, while communicating with the ambulatorio. The design removed the stone wall between rooms 14 and 15, and replaced it with an adobe wall about two feet farther east. The construction crew cut new doorways through the wall between rooms 14 and 17 and the wall between the ambulatorio and room 17 (two of the walls surviving from the first convento plan), and removed the wall between rooms 17 and 26. They then built in two adobe walls to create room 27, a short corridor from the ambulatorio to the latrine. The construction may have added a window through the north wall of the convento, if one had not been here before. Ventilation is important in a privy.

The design of the latrine strongly resembles the lower portions of latrines used at missions in Mexico in the sixteenth century. [56] Each of the five square openings was probably covered by a wooden cover and seat, and thin stone partition walls on the crossbeams divided the privy into five stalls. Measurements indicate that the southern wall may have been a lower step, with the seats about twenty inches higher. There was probably some method for periodically cleaning out the pit. It is possible that a stone-lined drain ran to and from the pit, to channel a stream of water for periodic clean-out. Such a setup seems to have been built at Mission San José in San Antonio, Texas, and a suspicious-looking arrangement of slab-lined channel and small rooms or cubicles suggests a latrine set-up at Pecos.

The latrine was called a "turkey pen" by Toulouse, based on the presence of eggshells, the fragments of shallow pottery "watering pans," and what he considered to be "bird droppings." [57] Toulouse indicates that the materials from the pit of the latrine had been analyzed by Volney H. Jones and the "droppings" positively identified as bird dung. However, in Appendix 2 of Toulouse's report, Volney Jones states that the "material from the turkey corrals consisted of lumps of light grey more or less porous material chiefly of organic origin. There seems to be little question that it was primarily turkey dung." This is hardly a positive identification. In fact it sounds like circular reasoning: Toulouse told Jones that the material was from a probable turkey pen, so Jones stated that the material was probably turkey dung, thereby proving to Toulouse that the pit was a turkey pen. There seems to have been no definitive test applied to the dung that proved it to have been the product of turkeys or any other bird. Field experience has shown that turkey dung tends to be a distinctive yellow-gray, while that of omnivorous mammals, including human beings, is usually a friable gray material in archeological contexts.

Materials found in the pit are typical of those found in any privy pit, and the appearance of the dung is consistent with what would be expected in a privy. The author therefore suggests that the "turkey pens" of Abó were in reality what they appear to be: the latrine for the friars of the convento. Similar privies are lacking at the other conventos in the Salinas area, and in fact at virtually every other mission on the Northern Frontier. This seems to be predominantly the result of chance. For example, privies are mentioned in the inventories of three eighteenth-century missions in San Antonio, Texas. One of the privy rooms was later converted to the kitchen of the rectory of the church, and is not available for excavation. No excavations have been conducted in the likely location of the second, and insufficient investigations at the third. A privy is mentioned in the convento at Acoma by Dominguez in 1776, but no investigations have been made here, either. Similar circumstances of a failure to recognize these simple structures or too limited investigation probably explain their lack in most cases. At Quarai, however, another alternative is suggested by the evidence. Here, the trusty chamberpot seems to have been the preferred method of handling this common necessity: see, for example, the largely complete chamberpot found in the debris filling the patio kiva and now on display in the small museum at the visitor's center. It is not identified to visitors as a chamberpot. [58]

The Construction of 1667 to 1672

Late in the life of the convento, the Franciscans partitioned off a portion of the storeroom (room 11a), and at the same time built a small, massively-walled room next to the kitchen storeroom and extending into the second courtyard on the east (room A-3). This room probably communicated with the kitchen storeroom by way of a converted window. It could have been two stories high, with a stairway up through the converted window to the second story of A-3. Unfortunately, too little of the wall survived to confirm this, and insufficient archeology has been carried out in the area to determine if the traces of a wooden stairway might remain.

At the same time, the missionaries probably built room 1 at the end of the residence hallway. [59] Room 1 appears to have been built with its floor at ground level, and with a stairway up from the end of the hall to its roof level. It was apparently entered by a hatchway through the ceiling of the first floor. This sort of secure room was also built at the other two missions. The rooms usually had a second story and a hatchway entrance to the lower floor, and were usually built near the kitchen. They were probably constructed during the severe famine of 1667 to 1672, when food supplies were being shipped from missions with surplus food to the southern missions. The rooms seem to have been used to protect critical food and seed supplies from theft by the Pueblo Indians and raids by the Apache.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

sapu/hsr/hsr4g.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006