|

Nez Perce National Historical Park |

|

Big Hole National Battlefield |

|

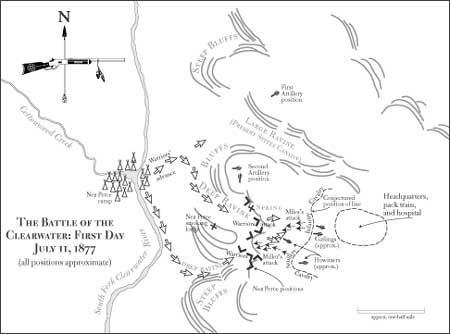

Chapter 4: Clearwater (continued) In the meantime, warriors from the camp crossed the South Fork and began a spirited approach through two large ravines leading to the bluff tops along which Howard's troops marched. (These ravines were opposite of and south from the village; they ran east on either side of the feature today called Dizzy Head.) When shooting by the Indians erupted behind and to the left of the column, Howard—anxious to join the battle after consecutive debacles—first countermarched his men, then deployed them into line to return fire on the warriors. Captain Miller placed his companies "along the crest of a ravine to the right, to connect on the left with the Infantry." [26] Wrote Second Lieutenant Charles E. S. Wood, of the infantry: "It was a test case—all the hostiles under Joseph against all the soldiers under Howard." [27] Back at the north, on orders to move to the main body, Trimble's Company H, First Cavalry, which was as much as one-half mile in front of the column, dismounted and, leading their horses, turned back and encountered Captain George B. Rodney and Company D, Fourth Artillery, who were escorting the pack train. [28] Placing the animals between the two units, Trimble and Rodney passed through the depression at the head of the ravine (present Stites Canyon) to gain the open plateau on which the balance of the column was deploying into a rough semicircle, with the curve facing the bluffs. As Trimble and Rodney extended their men into the line, the pack animals proceeded several hundred yards to the rear and center, where Howard established his headquarters and hospital and where the other cavalry animals had been sent. One officer recalled that the headquarters was built "with the aid of the Pack Saddles piled in a circular manner, though the protection was very slight." [29] The Nez Perces who confronted Howard's troops had been taken by surprise. Many had been engaged in routine activities in the camp. Some were racing ponies on the flat land along the river bottom north of the village and others were swimming in the South Fork, when the booming of the howitzer and the crash of the shells fragmenting caught their attention. A scout came riding down the hill east of the river and announced that the soldiers were surrounding the camp. Twenty warriors grabbed their weapons and cartridge belts, then fell in behind Toohoolhoolzote, the aged leader who Howard had jailed at Fort Lapwai. Together, they raced upstream about one-half mile to a shallow ford, then crossed and ascended the ravines to attack the troops and keep them from approaching the camp. Tying their horses in the trees, the warriors crept along the brow of the bluff, occupying several points between the spring and the large draw up through which most of them passed. Armed with an old muzzleloading rifle, Toohoolhoolzote crawled up the slope and killed two soldiers, among the first to fall in the battle. Other warriors piled loose stones into crude ramparts, then moved ahead, fired at the troops, and fell back behind the barricades. Because the troops had miscalculated the location of the village, they had actually passed on toward Clear Creek before discovering their error, and it took them time to reverse direction and march back to the blufftop plateau, where they were when Toohoolhoolzote attacked and caused them to assume their defensive line. While this initiative held the soldiers in place, more warriors—having moved their families from danger—now swept into the large ravine and gained the heights. Many of them followed the military leaders, Rainbow and Ollokot. The total number of fighting men at the top at this time probably did not exceed one hundred. [30]

As the principal Nez Perce firing settled in the large ravine below the blufftops on the south, Howard's men adjusted their own position. Miller with two infantry companies, plus Company A and part of Company E of the artillery, withdrew toward the sound of the gunfire. The roughly skewed, crescent-shaped defensive perimeter of the soldiers fluidly settled into place to meet the warriors. From its southernmost extremity to its northernmost, the command deployed as follows: Companies F and L, First Cavalry; artillery battalion; infantry battalion; Companies E and H, First Cavalry. Before long, about twenty-five warriors appeared on the south end of the perimeter, galloping as if to flank the troops. Instantly divining their plan, Major Edwin C. Mason of the Twenty-first InfantryHoward's chief of staff who was supervising the placement of troops—took Burton's and Second Lieutenant Edward S. Farrow's Companies C and E, emerged from the line, and with Captain Winters's cavalry on their far right, moved ahead "under a hail of fire" to disrupt the movement. Meanwhile, two civilian packers and their laggardly pack mules loaded with howitzer ammunition hove into sight from the south, hurrying to reach the command. When within three hundred yards of the skirmish line, the warriors dashed in, killed the two men, and moved off with three of the animals and their baggage. [31] Fire from Perry's and Whipple's cavalrymen helped dissuade the attackers, and soon Lieutenant Wilkinson, aided by Rodney's company, arrived to escort the remaining mules into the line. [32] All this time, the gunfire from the edge of the bluffs—and especially from the Nez Perce position in the forested gulch opposite Howard's left—continued to increase in volume, as the warriors sent a barrage of bullets among the troops. "They gave it to us hot," said one observer. Supplementing the soldiers' rifle and carbine fire was that from the howitzers and Gatlings commanded by Lieutenant Otis, for the moment still stationed at a pivotal site on the bluff and capable of dominating both the village and the principal Nez Perce position in the ravine. [33] Eventually, one howitzer, then the other, was drawn up behind the left of the line and nearly opposite this latter position. [34] Occasionally, the warriors attempted assaults on this front. These charges were made "in regular daredevil style, nothing sneaking about it," remembered Sergeant McCarthy. "They were brave men, and faced a terrific fire of musketry, gatling [sic] guns and howitzers." [35] One attack came from a ravine opposite the right of the line in which a spring was located. (This draw is presently called Anderson Creek Ravine.) Several men of Company B of the infantry resisted this assault, during which Private Edward Wykoff was killed and another man was wounded. McCarthy recollected details of the warriors' attacks:

About midafternoon, the warriors opened an attack on the left front of the army line. Captain Evan Miles led Companies B, D, E, and H, of the infantry, and A and part of E, of the artillery, in a spirited drive that cleared some of these tribesmen from the ravine. A Civil War veteran of marked ability, Miles had served with the Twenty-first since 1866. [37] Captain Marcus P. Miller and the balance of the artillerymen supported Miles's movement, in which Captain Eugene A. Bancroft, Company A of the artillery, was shot through the lungs and Lieutenant Charles A. Williams of the infantry through the wrist and thigh. [38] Miller described the action:

A correspondent told of Miles's action:

Although the artillery pieces played on the Nez Perce positions, the warriors managed to kill or wound four members of one howitzer battery. Private William S. LeMay, the sole remaining cannoneer, was able—by lying on his back between the wheels—to load and fire the weapon and drive back the warriors. [41] So determined were the warriors that, at one point, they practically enveloped the howitzer and Gatling. First Lieutenant Charles F. Humphrey quickly gathered some men of Company E, Fourth Artillery, and facing a blistering fire from the warriors, retook the pieces, the soldiers having to haul them manually. Captain Miller reported: "That party had to cross grounds seen to be exposed to severe fire from the Indians—but following the example of Lieut. Humphrey the men went bravely on. Two of them were wounded in getting there." [42] But Humphrey's maneuver seemed to determine the warriors in pressing their attack, and they continued their push toward the battery. Many army casualties happened at this point. As one observer reported:

The dead lay where they fell; wagons took the wounded to the hospital, where the surgeons had raised an awning for their comfort. The warrior Yellow Bull claimed that the warriors had planned to capture some of the soldiers alive. One named Pahatush prepared to go out. "Just as he was about to start, a volley was fired by the soldiers, and the smoke was so thick that we could not see. Pahatush was shot in the right hand as he held his gun, and the gun was broken." [44] Soon afterward, forty-two-year-old Captain Miller led another charge on the bluff to the immediate right of the ravine held by the greatest number of the warriors. According to Miller,

Miller's actions here and on the next day were roundly hailed, and he emerged from the battle a genuine hero. Miller's charge on the Nez Perce positions at Clearwater succeeded in significantly advancing the army perimeter in that critical sector. Correspondent Thomas Sutherland wrote:

Participating in this action were Companies B, C, H, and I, of the infantry, along with Company E of the cavalry. Simultaneously, on the right of the army position, Lieutenant Wilkinson opened a lively demonstration with the remaining available men, while the howitzers leveled a bombardment on the Nez Perces' position. The firing from the right perhaps contributed to the recall of Miller's men from their farthest advance, for it was soon discovered that his soldiers were being fired upon from behind. Seeing what was happening, Second Lieutenant Harry L. Bailey dashing out between the lines—shouted, "Cease firing[!] You are firing into your own men[!]" After a few minutes, order was restored and Miller's troops withdrew several paces back. [47] Bailey recounted an incident that occurred as he scolded one of his men for recklessly exposing himself. "'I tell you, Lieutenant, this is a ticklish business.' I told him it would be more ticklish if he did not keep his place. At that moment a rattlesnake reared up at his elbow, and he forgot the bullets for a second!" [48] Howard concluded the maneuver a success: "Miller's charge gained the ridge [along the bluff top] in front and secured the disputed ravine near Winters's left [present Anderson's Draw]. Further spasmodic charges on the left by the enemy were repelled by Perry's and Whipple's cavalry, dismounted, and Captain Arthur Morris's artillery, Company G." [49] This bold attack by Miller's men succeeded in driving many of the Nez Perces with Toohoolhoolzote away from the brow of the hill. The warrior Yellow Wolf remembered the event. "Indians and soldiers fighting—almost together. We could not count the soldiers. There must have been hundreds. Bullets came thicker and thicker." [50] When the soldiers crested the brow, the warriors dashed away through the trees, many leaving their ponies behind as they moved down the ravine. They evidently returned after Miller's troops pulled back from their farthest advance. Some of the warriors who fought there were later identified as Wahlitits (Shore Crossing), Sarpsisilppilp (Red Moccasin Top), Tipyahlana Kapskaps (Strong Eagle), Pahkatos Owyeen (Five Wounds), and Witslahtahpalakin (Hair Cut Upward). Yellow Wolf later joined a party in the area of the spring, the members of which were engaged in a contest with the cavalrymen on the line. Here, the tribesmen suffered their first battle losses when Wayakat (Going Across) was shot and killed and Yoomtis Kunnin (Grizzly Bear Blanket) received a fatal wound. Another man, Howallits (Mean Man), incurred a slight wound. Here, too, Yellow Wolf was instructed to shoot at officers rather than common soldiers. [51] (The Nez Perces continued to pursue this unique tactic in subsequent engagements with the army.) During the day, one of Howard's Nez Perce scouts deserted the troops. He was Elaskolatat (Animal Entering a Hole), whose father had been killed in the volunteers' fight at Cottonwood. At an appropriate moment, the scout dashed his mount across the field and into the Nez Perce lines, where "he threw off his citizen's clothes and dressed as an Indian for battle." Later that day, while joining in a horseback charge, the former scout received a gunshot wound. [52] |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Nez Perce, Summer 1877 ©2000, Montana Historical Society Press greene/chap4a.htm — 26-Mar-2002 | ||