|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

V: THE GREAT DEPRESSION (continued)

The First New Deal

The economic crisis sparked by the stock market crash of late 1929 only deepened during the early 1930s. Before Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in early March 1933, a total of 5,504 banks had closed. Nearly all the remaining banks had been placed under restriction by state proclamations. That month, President Roosevelt took immediate steps to strengthen the banking system while initiating his nationally radio-broadcasted "fireside chats" in an attempt to calm the fears of the nation. Congress then held a 100-day session to address unemployment and farm relief. The resulting legislation was aimed primarily at relief and recovery. Known as the "First New Deal," it lasted roughly from 1933 to 1935.

By an act of March 31, 1933, the agency known as Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) was created to provide work for the unemployed. The law authorized the federal government to provide work for 250,000 jobless male citizens between the ages of 18 and 25. Their duties were to be reforestation, road construction, prevention of soil erosion, and national park and flood control projects. Roosevelt's Executive Order 6101 of April 5, 1933, authorized the commencement of the program. Robert Fechner was named director of the ECW, later more commonly referred to as the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. [833] He served in that position from fiscal years 1933 through 1939. Four government departments (War, Interior, Agriculture, and Labor) cooperated in carrying out the program. At its peak the CCC had as many as 500,000 on its rolls; over two million were enrolled over the course of the program by the end of 1941. [834]

Placed under the direction of Army officers, CCC work camps were established with youths receiving $30 per month, $25 of which went to their families. The government provided room, board, clothing, and tools. The enrollee was expected to work a 40-hour week and adhere to camp rules. Initially, enrollment for conservation work was limited to single men between the ages of 18 and 25. New categories were opened during the months of April and May 1933. On April 14 enrollment was opened to American Indians, who were generally allowed to go to their work projects on a daily basis and return home at night. On April 22 enrollment was opened to locally employed men (known as LEMs). The marriage and age stipulations did not apply to these men, most of whom were in their 30s or 40s. While a limited number of skilled local men were employed, the bulk of the CCC work force came from the unemployed in large urban areas. On May 11 enrollment was opened to men in their 30s and 40s who were veterans of World War I. These enrollees were given special camps, operated with more leniency than the regular camps, and selection was determined by the Veterans Administration rather than the Labor Department. [835] Except for a few installations in Northern states, the camps were racially segregated into white, Negro, and Indian camps.

The program was to be started in the East and extended to the rest of the country as soon as possible. Roosevelt's goal was to have 250,000 youths at work in national parks and forests by July 1, 1933. Various agencies of the Department of the Interior directed the work of the CCC camps: the Office of Indian Affairs, the Bureau of Reclamation, the General Land Office, the Grazing Service (also referred to as the Division of Grazing), the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. In the state of Arizona, the National Park Service directed camps in Grand Canyon National Park and the following national monuments: Petrified Forest (NP-8), Chiricahua (NP-9), Saguaro (NP-10), and Wupatki (NP-11). In addition, Mt. Elden Camp (NP-12), located at Walnut Canyon, performed work there, at Wupatki, and at Sunset Crater National Monuments. [836] In the case of Pipe Spring National Monument, however, the Grazing Service oversaw the camp. Designated Camp DG-44, its work activities concentrated on the public domain. [837] By contrast, for its first two years CCC camps administered under the Park Service were forbidden from working outside park boundaries.

On March 16, 1933, the NPS Washington office issued a memorandum to parks and monuments requesting a report of the number of unemployed in the area, projects on which they could be put to work, and available housing. Heaton reported that 25 men were unemployed in the area of the monument, 18 were supporters of families, and seven were single. All came under the class of common laborer. Unemployed Indians, he reported, were not included in this count as the local Indian Agency was caring them for. Heaton stated that he could house 40 or more men at the monument. (Presumably he was considering the fort and two cabins for housing.) No plans had been formally prepared for the monument, but Heaton suggested a number of possible work projects. [838]

The Office of Indian Affairs participated in the CCC program, and more than 88,000 Indian men enrolled nation wide. The work performed under this program was generally carried out on Indian reservations. CCC regulations were changed according to the realities of reservation life. The War Department was not involved in camp administration on reservations. [839] In September 1933 Heaton reported to Southwestern National Monuments Superintendent Frank Pinkley, "Nine of our Indians have got work in one of the CCC camps for the winter and a large percent of our unemployed are in these camps. There are five of them within 150 [miles] of here." [840] It would be two more years, however, before a CCC camp would be located at Pipe Spring National Monument.

Of earlier importance than the CCC at Pipe Spring National Monument was the Civil Works Administration (CWA), established on November 8, 1933, as an emergency unemployment relief program for the purpose of putting four million jobless persons to work on federal, state, and local make-work projects. Funds were allocated from Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA) and Public Works Administration (PWA) appropriations supplemented by local governments. [841] The CWA was created in part to cushion the economic distress over the winter of 1933-1934. It was terminated in March 1934 and its functions transferred to FERA.

On the date of the CWA's establishment, Director Arno B. Cammerer issued Circular No. 1, "The Civil Works Program," which was distributed to parks and monuments. Data was requested from the parks and monuments to enable the Washington office to compile a comprehensive outline of possible Civil Works Projects with an estimate of the number of men who could be employed. On November 8, 1933, Chief Engineer F. A. Kittredge telegramed Heaton to inquire how many men and women he had working on Civil Works Projects. Heaton telegramed back that he had not yet been authorized to commence work, that he would only be employing men, and that men were available and ready for work. On November 15 Kittredge informed Leonard Heaton that his office had wired Washington, D.C., requesting 15 men for work at Pipe Spring National Monument, at a cost of $3,510 for the three-month program. The men were to live at home while working. The projects listed for the men to work on were described as "repairs to one-fourth mile road, general clean-up, shifting outhouses, etc.; repairing and rebuilding fences, grading, and planting." [842]

On December 3, 1933, Southwestern Monuments headquarters notified Heaton that funding for work at Pipe Spring had been approved by the Washington office under the Civil Works Program. The monument was allotted $3,167 for labor and $405 for other expenditures. Workers authorized included 13 unskilled men, 1 semi-skilled man, 1 skilled man, and 1 foreman. The next day, Heaton wrote to Pinkley about his plans to use the men:

I have spent some time in planning what work that would be the most benefit at present. I have come to the conclusion that the road be the first consideration, which will be connected up with the changing of the wash so that it will run the water down the east side of the campgrounds and through the place where the old stock corrals were, the filling up of the present wash preparatory for the building the restrooms and residence buildings as Mr. Langley has them planned.

The rebuilding of some of the rock walls and lay[ing] them up with mud [mortar] to keep the rats and rodents from digging out the soil and thus causing the [fort] walls to fall down, also the rock walls around the ponds be pointed up with some material to keep out rodents.

Then I would like to fix up the tunnel [spring] some way and level up the meadow. Then there is the fencing of the monument and putting in a good cattle guard on the east. [843]

Heaton estimated that three or four teams of horses would be needed to keep the men at work on the projects and that they could be accomplished in the 12-week period allowed.

On December 14, 1933, Heaton received the go-ahead from Pinkley to put the men to work. He went to Short Creek to request 16 men from the local Civil Works Administrator. Clifford K. Heaton was hired as foreman at $30 per week. Unskilled men on the work teams were paid 30 cents per hour. The men were to work five days a week, six hours per day. [844] Leonard Heaton purchased materials in Kanab the next day. Park Engineer Arthur E. Cowell arrived from Zion National Park on December 16, as did eight workmen. Cowell, Heaton, and two of the men surveyed the road from the west to east boundary in preparation for its relocation. Five more men arrived two days later, joined by another three on December 23. Heaton had the men work on the monument road and on cleaning up the meadow and the tunnel. The men were to relocate the road that passed between the ponds and the fort to a location just south of the ponds. An archeological discovery of old watering troughs was made during the first week of roadwork, as Heaton describes below:

We had a surprise in digging out the road where we are taking a part of the hill off. After we had taken off about eight inches of dirt from the highest part we began to find cedar and pine logs which had hardly decayed at all. When we reached the 18-inch level we dug up about 20 feet of 2-inch pipe, 15 feet of 1- inch pipe, and some scrap iron. There were several different colors of dirt, indicating that it had been hauled in at different times and from different places. After talking with some of the old timers about my finds, I found that at one time the troughs for watering stock were about in that place and the timbers had been put there to keep the ground from getting soft and sloppy. I am taking this hill down about 24 inches and putting the dirt in the low place east of the pools. [845]

In addition to the roadwork, Superintendent Pinkley directed Heaton to have the entrance to tunnel spring cleaned out, to put in "some sort of rock box for the water," to install cattle guards, and to rebuild monument boundary fences. At the end of a busy December, Pinkley lauded Heaton in the Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report for his careful attention to the "pages and pages of instructions" that were sent out related to reporting requirements for the Civil Works Projects. Headquarters reported that Heaton "turned in the best papers that have come out of the field." [846]

Meanwhile, the Park Service's Branch of Plans and Design in San Francisco completed the monument's first "General Development Plan." [847] Chief Engineer Kittredge forwarded the plan to Cowell at Zion National Park at the end of December 1933 with the request that he proceed to Pipe Spring as soon as possible to stake out the various developments. The plans called for the construction of a campground and comfort station, to be located east of the fort ponds and north of the monument road; a parking area south of the fort ponds and monument road; and two residences, an equipment shed and garage, just below the parking area. [848] All development was sited in close proximity to the fort. Director Cammerer approved these plans in February 1934.

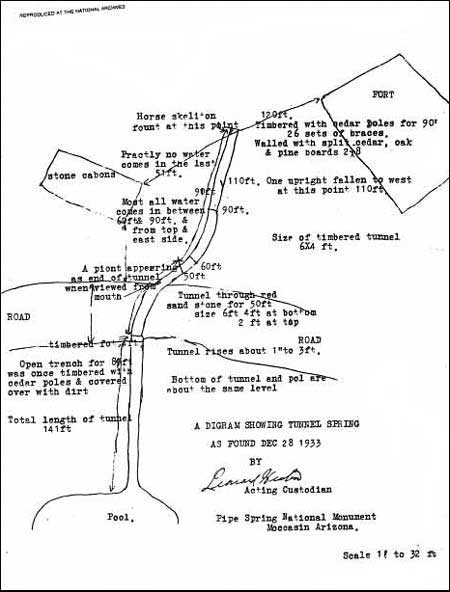

As Heaton and the workers cleaned out the tunnel, they discovered that the original bottom was 2.5 feet lower than previously thought. Heaton speculated, "If we rock up the sides of the tunnel as we had planned, it will mean that the upper meadow pool will be lowered about two feet. I will therefore wait until some Landscape man comes in before I rock it up." [849] On January 5, 1934, Heaton reported on the progress made cleaning out the tunnel. With the help of some boy scouts, he took measurements to send to Pinkley. The first part of the tunnel was six feet high and four feet wide. The tunnel went 88 feet (including four feet of timber at the mouth of the tunnel) until it reached "the hill." At that point, tunneling through sandstone, it proceeded another 50 feet. Within the rock, its dimensions were four feet wide at the top and two feet wide at the bottom. Heaton made several surprising discoveries as he explored the tunnel. The first was that most of the water was encountered between 60 and 90 feet into the tunnel, and practically none at the terminus. The other surprise was at the end of the tunnel a horse's skeleton was found. Heaton stated the horse once belonged to O. F. Colvin who lived at Pipe Spring "from about 1908 to 1914." "He never knew what became of his horse," reported Heaton. [850] Heaton included a rough sketch map with his letter (see figure 66).

66. Sketch map of tunnel spring, December 1933

(Drawn by Leonard Heaton, courtesy National Archives, Record Group

79).

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window - ~92K)

Cleaning out the tunnel had created a new problem however. Heaton wrote,

Now the trouble I am having is to decide as to what to do with the tunnel, for the bottom is about on the level of the bottom of the upper pool, and if the flow of the water is changed much by cleaning it up we may have to do away with the pool. The sides keep sloughing in so that we will have to cut the banks on a slope about 20 percent to keep them from caving in.

Mr. Cowell suggested that we place a 3 or 4-inch pipe in at the mouth of the tunnel, then cover up the open trench out to the pool, but I am in favor of rocking it up if possible, as it would add to the beauty of the place. [851]

Chief Engineer Kittredge approved of Cowell's plan to pipe water out of tunnel spring. He wrote, "I see no reason why you should not construct within the tunnel the desired catch basin at each spring, and conduct the assembled flow of water from them to outside the tunnel." [852] Kittredge advised Cowell to construct the collection boxes "in a very permanent manner, preferably out of concrete." Kittredge assured Cowell that the meadow pond would not be lost if he kept the pipe at the same elevation water had flowed through the tunnel in the past. Ultimately, 75 feet of two-inch pipe was placed in the tunnel to carry water to the upper meadow pond. The mouth of the tunnel and pipeline were covered up and a man-hole was left for inspection and cleaning purposes. [853]

Civil works projects continued into early 1934. Harry Langley made several trips to Pipe Spring during this period, one on January 31 and the other on February 6. He reported to Chief Architect Thomas C. Vint that the CWA crew had been cleaning out tunnel spring, grading the campground area, constructing a road through the monument on a new location, planting the campground area, and constructing a diversion ditch to protect the campground from flooding. [854] Langley recommended that the Heatons' store be removed at once to allow completion of the parking area grading (it was situated right in the center of the proposed parking area). He also opined, "The condition of the fort will always be a disgrace to the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations until such time as all living quarters are excluded from it." [855] Vint forwarded Langley's report to Director Cammerer, emphasizing the importance of providing the custodian with a residence. Cammerer replied that Langley's recommendation for development "seems to be to be just about what is desired for Pipe Spring National Monument." [856] Descriptions and estimated costs of the proposed projects, Cammerer wrote, would need to be included by Pinkley when he sent in his request for future Public Works Administration projects.

At Superintendent Pinkley's request, Heaton developed a list of additional projects to undertake if CWA work continued. Proposed projects included work on the east and west approach roads; construction of a water system for the campground and residences; irrigation of trees and meadow; planting of lawns and trees; quarrying of stone for the proposed comfort station, residence, and garage; and completion of filling the wash. Heaton recommended that the irrigation project be done as soon as possible for, once the water was divided three ways, he asserted, "there will be not enough water to irrigate the meadow and trees by the ditch method and to plant trees and lawns as being planned." [857] He also suggested that a trail be constructed "to the top of the hill beginning at the fort going west along the old road where the rock was hauled in for the fort then on top at the monument boundary, from where a good view of the surrounding country and mountains [can be seen] and then coming back down the hill east where the cactus and other plant life can be seen." [858] (Heaton's idea for a nature trail would be around for many decades before it was implemented.) The irrigation system was "first and most important," wrote Heaton. Vegetation was then being irrigated by the ditch and flood system and Heaton felt the Park Service should convert to a piped system and use of sprinklers. A water system would be required if the new residences and comfort station were to be built as planned. Only a few of these projects would ultimately be constructed during the 1930s.

On February 15, 1934, the 30-hour-work week for CWA crews was cut to 15 hours and Heaton was required to lay off some men. Work continued on irrigation ditches and more trees were planted. Cedar and pine trees were set out on the south side of the monument on land that had been farmed. On March 15 Heaton reported to Pinkley that construction on the road and cattle guards was still incomplete. Langley returned to Pipe Spring on March 16 to inspect work projects, to discuss landscaping plans for the monument with Heaton, and to do some fishing in the fort ponds. After six hours of work, Langley spent one hour fishing. Heaton reported he caught five good-sized trout and that Langley asked him to "get some more fish so that he can get to fish every time he comes in." [859] (Heaton made numerous efforts to obtain more fish over the next few years to no avail.) In addition to visits by Langley, Park Engineer Cowell visited Pipe Spring about every other week to oversee CWA work while it was ongoing.

The work program was terminated at the monument on March 22, 1934, leaving Heaton to finish up projects as best he could. Heaton reported that due to the early layoffs, "I was not able to complete a single project." He asked to retain surplus materials associated with the CWA work so that he could complete the projects. The leftover cement was needed to make headwalls for culverts and a rock wall to divert flood waters around the campgrounds. ("If this wall is not completed the first flood that comes will undo all the filling in for the new road, also damage the campground considerable," Heaton explained. [860] ) Wire and staples were also needed to complete the boundary fence to keep out cattle and horses (there was about 250 yards still to be fenced). The surplus galvanized pipe was needed to irrigate trees on the south side of the monument; gates were needed on the monument road to keep loose stock from entering the monument area.

In April Heaton sent in a final report on the projects completed under the CWA program from December 16, 1933, to March 22, 1934. The projects included relocation of the monument road, flood diversion in the area of the new campground, removal of old fences, trimming of deadwood from trees, work on tunnel spring, removal of old reservoir dikes and grading the campground area, survey of boundary lines and installation of new fencing (cedar posts and barbed wire), and preparation of a contour map of the monument by Zion National Park engineers. The work to construct an irrigation system to water monument vegetation had been started but not completed. Heaton reported a number of archeological finds were made during the relocation of the road and grading of the campground, all historic period materials. He estimated that the projects were 80 percent complete by the time work was stopped. The weather had been "ideal," Heaton stated. No work days were lost due to bad weather.

Park Engineer Cowell also filed a formal report on Civil Works Projects at Pipe Spring. (The Pipe Spring work was designated CWA Work Project F68, U.S. No. 8.) In addition to the projects listed by Heaton, Cowell's report noted that boundary survey markers had been placed and location surveys made of the road, campground parking loop, and other planned developments. Topographic surveys were completed for the entire area. Only 80 percent of the grading for the relocated road had been completed; parking area grading was only 40 percent completed. Culvert pipes for drainage had been installed but headwalls still needed to be constructed. Cattle guards had been sited at the monument's east and west boundaries, but not constructed. Boundary fences were about 75 percent completed. Flood drainage rockwork was "about 20 percent" complete. In describing work on tunnel spring, Cowell stated that the outer four feet of tunnel (which was timber) and 14 feet of the tunnel were cleaned out and stoned up and provided with a manhole. A six-inch intake was set in a concrete wall at the lower end of this stone-lined section from which water was carried 185 feet through a two-inch pipe to the upper meadow pool, supplying water to stock. The cut had been backfilled and landscaped. Pipe had also been installed to carry water from the fort ponds to the campground and utility area to irrigate trees. A pipe supplying water from the main spring to roadside was installed to accommodate the public. No work was done to any of the buildings. The total cost of all projects was $2,207.50 in labor and $138.15 in "other," or a total of $2,345.65. [861]

67. View of Pipe Spring landscape, looking west

toward the fort, 1934

(Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 367).

Development planning for the monument continued, with Cowell working under the direction of Chief Architect William G. Carnes, Branch of Plans and Design. In late April 1934, Cowell reported the state of developments at Pipe Spring. He recommended that the irrigation system be extended to cover more of the proposed utility area and the comfort station site. A sewage system was needed, along with completion of all other projects begun under the CWA program. His cost estimates for completing all work (water and sewer systems, roads, fencing, grading, cleanup, drainage, and engineering) was $4,639. [862]

As mentioned, development plans called for the removal of the Heatons' store from its location south of the fort ponds as this area was to be used for visitor parking. In June Heaton informed Assistant Superintendent Hugh M. Miller at Southwestern National Monuments that he wished to move the store and gas pump "to a point just opposite from the road that leads to the campground site." [863] The Heatons planned to enlarge the store at its new site and Grant Heaton sought renewal of his permit. In mid-July, however, Superintendent Pinkley turned down the application to operate the store and gas station due to insufficient traffic at the monument for the previous two years and undemonstrated visitor need. [864] The exact date of the store's removal is unknown, but by April 1935, Heaton reported it had been removed. [865] In a recent interview, Grant Heaton confirmed that the store was torn down and not moved. [866]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi5a.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006