|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

PART II - THE CREATION OF PIPE SPRING NATIONAL MONUMENT (continued)

The Heatons Have Second Thoughts

One of the most unusual circumstances surrounding the creation of Pipe Spring National Monument is the fact that by the time the monument was officially established, Mather had not formally worked out the terms of how the Pipe Spring tract was going to be purchased from the Heaton family. [456] The fact that he proceeded with having the monument established prior to the government obtaining legal ownership is evidence of the high level of confidence he placed in the cooperative actions of other interested parties, including the Heatons, Union Pacific supporters, Church officials, and the Office of Indian Affairs. (What appears to have driven his sense of urgency in the matter, as mentioned earlier, was the timing of President Harding's trip and the trip to Pipe Spring by a congressional delegation immediately following this trip. Mather wanted the monument established in order to appeal to this delegation for funding the fort's restoration.) The Pipe Spring property remained under the private (albeit disputed) ownership of Charles C. Heaton for another 11 months after the monument's establishment. What Mather could not have foreseen was the mounting level of antagonism and distrust between local cattlemen and the reservation's Superintendent Farrow, primarily (but not exclusively) over the issue of water. While relations had never been very good, tensions were most certainly heightened during the early 1920s due to the frustrated efforts of the Heaton family and several others to obtain legal title to thousands of acres within the reservation and their foot-dragging at the Agency's demands that they remove fencing from those lands. [457]

A series of events transpired within months of the monument's establishment which very nearly threatened to capsize all the carefully laid plazns of Director Mather, Church officials, and Union Pacific representatives to establish Pipe Spring National Monument. The terms for sale of the Pipe Spring tract had been established during Mather's September 1923 meeting with the Heatons at Moccasin and Pipe Spring, referenced earlier. The Heatons wanted to preserve the monument along with the cattlemen's water rights, but weren't willing to entirely give the property away. The Heatons promised to contribute $500 toward the $5,000 price tag "provided the people of Kane and ashington Counties will donate $500," stated the agreement; "If the $500 is not raised from the Counties, the Heatons will stand the whole $1,000." It is clear that the Heatons were willing to make a significant sacrifice, both to see the site made into a monument and to see the property not fall into the hands of the Indian Office, which was sure to happen if they lost their case on appeal. The Union Pacific System contributed $1,000, as did the Church. Mather gave $500 of his own personal funds toward the purchase. The challenge was to raise the additional funds. Mather had approached both Lafayett Hanchett and President Heber J. Grant to ask for their assistance. While the two men were largely successful, only $3,000 had been collected by December 5, 1923, when Union Pacific made its $1,000 contribution. Still $500 short of the goal, Mather wrote to Ole Bowman of Kanab to inquire about donations from Kane and Washington county cattlemen. [458] Bowman replied that he was unaware that anything was being done to raise the money. [459]

About the same time, Charles C. Heaton learned the final $500 had not been raised. He then informed President Grant that he was willing to donate the cattlemen's $500 in addition to the $500 he had pledged. He also told Grant that he had drawn up a quitclaim deed by which the National Park Service would get two-thirds of the Pipe Spring tract while the remainder would be held by local ranchers, "that is one-third of the water and enough land for corrals in handling cattle." [460]

This was an unexpected turn of events. Why was Heaton going back on the September 1923 agreement and setting new conditions for the sale of Pipe Spring? It appears that Heaton and the other cattlemen had reason to suspect that Dr. Farrow, staunch representative of the interests of the Kaibab Paiute, intended to terminate the cattlemen's rights to water from Pipe Spring at some point in the near future. Heaton was simply trying to insure that the upcoming sale and transfer of title to the federal government did not compromise the cattlemen's interests regarding stock water and corrals at Pipe Spring. The agreement made at Pipe Spring in September 1923, whereby Mather acknowledged the cattlemen's right to one-third of the water at Pipe Spring, was no longer sufficient guarantee for Heaton and the stockmen, given the threats they perceived in Farrow's actions.

The land division proposed by Heaton's description of the quitclaim deed surprised President Grant who notified Mather of Heaton's change of mind. Mather telegramed Grant on January 4, 1924, to say Heaton had evidently misunderstood the water agreement they had made. The Park Service wanted a deed for the entire 40 acres without additional conditions. Mather instructed Grant to "please defer payment." [461] Mather was unable to attend to the Pipe Spring matter for another month, due to other work and travel. Upon his return in February, Mather wrote Heaton to firmly reject his new proposal while attempting to reassure Heaton about his concerns.

I have been out in California for a month or two on Park matters and find on my return that things have not finally been settled up as regards the relinquishment of Pipe Springs and the payment to you of the $4,000 by President Grant. Of course, it will be necessary for you to give a clear title or relinquishment for the entire Pipe Springs ranch, not the two-thirds as stated 129.in your letter to President Grant. The United States could not accept partial title to this property.

I plan to work things out so that the cattlemen could use the water of Tunnel Spring as they have been doing. As regards corrals for handling cattle, our plan, as you remember, was to carry the water down some distance away from the buildings so as to avoid the necessity of having corrals at their present location where they would interfere more or less seriously with tourist travel. At the same time, [they] would take away from the attractiveness of the spot after it was properly developed.

As regards the pipeline, you will remember that we figured that the water could be handled better if it was carried down a mile or two. [462]

Charles C. Heaton responded to Mather on February 29, 1924, saying that he was only trying to make sure the cattlemen got their one-third share of water. He asked if a public water reserve could be set aside to ensure the cattlemen's access to water from tunnel spring. [463] (On May 31, 1922, Secretary Albert B. Fall had adjusted the boundaries of Public Water Reserve 34, created April 17, 1916. [464] ) Mather responded to Heaton on March 13, promising to take up the matter of a public water reserve with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He hinted, however, that the matter could be complicated as public water reserves could only be created on public lands. Heaton was requesting one be established on reservation lands.

On the same day (March 13, 1924), Mather requested that Commissioner Burke amend the executive order which established the Kaibab Indian Reservation so that a water reserve could be located where Heaton wanted it. [465] On April 8, 1924, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs telegraphed instructions for Supervising Engineer C. A. Engle of the U.S. Indian Irrigation Service in Blackfoot, Idaho, to make an official trip to the Kaibab Indian Reservation. Engle made a two-day visit (April 27-28) and there "investigated conditions affecting the establishment of a proposed public watering place near Pipe Spring." In his five-page report, Engle gave a largely confused and inaccurate historical summary of the property's ownership:

Some time prior to 1888, Pipe Spring and the adjacent land came into the possession of an individual named Valentine and since that time, claims to this tract have been based on the 'Valentine Scrip.' It is doubtful whether there has been such settlement or continuous use of these premises and springs, as to constitute a legal and valid claim to the property, on the part of anyone other than the Indians. As indicated above, it is now, and has been since 1907, part of the lands withdrawn for the Kaibab Indian Reservation....

Mr. Charles C. Heaton, who claims Pipe Springs, Moccasin Springs and a large portion of the Kaibab reservation, has suggested to Director Mather of the National Park Service, that a portion of the Indian reservation a short distance southwest of Pipe Springs be set aside as a public watering reserve. In this connection he suggests the use of Tunnel Springs as a source of supply 130.for the proposed watering place. The land referred to by Mr. Heaton is within the most desirable portion of the reservation not yet claimed by the Heatons and the Tunnel Springs, suggested as a source of water, has been developed by Superintendent Farrow, at considerable expense, for the use of the Indians engaged in stock raising, and also for some white lessees holding grazing permits on the reservation. [466]

Mr. Heaton objects to the use of Pipe Springs and the 40 acre tract for a National Monument as provided for by the Presidential proclamation of May 31, 1923, claiming to have sold a portion of it on August 28, 1920, to stock growers for corral purposes. [467] He therefore suggests the use of another tract of land, as above indicated, to which he at this time, makes no claim.

We are firmly of the opinion that under no circumstances should the proposed public watering reserve be established within the Kaibab reservation. More than 4,000 acres, constituting the most valuable portion of the reservation, and including practically all of the springs, which are the only sources of water supply in this country, are already claimed and used and virtually owned by white people. To take from the Indians any additional land, and especially any of the water supply that has been developed on land not claimed by whites, would constitute a grave injustice and would only lead to endless friction and trouble and possibly to violence between the whites and the Indians...

If the cattlemen have a vested right in this water on the Indian reservation, it should be conveyed to a watering place by means of a pipeline to a point entirely outside and at some distance from the reservation boundary, as indicated on the attached sketch. [468]

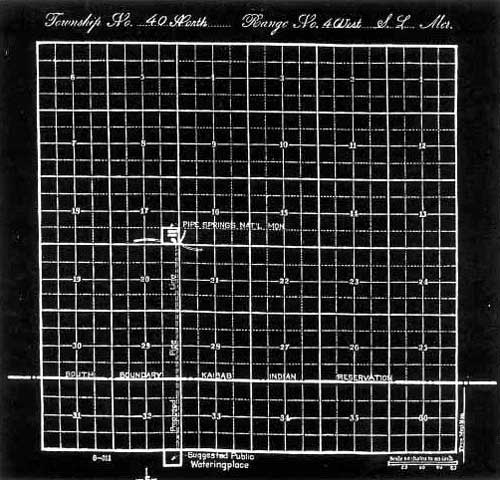

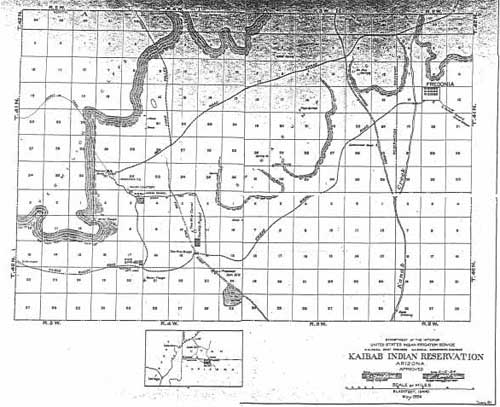

Engle recommended that water be piped at least a mile outside the reservation boundary to minimize the possibility of conflict between Indians (or their Agent) and stockmen. A map of the Kaibab Indian Reservation was also produced in connection with Engle's trip and is shown in figure 34.

34. Sketch map showing suggested watering place

for local non-Indian cattlemen, May 1924

(Pipe Spring National Monument).

35. Map of Kaibab Indian Reservation, May 1924

(Courtesy Bureau of Indian Affairs).

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window - ~121K)

Engle's recommendations were as follows: 1) that immediate steps be taken to "secure a decision as to the ownership of Pipe Springs;" 2) that the rights of the claimant (if proved) be purchased "at any reasonable price;" 3) that the monument be enclosed by a suitable fence; 4) that all water at Pipe Spring "not needed for use in connection with the National Monument be made available for the Indians at Kaibab Reservation;" 5) that the proposed watering place ("the necessity of which is considered doubtful") be established outside the reservation, at least one mile from its boundary at the stock growers' expense; and 6) "that any future proposals to further decrease the size of the reservation and especially to surrender a drop of water originating on the reservation, be firmly rejected." [469]

Engle investigated establishment of a water reserve at Pipe Spring on April 27-28, 1924. Charles C. Heaton executed a quitclaim deed for Pipe Spring to the United States of America on April 28, 1924. Also on this date Heaton withdrew the pending application to locate Seegmiller's Valentine scrip certificate No. E-13 that the Pipe Springs Land & Live Stock Company filed earlier. (The two documents are provided as Appendices IIIa and IIIb of this report.) This is the second, extremely intriguing coincidence of dates that occurs in the Pipe Spring story. [470] Had Engle made his views known to Charles C. Heaton about his opposition to creating a public water reserve at Pipe Spring? Did he share any of his other views with Heaton, all of which were strongly in favor of protecting the rights of the Kaibab Paiute? Was Heaton aware that Engle's report recommended that the Office of Indian Affairs pursue legal ownership of PipeSpring? Did he know that should the Indian Office fail in its attempts to acquire Pipe Spring for the reservation, that they were advised to insist that all water at Pipe Spring not needed for national monument purposes be turned over to the Indians? There is no written evidence that Heaton knew of Engle's views or of the recommendations he intended to make. However, something caused Heaton to finally act, to turn the property over to the National Park Service, in spite of ongoing (and still unresolved) concerns he had expressed to President Grant and Director Mather in December 1923 and early 1924. While Heaton had only the September 1923 agreement to pin the cattlemen's "hat" on, had Engle been successful in encouraging the Office of Indian Affairs to pursue certain goals advantageous to the Kaibab Indian Reservation, the Heatons and the cattlemen would have lost all.

While at Moccasin, Engle examined other conditions pertaining to the reservation and prepared a separate report that he submitted to the Commissioner a day after his first report, on May 14, 1924. Engle's final conclusions to his report are highly illustrative of the challenges faced by the Kaibab Paiute, the U.S. Indian Irrigation Service, and the Office of Indian Affairs with regard to the Kaibab Indian Reservation. These conditions would also be those faced by the National Park Service after it took on the administration of Pipe Spring National Monument. Engle made the following observations:

Many of the Indians on this reservation are thoroughly disheartened, and have lost faith in the desire of the government, and the power and ability of the government, to protect their rights.

Various officials informed them, at the time of the Withdrawal Order of October 15, 1907, and again at the time of the promulgation of the Executive Order of July 17, 1917, that the land included within the boundaries of the reservation was their undisputed possession. Failure on the part of the government to fulfill these promises has caused these Indians to lose faith in the government and has caused lack of respect and confidence in the government officials. Many of them are of the opinion that their reservation will gradually fall into the possession of their white neighbors.

In this connection is should be borne in mind that the Indians lived at or near Moccasin Springs for a long time after the coming of the white settlers, and only moved away when they were forced to do so.

Present conditions and past experience seem plainly to indicate that the Heatons will, in a very few years, be in entire control and virtual possession of the entire reservation by gaining control of the water resources, most of 134.which they already claim or use. It is manifestly a question of either the government or the Heatons vacating.

The fact that the first white settler at Pipe Springs was killed by the Indians, and that it was necessary for later settlers to construct a fort for protection against the Indians, would seem to indicate that the Indians did not willingly submit to the conquest of their lands and springs. [471]

Even though Charles C. Heaton signed the quitclaim deed conveying Pipe Spring to the United States of America in late April, this legal document had yet to be turned over to the government. Mather sensed that immediate action was needed to keep his plans on track and on May 25, 1924, he directed Superintendent Pinkley to go to Pipe Spring in early June. Mather then informed Heaton of the objectives of Pinkley's visit: "Pinkley is going to look into the question of the water hole pretty thoroughly and talk over matters generally with you, as well as seeing the cattlemen and finding out what they will do toward running the water from Pipe down to the proposed water hole and corrals." [472] Mather informed Heaton that Pinkley "may be accompanied by one or two others." He chose not to tell Heaton that Pinkley also planned to meet with Dr. Farrow.

Director Mather had his driver, Walter Morse, drive from Barstow, California, to Needles where Morse met Pinkley on June 1, 1924. (The men were there to investigate the proposed new monument of Mystic Maze.) The following day the two men drove to St. George where Pinkley met with Joseph Snow. Upon Mather's instructions, Pinkley discussed with Snow the general road situation, the Rockville cutoff, and the Pipe Spring water matter. While in St. George, Pinkley received a telegraph that William Reed, chief engineer of the Indian Irrigation Service, would be leaving Washington, D.C., for Cedar City the next day to attend the meeting at Pipe Spring. Pinkley stalled for time in Hurricane and at Zion National Park investigating road matters and trail development. On Saturday, June 7, Morse and Pinkley met Reed at the Cedar City train depot. Dr. Farrow had also driven up from Moccasin in his Ford to meet Reed. Pinkley, Reed, Morse and Farrow dined that evening in the El Escalante Hotel, spending the night in Cedar City. It was decided that the following morning Farrow would drive back to Moccasin alone and that the others (now including Randall L. Jones) would take the Packard and stop at Zion en route to Pipe Spring.

After arriving at Pipe Spring, the group looked around for an hour, then dropped Reed off at Dr. Farrow's office. Jones, Pinkley, and Morse spent the night in the home of Charles C. Heaton. Reed spent the night with the Farrows. Pinkley later wrote Mather of his visit, "I need hardly detail to you the pleasure it was to meet the Heatons, because you have met them yourself and know what fine people they are. We sat up until nearly eleven o'clock that night and then arose early in the morning to resume our talk." [473]

The next morning at nine o'clock (now June 9, 1924), all the men met at Pipe Spring to thresh out the issues. The cattlemen had a five-year permit to graze cattle on the reservation with three years yet to run. Reed said he was not opposed to the cattlemen using tunnel spring water for the life of their grazing permit, but beyond that would not comment. During negotiations, Pinkley determined that Farrow intended to cease issuing cattle permits at the end of the three years and to use the water from Pipe Spring for irrigating Indian lands. He asked him outright if that was the case and Farrow admitted that it was. This revelation frightened Charles C. Heaton, who then could see that any pipeline serving the cattlemen's needs would have to go completely outside the reservation boundary. Reed suggested they go back to Farrow's office to go over records, which they did. (It is doubtful that Heaton accompanied the officials.) Pinkley later reported to Mather,

It was at this time that Dr. Farrow turned his heavy artillery loose by attacking directly the right of the President to legally proclaim the Pipe Springs a national monument. His argument is based on a rider, which he says the Interior Department appropriation bill carried in 1921 or 1922 to the effect that Indian reservation boundaries should not thereafter be changed by executive order. He had already hinted at this once before when we were talking in Cedar City, and I feel sure from the way he talked about it that he is sincere in his belief. Whether he is correct or not I do not pretend to say, but it might be worthwhile to look into the matter and see what there is at the bottom of it, for the Canyon de Chelly lies on an Indian reservation and it looks like we may be asked to make a monument in there in the near future.

Dr. Farrow is very sincere in his belief that the Indian rights are being abused by the white man. The white men seem to have been running cattle on that range since about 1861 and the Indians had no cattle until some time after 1900 when the Government bought them some. By right of use, then, I should think the white men have the prior right to use Pipe Spring for watering cattle. [474]

At some point, Charles C. Heaton told Superintendent Pinkley and Chief Engineer Reed that if the cattlemen could pipe the water from tunnel spring through the reservation to the public domain they would be satisfied. Unfortunately, due to the low price of cattle and having had a bad year, the cattlemen would be unable to raise funds to build the pipeline, reported Heaton. After further discussion, agreement was finally achieved. Pinkley drew up a memorandum to make it official. Dated June 9, 1924, the memorandum states:

At a conference held upon the ground at Pipe Springs, located on the Kaibab Indian Reservation, at which representatives of the National Park Service, of the cattlemen's organization, of Mr. Heaton (claimant of Pipe Springs), Mr. Jones of the Cedar City, Dr. Farrow and Mr. Reed were present.

The object of this meeting was to arrive at a satisfactory arrangement concerning the use of water from Pipe Springs by the aforesaid association of cattlemen. It was the consensus of opinion and practically agreed upon by those present as being a fair and just solution of the situation that the cattlemen had the acknowledgement of all parties present to an ownership of one-third 136.the waters from these springs and since a permit exists over the adjacent portion of the Indian reserve that they have the right to conduct water to and upon any portion of the land covered by permit during the life of that permit and at the expiration of the permit, if said permit is not renewed, to conduct the water off the reservation. [475]

Pinkley, Farrow, Reed, Jones, and Charles C. Heaton signed the agreement. (While Jones identified himself on the agreement simply as "Citizen," he had ties to the state and local governments, to local business interests, and to Union Pacific.) Charles Heaton represented the interests of the Heaton Brothers of Moccasin (Charles C., Fred C., Christopher C., Edward, and Sterling) and 12 other parties: The Bulloch Brothers, Lehi Jones, and John A. Adams of Cedar City, Utah; Heber J. Meeks and B. A. Riggs of Kanab, Utah; David H. Esplin and Ed Lamb of Orderville, Utah; and E. Foremaster, John Schmutz, John Findlay, Mrs. Andrews, and Ben Sorenson of St. George, Utah. [476]

Superintendent Pinkley considered his Pipe Spring trip a complete success. The objections Dr. Farrow had raised about the monument's establishment, however, created sufficient doubt in his mind so that he wrote the following in his report to Mather: "I told Mr. Heaton that he had probably better hold the papers which you had sent him until he heard from you, thinking that you might want to clear up the question of the legality of the proclamation making the monument before any money was paid over." [477] Pinkley's report was received and promptly responded to by Acting Director Arno B. Cammerer who replied,

The question brought up by Dr. Farrow as to the right of the President to create the Pipe Spring Monument has been looked into. The act of Congress making appropriations for the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1920, approved June 30, 1919, (41 Stat., 3), contains the following provision: 'That hereafter no public lands of the United States shall be withdrawn by Executive Order, proclamation, or otherwise, for or as an Indian reservation except by act of Congress.' I think this is what Dr. Farrow had in mind, as there is no similar reference in the Indian appropriation acts for 1921 or 1922. This provision does not prevent the setting aside of a national monument within an Indian reservation by Presidential proclamation as contended by Dr. Farrow, and this is the informal view of the Chief of the Land Section of the Indian Bureau with whom this matter was discussed this morning. Had this question been involved it would have unquestionably have been brought out by the Indian Office at the time the Pipe Spring proclamation was prepared. The monument proclamation was approved by the Indian Office before it was submitted to the Secretary to the President for signature.

In closing I want to congratulate you on the manner in which you handled this rather difficult situation, as the solution worked out is probably the very best that could be accomplished in view of the circumstances. [478]

Conflict over water was not the only source of antagonism between the Indian Agency and the Heatons. Since late 1922, the Office of Indian Affairs had pushed for the Attorney General to take legal action to force removal of unlawful fencing on reservation land. Documentation suggests that efforts toward this end intensified during 1924. On June 25, 1924, in response to a request from the Attorney General, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Francis M. Goodwin sent him a description of the lands within the Kaibab Reservation which were unlawfully fenced by "Charles C. Heaton, et al, of Moccasin." Two areas were fenced, each enclosing a certain amount of cliff. Goodwin stated that the area enclosed by the fencing, including the cliffs, was "something in excess of 4,000 acres of land. [479] As mentioned earlier, the fencing was removed in 1925. [480]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi2k.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006