|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

PART II - THE CREATION OF PIPE SPRING NATIONAL MONUMENT (continued)

The Impact of Auto Touring on Utah's Southern Parks and the Arizona Strip

The first automobiles in the United States were produced just prior to the turn of the century. At first considered a luxury, rapid technological improvements and Henry Ford's mass production methods soon made them available to the middle class. The advent of the automobile dramatically changed the nature of tourism in the American West. No longer dependent on the stagecoach or the railroad to reach one's destination, travelers with the incredible "horseless buggy" could now strike out courageously at a moment's notice and tour the countryside to their heart's desire. Edwin Gordon Woolley did just that in June 1909. (Woolley was a son of Edwin Dilworth Woolley, Sr., former manager of the Pipe Spring ranch.) Woolley drove with his wife and brother-in-law, D. A. Affleck (who drove a second auto), from Salt Lake City to Kanab. There they picked up Edwin G. Woolley's half-brother, Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., and Graham McDonald, then they took off for the Grand Canyon's North Rim. Three days later, they arrived at Bright Angel. "Indians came from miles around to see their first 'devil wagons,' which they were loath to believe could run," wrote Angus M. Woodbury about the event. [336] The Woolleys envisioned the wealth of development opportunities that would arise, if only good roads could be built and auto-owning tourists could be enticed into venturing across the desolate Arizona Strip! The U.S. Rubber Company, "to demonstrate the wonderful performance of their product," later proudly displayed the nine tires they wore out on their journey. [337]

Utah politicians could also see the potential for tourism to revive the state's agricultural economy, which plunged into a serious depression after the "boom" years of World War I. [338] Senator Reed Smoot introduced a bill to establish Zion National Park (previously Mukuntuweap National Monument) on May 20, 1919. The bill was passed by Congress, and was signed by the President on November 19, 1919. Stephen Mather was in Colorado's Rocky Mountain National Park for the fifth annual conference of superintendents when word came that Zion National Park had been established. At Albright's urging, Mather made his first visit to the area. He became enamored with the park, returning every year for the remainder of his life.

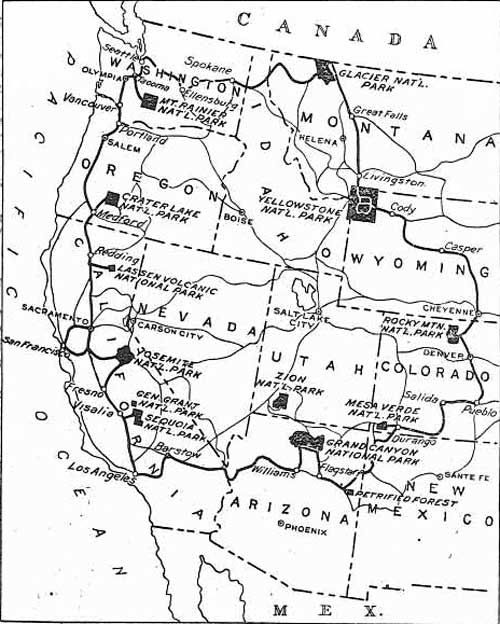

One of the most notable accomplishments of the good-roads movement, in relation to the national parks, was the August 1920 establishment and designation of a great, connected highway between the major national parks of the Far West. The purpose of the National Park-to-Park Highway was three-fold: 1) to make scenic areas more accessible to the public, 2) to aid further development of the West by bringing its industrial resources to the attention of the traveling public, and 3) to attract new settlement. The National Park-to-Park Highway Association (NPPHA) accomplished the undertaking, in cooperation with the American Automobile Association (AAA) and other western organizations. The official designation tour began in Denver, Colorado, on August 26, 1920, "at which time," Stephen Mather reported, "I formally dedicated the National Park-to-Park Highway with appropriate ceremonies to the American people." [339] The 4,700-mile-long circle tour passed through nine western states, crossed every main transcontinental highway and touched most of the north and south highways west of the Rocky Mountains. The only parks in the southwest included on this route were Mesa Verde, Petrified Forest, and the Grand Canyon's South Rim. Mather envisioned the Park-to-Park Highway as "but a nucleus of a great interpark road system which will be developed later on." [340]

22. Map showing National Park-to-Park Highway and

interpark road system

(Reprinted from Report of the Director of the National Park

Service, 1920).

In conjunction with the dedication of the highway, a National Park-to-Park Highway conference was held in Denver, Colorado. Utah's Governor Simon Bamberger sent Randall L. Jones as its representative. (Jones was an architect and a native of Cedar City.) There, plans were laid to coordinate the local movements for good roads into a park-to-park system. The NPPHA and AAA continued to hold annual conferences each year in various western cities. By 1923, thanks to their efforts and those of chambers of commerce, boards of trade, and other local civic organizations, the "great circle route" had expanded to 6,000 miles and included 12 national parks. [341] The NPPHA's objective was to hard surface the entire route (only one-fourth of this length had been "permanently improved"). In support of the work of the NPPHA, the National Highway Association offered in 1923 to print maps depicting the National Park-to-Park Highway for public distribution by the Park Service.

While the nation wide effort to provide a highway to link national parks was growing, state and local officials in Utah and Arizona were well aware of the need for local road improvements. Without them, the vast majority of motorists would visit only the most well known and easily accessible of the parks. In the early 1920s, most of Zion National Park's visitors were Utah residents, folks long accustomed to the terrible conditions of rural roads. To reach Zion from the east, travelers drove down through central Utah to Fredonia in northern Arizona, then, passing Pipe Spring, westward to Hurricane "on a mere faint trail where there was some danger of getting lost and perishing," wrote historian John Ise. [342] There was a rough road from Hurricane to Rockville and to Zion's entrance. Even the best of roads and bridges were susceptible to washouts from flash floods, making a well-planned road trip still a gamble during some seasons. If one was spared the fate of washouts and of having one's vehicle mired in the tire-clenching "gumbo" created by rainstorms, a road trip through many parts of Utah or Arizona in those days was always accompanied by a steady diet of dust.

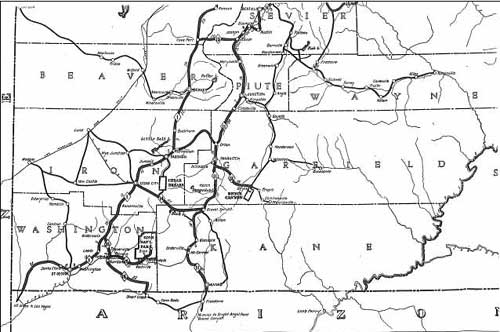

23. Map detail, Utah State trunk Lines, State Road

Commission, 1923

(Courtesy Union Pacific Museum).

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window - ~89K)

In his 1923 annual report to Congress, Mather wrote that more than 60 percent of park visitors came in their own private automobiles. [343] A detail from the following map produced by the Utah State Road Commission and dated 1923, shows existing roads in Iron, Garfield, Washington, and Kane counties (as well as the Hurricane-Fredonia road) in 1923. Also depicted is the Union Pacific's Los Angeles and Salt Lake City Railroad line passing through Lund with its newly constructed spur line to Cedar City. (Pipe Spring National Monument is not shown on the map, perhaps because it was located in Arizona or because the map was produced prior to the establishment of the monument.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi2a.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006