|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

SITE SELECTION FOR MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER — HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF OWENS VALLEY AND MANZANAR VICINITY (continued)

EARLY HISTORY OF MANZANAR

The earliest Euro-Americans to settle in the vicinity of what would later become the site of the Manzanar War Relocation Center arrived at George Creek, approximately three miles south of the site, in 1862 in search of feed for their cattle. They arrived during the height of the hostilities then occurring between the Indians and whites as the Owens Valley Paiutes attempted to defend their traditional homeland against the encroaching white settlements. Among the settlers was John Shepherd, a cattleman from Visalia in the Central Valley of California who had been born in Illinois in 1833. Attracted by the ranching possibilities of the vicinity, Shepherd built a small cabin near George Creek. [134] John's two brothers, James and George, also settled at George Creek at the same time. Shepherd had come to California in 1852 with his brothers, sailing from their home in North Carolina around the Horn to California. After living in Stockton for a short period, John spent several years in Los Angeles engaging in freighting between that growing city and San Pedro before settling on a cattle ranch near Visalia with his two brothers. [135]

When the settlers arrived, they found a Paiute village of approximately 100 inhabitants. The Paiutes practiced a form of irrigated agriculture supplemented by hunting and pine-nut gathering. [136] The Paiute leader, known to the settlers as Chief George (for whom the creek was named), would later earn the respect of both Indians and whites as a leader and mediator in the efforts to achieve peace between the two groups of people. According to one source, when Dr. S. G. George was prospecting in the area in 1860, a Paiute leader whose camp was on the creek acted as his guide and took the name Chief George. [137]

In 1863 John Shepherd returned to Visalia to move his wife and two small children to his small cabin on George Creek. The following year he homesteaded 160 acres on Shepherd Creek, three miles north of George Creek, on the future site of the relocation center. Shepherd built a small adobe brick home, the bricks being of white plaster made from the alkali found on the east side of Owens Valley. He began a cattle ranching operation and grew alfalfa and grain for feed as well as for sale to the mining camps on the east side of Owens Valley. While George Shepherd would soon leave the valley, James continued to ranch with John at Shepherd Creek. [138]

In 1873 Shepherd built a large nine-room ranch house near Shepherd Creek for his growing family which would soon include eight children. The two-story house featured a balcony and was constructed of redwood brought by wagon from San Pedro, and its elaborate white gabled exterior became a landmark in the valley. The new house was connected to the original adobe brick home, which was used as a kitchen, dining room, and extra bedroom, by a grape arbor. The house resembled a southern Victorian mansion and featured running water in the kitchen. It was surrounded by a grove that included apple, cottonwood, black walnut, willow, and poplar trees, and marble statues and fountains and two basins graced the grounds. Beside the creek was a flume that led to a quaint waterwheel. Shepherd quickly rose to prominence in the area's political and social circles, being elected an officer of the recently established Masonic lodge in Independence in "1873 and a county supervisor in 1874. As a result, his home became a center of social life for area residents and a stopover spot for travelers and teamsters who were housed in the original adobe structure. [139]

An Indian camp and an associated burial ground developed to the west of Shepherd's home above the irrigated portion of the ranch. The camp consisted of tents and shelters made from tule reeds, which housed an unspecified number of Paiutes, most of whom were employed and given land for shelter by Shepherd following their return to the Owens Valley from the forced removal to the San Sebastion Reservation in 1863. [140] There is evidence that Shepherd was sympathetic to the plight of the returning Indians, because he attributed the Indian-white clashes of the early 1860s to white mistreatment, observing that "white people were not treating the Indians right and the Indians finally got tired of it. [141]

By June 1874 Shepherd employed more than 30 Indian women on his ranch, paying them 75 cents a day. [142] The women winnowed grain and performed domestic tasks on the ranch. Meanwhile the Indian men, many of whom were knowledgeable in irrigation techniques, performed irrigation work on the ranch and in 1874-75 helped Shepherd build a toll road from Keeler in Owens Valley to Darwin in Panamint Valley for transporting livestock and farm products to the east. One contemporary source noted:

John Shepherd has completed the toll road from the foot of the lake, via Darwin to the new survey, through the foot of Panamint Canyon, and it is now said to be a splendid road for any kind of teams. Shepherd did most of the work with his Indians under the command of Captain George, and we are told that the way the captain and his men slashed sage brush, and made rocks and dirt move, could not be surpassed by any equal number of white men that ever made road for wages. [143]

As was the custom in the valley, many of the Paiutes at the ranch took the Anglo surname of their employer. This was a sign of respect on the part of the Indians and an indication of the paternalistic relationship which developed as the Paiutes became an indispensable part of the labor force and contributed to the success of the farms and ranches with their knowledge of irrigated agriculture. Additionally, there are many accounts that attest to the respect that the Indians had for Shepherd. [144]

In November 1877, after Camp Independence had been abandoned by the military, leaders of the Paiutes from Bishop Creek, Deep Springs, Big Pine, Fish Springs, and Independence gathered at George Creek. The Indians invited local whites to the meeting and John and James Shepherd and John Kispert attended — as well as a representative from the Inyo Independent. Speaking for the Indians were Captain Joe Bowers and Captain George. They encouraged the other Indian leaders to recognize the folly of "entertaining thoughts of hostility to the whites," and they sought an agreement between the Indians and the whites as to how troubles between them might be adjudicated. If an Indian killed an Indian, he would be dealt with by the Indians. If an Indian harmed or killed a white, he would be turned over to the whites for justice. If a white killed an Indian he would be dealt with by the whites as if the Indian he killed had been white. The newspaper representative noted:

Captain Joe's proposition, given at the outset, was cordially endorsed by all present, and now, it only remains for us to add, that they all most respectfully ask the whites not to get excited or alarmed at the act of any individual mischief maker, to act with moderation in any event, all will be well. [145]

Thus, a truce — or an accommodation — was agreed upon between the Indians and the whites, and peaceful relations developed in Owens Valley.

A fire on the "prosperous" Shepherd farm was reported on July 19, 1879. The fire was attributed to the carelessness of one of Shepherd's Indian laborers. A newspaper article noted:

At about 2 o'clock P.M. Thursday last a fire started near some outhouses and bid fair to sweep all the stacked hay, granaries, stables, etc. At the same moment a Petaluma hay press was aflame, and cinders were flying in every direction; yet by the almost superhuman exertions of Mr. Jas. Shepherd, members of the household and some Indians, the press and all the stacks were saved. The fire originated from some coals and ashes carelessly thrown out by an Indian employed about the place. [146]

Following reported disagreements over water rights With neighboring ranchers, John and James Shepherd eventually acquired many of their properties. By 1881 the two Shepherd brothers owned 1,040 acres having an assessed value of $6310. Improvements on the property had a value of $3,800. Their personal property had an assessed value of $3,925, including four wagons, six work horses, 40 halfbreed horses, 3 mixed blood cows, 15 stock cattle, four dozen poultry, one jack, three mules, 40 hogs, 25 bee hives, and 200 tons of hay. Among other items for which the brothers were taxed included three watches, furniture, firearms, musical instruments, a sewing machine, farming utensils, machinery, and harnesses. The total value of their property was $14,035 on which they paid a tax of $491.22. [147]

By the late 1800s the Shepherd lands were all in John's name, and his landholdings had grown to some 1,300 acres, including a large portion of the future relocation center site, and two-thirds of the Water rights on Shepherd Creek. Shepherd raised cattle, horses, mules, grass, hay, and grain and hauled ore from the Inyo mines to San Pedro, bringing back supplies to Owens Valley. Many of his horses were sold to ranchers in southern California, notably the Bixby family which owned extensive acreage in the Long Beach area.

By 1893 the George Creek and Shepherd Creek settlements included some 28 families, some of whom had mined at Cerro Gordo and other mining strikes. [148] The sizes of the ranches, which featured fertile land and lush pastures, ranged between 160 and 1,700 acres. Most of the settlers of the area had small herds of cattle and bands of sheep as well as vegetable gardens and orchards. Among the fruit raised were apples, pears, peaches, apricots, nectarines, and plums, and cherry trees were beginning to be planted. Corn and wheat were raised, and the average annual yield of the latter was 40-55 bushels. Surplus agricultural produce was sold to the surrounding mining camps or traded at stores in Lone Pine or Independence for staples. The 15-mile-long Stevens ditch had recently been completed from Owens River above Independence to the southern part of the settlement, thus providing additional water for irrigation. [149]

In September 1905, George Chaffey, after visiting Owens Valley during the spring of that year, filed an application for water rights and the right to construct a reservoir on Cottonwood Creek in the southern end of the Owens Valley, intending to use the water for establishment of a hydroelectric project to power an electric railroad to Los Angeles. In October of the following year, Chaffey established Sierra Securities Inc., a firm connected with his extensive banking interests in Los Angeles, to provide financing for the projects he envisioned in Owens Valley. During the next two years, he and his associates transferred to the company all their landholdings and water rights acquired during 1905-06. [150]

Chaffey, a member of a prominent Southern California family that had emigrated from Ontario, Canada, was one of the foremost water developers of his generation and a prime example of the successful engineer as private entrepreneur. In his early years, he and his brother, William Benjamin Chaffey, founded the irrigation colonies of Etiwanda and Ontario in southern California, where they introduced a system for the mutual ownership of water resources which was later widely adopted to open large sections of southern California for settlement. Among other accomplishments, the Chaffeys constructed the first hydroelectric power plant and electric house lighting west of the Rocky Mountains at Etiwanda in 1881 as well as the first western street lights in downtown Los Angeles in 1882. At the request of the Australian government, George, along with several members of his family, established the first two irrigation colonies at Renmark and Mildura. Returning to California around the turn of the 20th century, George and his family established several irrigation colonies in the desert wastes of Imperial Valley, developing these communities by constructing an extensive irrigation system to carry Colorado River water north from Mexico. In 1902, George bought a small water company in east Whittier near Los Angeles and expanded the company's operations to supply water to east Whitter, La Habra, and Brea, thus enabling those communities to become large citrus and avocado producers. During 1901-02, George and his oldest son, Andrew, pioneered banks in Ontario and the Imperial Valley and subsequently in Los Angeles, and as a result he became a major economic force in the real estate boom of the rapidly-expanding Los Angeles area.

Thus, George Chaffey came to the Owens Valley in 1905 to establish his last irrigation project. His interest in the valley coincided with the early announcement of the Los Angeles Aqueduct project and with efforts taken by the City of Los Angeles to secure the right-of-way to large amounts of federally-protected land as long-term protection for its water rights in Owens Valley Nearly 20 years of contentious litigation between Chaffey and the City of Los Angeles would ensue as each sought to implement plans for the area. [151]

Earlier in July 1905, George Chaffey sent his youngest brother, Charles Francis, to Shepherd Creek to purchase the Shepherd Ranch, which by that time totaled more than 1,300 acres, to secure both the land and the water rights to the nearby streams for his envisioned colony. In ill health. Shepherd sold his landholdings to Chaffey for $25,000 and moved to San Francisco where he died on May 14, 1908, at the home of his daughter. Charles Francis moved his wife and six children into the former Shepherd ranch home in September and, after transferring the Shepherd Ranch to his brother in November, he became the first on-site manager of George's extensive landholdings in the vicinity. The family lived in the former Shepherd home until 1907, when Charles moved to a fruit ranch he had purchased near Vancouver, British Columbia. Thereafter, a succession of company farm superintendents took over management of the Chaffey properties in the area and occupied the house. Upon hearing of Chaffey's purchase of the Shepherd property, William Mulholland, who would oversee construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, reportedly told a prospective rancher in the valley that if "Chaffey purchased that ranch," we [Los Angeles] will certainly turn that back to sagebrush." [152]

On May 6, 1910, the Chaffeys and their partners established the Owens Valley Improvement Company to operate their proposed irrigation settlement project. The company, headquartered in Upland, California, had a capital stock of $500,000 divided into 5,000 shares valued at $100 each. [153] Other adjacent properties, as well as ranch lands in the vicinity of Independence, had been acquired by the Chaffeys and their associates since 1905 for a total, including the former Shepherd holdings, of more than 3,000 acres. About this time, a concrete pipe and drain tile manufacturing operation owned by V. C. Lutzow was begun, probably West of the former Shepherd house. [154]

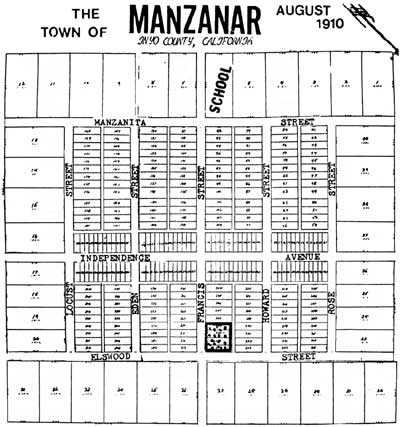

In August 1910 the Owens Valley Improvement Company's Subdivision No. 1, consisting of approximately 1,000 acres, was laid out. A townsite was platted near the center of the subdivided tract (see a copy of townsite plat on page 173), and the initial elements of a system of concrete and steel gravity flow irrigation pipes were installed to bring water to the land parcels from Shepherd and Bairs creeks. The subdivided tract and the townsite were named the Manzanar Irrigated Farms and Manzanar, respectively, since "Manzanar was the Spanish name for apple grove and apples were the most logical crop for the area because of its climate. The tract was advertised by agents in San Francisco and Los Angeles and promoted via brochures that touted the possibilities for success and wealth at the new colony because of its fine soil, abundant water, favorable climate, and proximity to markets. Parcels of 10, 20, and 40 acres were offered for sale at $150 and up [some sources refer to parcels of 16 and 25 acres] and included ownership of one share per acre in the Manzanar Water Corporation, incorporated on September 4, 1915, [155] and the services of a zanjero or water distributor. Where settlers were located on land served by the gravity flow irrigation system, water under pressure was delivered for which a small monthly charge was made. Beyond the irrigation distribution area, domestic wells were sunk, water being obtainable at from 15 to 30 feet below ground level. The Owens Valley Improvement Company's general plan was to develop and expand the valley's apple production, and the firm offered to plant apple trees and care for them for absentee landowners or to sell trees directly to residents. [156]

Subsequent to the summer of 1910, some roads in the Manzanar townsite vicinity were graded, and purchases of the town lots began. [157] A community began to take shape as a two-room schoolhouse, community hall, cannery, garage, lumber yard, blacksmith shop, and store, which also served as the town post office and held the town's only telephone, were built. The nucleus of the Manzanar community was located near a "straight, broad highway," which would later become a part of present-day California State Highway 395, that had been laid out from Independence to Manzanar by 1912. Like the streets of the townsite, the highway was bordered with trees. Later, an ice cream and soft drink stand, known as the "Wickiup," was established along the highway. [158]

Farmers and ranchers, some with little or no previous agricultural experience, arrived at Manzanar from points as distant as Missouri and Indiana, although many came from southern California and western Nevada as well as from the nearby communities of Independence and Lone Pine. While most purchased the property they farmed, some farmed lands for absentee landlords, including an English nobleman Primary agricultural products raised at Manzanar included fruit such as apples (Winesaps, Spitzen, Burgs, Roman Beauties, Delicious, and New Town Pippens), pears, peaches, berries, and grapes; crops, such as alfalfa, corn, and wheat; and vegetables, principally onions and potatoes. Cattle, poultry, and pigs were raised for meat, eggs, and dairy products. Beehives were tended for honey production. [159]

s/

Figure 18: The Town of Manzanar, August 1910 Townsite Plot, Eastern

California Museum.

(click on image for an

enlargement)

By 1912, approximately 20,000 apple trees had been planted at Manzanar. The town boasted a Manzanar Commercial Club to attract property purchasers. The club's president was Ira L. Hatfield, the second man to purchase land in the new development in October 1910. He planted 20 acres of apples, and in April 1911 he constructed the store in town, handling everything from groceries and dry goods to hardware and farm implements. He also "secured the postoffice," which had been located at Thebe since 1896, and opened the new post office in his store on May 30, 1911. At that date Manzanar had a population of 50, but the post office was organized to serve a population of 150, including the residents of the George Creek settlement. The secretary of the commercial club was W. B. Engle, who had purchased land and planted 25 acres of apples at Manzanar in 1911. Aside from ranching, he served as an agent of the Union Central Life Insurance Company of Cincinnati. [160]

Manzanar was Owens Valley's first coordinated attempt at water conservation. In contrast to the methods of irrigation that were employed elsewhere in the valley, the new irrigation system at Manzanar consisted of miles of concrete and tile pipe to prevent seepage and improve drainage. Intake dams were constructed on Shepherd and Bairs creeks. Water was distributed throughout Manzanar via an underground steel and cement system to the high corner of the individual lots. Generally, water to which each stockholder was entitled was accumulated and delivered in large heads every 15 to 30 days. Plans were developed and carried out after 1917 to expand the system of inverted concrete tile drainage ditches. [161]

Initially, markets for the agricultural produce of the Manzanar farming enterprises were the neighboring towns and mining areas in the Owens Valley region. As the mines declined, however, more of the products were transported by railroad, either through Tonopah and Goldfield to northern markets, or southward to Mojave and Los Angeles. The trip south was made in unrefrigerated rail cars and required costly reloading from the narrow to the broad gauge line at Owenyo or hauling to Lone Pine to pick up the broad gauge directly. The Manzanar railroad station — a boxcar — was located at Francis (later the name was changed to Manzanar), four miles east of town. In the early days, a wagon and team of mules made round trips between the settlement and the railroad station for freight and passengers. By the mid-1910s the orchards that had been planted during the early 1910s began to produce fruit harvests. The Manzanar Fruit and Canners Association was incorporated on July 24, 1918, to "conduct and carry on in all its branches the business of canning, preserving, drying, packing and otherwise handling, disposing of and selling all kinds of deciduous and other fruits, and all kinds of vegetables." [162] This association was reorganized as the Manzanar Fruit & Canning Company in April 1919, affording it the right to "acquire, use, sell, or otherwise dispose of letters patent of the United States of America, or any foreign country, and any patent rights, licenses and privileges, inventions, improvements, processes, trade-marks, and trade names, labels and designs relating to or useful in connection with any business of the Corporation." [163] The focus of social life for the new community of Manzanar centered at the community hall. Farm bureau meetings — often attended by residents of Independence — followed by potluck suppers and dancing to live music provided by local musicians were held at the hall. The building was also the scene of weddings, funerals, anniversaries, Christmas celebrations, Ladies Aid Society meetings, and Sunday School and church services led at first by the Methodist Episcopal Mission and later by the Manzanar Methodist Episcopal Church which was formally established in June 1921. In addition, the hall housed the offices of the Owens Valley Improvement Company, a branch of the Inyo County library, and living quarters for farm and company personnel. After the establishment of extensive orchards at Manzanar, part of the building was converted for use as a packing house. During the mid-1920s a roller skating rink was constructed in the building. [164]

Social activities at Manzanar included summer picnics held in a grove south of town. Other recreational pursuits of Manzanar residents included camping in George Creek Canyon and along Shepherd Creek. The town fielded a baseball team that played teams from neighboring towns in Owens Valley. Fishing in nearby streams flowing from the mountains and hunting for wild geese, ducks, doves, pheasants, quail, rabbits, and deer were favorite pastimes for many men and boys. An annual fall farm festival was sponsored by the Farm Bureau. [165]

In 1912 the Manzanar School District was established, and on July 19 the Owens Valley Improvement Company conveyed a lot in the townsite to the district for construction of a school. A two-room school was built, with one teacher in the elementary school and another added later. High school students were bussed to Independence. By 1916, 29 pupils were enrolled at the Manzanar school, and by the early 1920s enrollment was in excess of 50 students as the population of Manzanar reached its peak and several students were gained following closure of the George Creek school. [166]

The Fourteenth Census taken in 1920 showed a total Inyo County population of 7,031 residents and a population of the Manzanar and Owenyo townships, which included George Creek, of 203. Of the 57 households at Manzanar that were surveyed, 42 lived on their own property and 15 were renters or operators for absentee owners. Nine Indians were living on 30 acres that had been set aside as U. S. Government land, while the rest of the population was white, with predominately northern European origins. Most residents, with the exception of the two teachers and the town's only merchant, R. J. Bandhauer, gave farming as their occupation. [167]

In 1924 the City of Los Angeles, having determined the need to increase its delivery of water to the city from Owens Valley, began taking options on the agricultural lands at Manzanar held by individual farmers and the Owens Valley Improvement Company in order to secure stream and groundwater rights. By this time the Manzanar development included Subdivisions Nos. 1, 2, and 3 plus the townsite for a total of approximately 3,000 acres. Property owners at Manzanar had lived with the possibility of this action for months, and reactions to it ranged from relief and eagerness to sell to anger and a feeling that they had been betrayed by both Los Angeles and their neighbors. [168]

Contrary to the glowing promises outlined by the Owens Valley Improvement Company, the Manzanar community had not prospered as expected. While the quality of Manzanar fruit was well-known throughout California, and the quantity in good years exceeded expectations, late frosts and untimely strong winds prevented the farmers from realizing consistent profits over the years. In addition, the problem of markets persisted as freight costs increased and competition from farmers in the Imperial and San Joaquin valleys resulted in lower profits for Manzanar fruit growers. Thus, while many of the farmers at Manzanar were eager to sell to Los Angeles and some even joined together to ask Los Angeles to accept their own terms of sale, others held out as long as possible before selling. Many residents later argued that the city had engaged in "checkerboard" buying and had pitted neighbor against neighbor, leaving a legacy of bitterness that lingered for years. According to most oral and written reminiscences by former Manzanar residents, those who finally left the area under whatever circumstances felt profoundly uprooted from a close-knit community. [169]

Several articles in the Inyo Independent during 1924 describe the purchase of Manzanar lands by the City of Los Angeles and the impact of the purchases on the Manzanar community. In March 1924, for instance, an article noted:

Word was received the first of the week that the options offered to Los Angeles by a combination of Manzanar and Georges Creek interests were not accepted by the City It is presumed that the value fixed for the water was more than the City desired to pay. While some of the ranch owners in the section mentioned were undoubtedly disappointed, yet other property owners who went into the deal, so we have been told, to conserve their interests, were not displeased with the outcome of the negotiations.

Later that year another article stated:

It would seem too bad for all the beautiful apple and other fruit orchards of Manzanar to be lost for lack of water; but no passing traveler is justified in saying what should be done or what should not. Try farming first, then try marketing what you raised; if you are not an experienced farmer and excellent hard worker it is not necessary to consider the market problem. After you have tried the farming game in a country where water is none too plentiful your eyes may be equipped with the same spectacles the rancher looks through.

In August 1924 another notice in the newspaper stated that the Rotharmel, R. A. Wilder, and R. J. Bandhauer families, all Manzanar residents, had "gone to Southern California to look for home locations." [170]

City of Los Angeles land purchases at Manzanar began in August 1924. The sale of the Owens Valley Improvement Company's property the following month placed at least half the Manzanar area under the control of the city. It is likely that this early sale was a reflection of the opportunity Chaffey and his company saw and seized to reach a settlement with Los Angeles for both the contested Cottonwood Creek water rights and sale of the Owens Valley Improvement Company lands as it was becoming clear that the years of the Manzanar community were approaching an end given the city's intention to purchase all of the privately-owned ranches in the valley. By 1927 Subdivisions Nos. 1, 2, and 3, and the Manzanar Townsite, a total of 3,000 acres, were entirely owned by the city. Of those who sold out and left Manzanar, some moved to emerging agricultural communities in Whittier and Chino in southern California or northern California. Others gave up farming altogether and settled in Lone Pine or Independence, often to go to work for the Department of Water and Power. Several of the former landowners remained, leasing their properties back from the city and continuing their farming operations as before. [171]

By 1926-27 the City of Angeles had become owner and absentee landlord of most of the land at Manzanar. Cognizant of the fact that it was responsible for managing the lands and maintaining harmonious relations on its new properties, city leaders launched an effort to reshape the area in line with its goals. Los Angeles wanted to protect the watershed that drained into its aqueduct, and thus it supported some types of agricultural activity as it realized that it could not merely quarantine Owens Valley The city wanted to ensure the efficient handling of the available supply of water in the valley, a goal that included the judicious use of water for agriculture with its potential for long-term groundwater storage, and it wanted to repair its image with the valley residents. The value of the agricultural enterprise at Manzanar could not be discounted as a means of recouping some of the costs of the land purchases. Thus, the city continued to farm portions of its newly-acquired property at Manzanar and to operate the packing house in the town's community hall. [172] The Los Angeles Times Farm and Orchard Magazine reported on the city's agricultural activities on June 13, 1926:

The case of the city's Manzanar tract purchase is interesting as showing what Los Angeles has been called upon to do in maintaining improved lands pending leasing arrangements. Here, out of 3000 acres acquired with water rights, around 1200 acres had at one time or another been developed, a considerable portion to orchards. Of the developed area a great deal had, in an acute water shortage just prior to the city's purchase in August, 1924, sadly deteriorated. It was squarely up to the city to step in and farm the tract for awhile.

The Manzanar tract had been about half sold out to individual owners, the other half being farnfed [sic] in part by the Owens Valley Improvement Company, which had subdivided it, when the city stepped in. Victor M. Christopher, who had been managing the company's farming operations, was employed by the city to look after the maintenance and leasing of the whole tract. He started in by giving the orchards a severe pruning followed by good irrigations. He had to yank out eighty acres of pears on one place because of blight. Some owners, too, had neglected their orchards so there was no saving them. Three hundred acres of fruit, however, have been well cared for, pruned, sprayed and irrigated, and of this a third has been leased. Last year Mr. Christopher sold a fair apple crop from city-owned orchards.

Some of the alfalfa fields of the tract were in a deplorable condition when the city took them over. This spring work is going ahead on improved water distributing lines designed to make possible a rapid extension of the alfalfa acreage. The city itself is now farming about 200 acres each of alfalfa and orchards and good crops are in sight. Los Angeles expects to be in the market again this year with premium hay and big red apples and the combined crops grown by the city and its tenants at Manzanar are sure to bring quite a figure. [173]

The farming operations conducted at Manzanar by the City of Los Angeles were described at length in another article in the Los Angeles Times Farm and Orchard Magazine on November 30, 1927. The article noted that "Growing apples unexcelled in quality even by the best produced in Northern California, Oregon or the Ozark Mountain region and distributing them under its own brand to all parts of the Southwest is one of the little-known features of the City of Los Angeles's agricultural and horticultural operations in the Owens Valley." The city's fruit-raising activities in the valley were "confined principally to Manzanar. There were approximately 300 acres of orchard, the "major portion of which has not yet attained a full-production stage." Two-thirds of this acreage was directly cared for by the city itself under the supervision of Farm Superintendent Victor N. Christopher," the remainder being leased. According to the article,

the tenants get the full benefit of the farm superintendent's experience and ability and this has proved of substantial value to them, especially in the preparation of the fruit for market and the manner of disposal. The unusual distance from the nearest center brings up difficult problems of packing, storage, freighting and sales commissions. The group system solved these most easily, efficiently and profitably. A Los Angeles company [Klein Simpson Fruit Company] handled last year's entire output satisfactorily.

The fruit crop at Manzanar in 1926 amounted to 55 carloads, including six of peaches, 12 of Bartlett pears, and 37 of apples. The latter were mainly winesaps with some delicious and Arkansas blacks. The city's crop made 18,650 boxes and that of the tenants 7,350.

The apple harvest at Manzanar "generally was so abundant," according to the article, that there was "no disposition on the part of buyers to stock up." Consequently the maximum figure of 75 cents per box "was offered for large size, extra fancy, delivered at the city's Manzanar packing-house, the buyer to do the grading and packing and furnish all materials." Considering all grades and sizes, this meant "only a net average of 50 cents per box, a sum that "seemed ridiculously low in view of the fact that Owens Valley apples seem to remain in tip-top shape after those from some other sections go into a state of decay." Thus, arrangements had been made "at once for the city to pack and store its stock instead of sacrificing." Thus, the entire crop had not been sold until August 1927, eleven months after having been placed in storage.

Christopher, a horticulturist, had protected the farm tenants by bargaining with the fruit concern to handle their output on consignment, the company advancing $1 per box to cover picking, packing, and freight costs. A Los Angeles cold storage plant held the apples at the season rate of 25 cents per box up to June 15, 1927, storage payable at the time of sale. The packing season at Manzanar started about September 20, 1926, and lasted five to six weeks. More than 20 persons were employed for the packing.

In round numbers, Los Angeles took in $40,000 for its Manzanar fruits, while its expenses were $30,000, leaving a profit of $10,000. Other farm profits brought the profits from the Manzanar district to $14,134.47, excluding taxes and interest. Twenty tons of hay was sold "in the stack for $12 per ton and 235 tons, worth the same price, [were] furnished for consumption on the city's construction works at the Haiwee generating plant, the Tinemaha dam and elsewhere along the Aqueduct." Fruit was also supplied to "various city camps in season.

Production costs after delivery to the packing house amounted to $1 per box. This figure included 20 cents for a box, 6 cents for a label and wraps, 20 cents for grading and packing, 6 cents for trucking 13 miles to Lone Pine, 19 cents for railroad freight to Los Angeles, 26 cents for cold storage, 2 cents for equipment, and 1 cent for miscellaneous items.

Late spring frosts in 1927 destroyed much of the Manzanar and Owens Valley fruit crop, thus making "apparent its uncertainty as a fruit country." This uncertainty, according to the article, would "in all probability lead to the discontinuance of orchard planting and use of the lands along surer and constantly remunerative channels." Like the rest of the valley, Manzanar "with its prodigiously fertile soil," had "plenty of other and reliable resources, actual and potential, the former including alfalfa, corn, potatoes, poultry, honey and garden truck." At present the city was cutting "the summer's last stand of hay," using blacks and Indians to do the work. New farming enterprises in the Manzanar vicinity included onions, chicken ranches, and honey production.

Before Los Angeles had purchased its Manzanar landholdings more than 1,200 acres had been farmed in the area. This acreage had been reduced to 1,000, because the water supply was inadequate. During years of normal or more than normal snowfall, when water for irrigation was plentiful, Los Angeles planned to enlarge the acreage farmed. The Manzanar lands were watered from Shepherd Creek "through a ditch ten years old, yet as sound as the day it was completed." The mile-long waterway, having a capacity of at least 100 inches, was built of granite boulders set in cement. The cost of maintaining the waterway was "practically nil and it will stand for decades with little repairing to be done."

Having taken over the Manzanar "lands to obtain the water and being engaged in direct farming merely pending other and better arrangements," Los Angeles, according to the article, now desired "to retire from that sphere and lease all its Manzanar holdings to individuals." Thus, opportunities existed for ranchers "financially able to swing such propositions and seeking new fields of conquest." [174]

Although Los Angeles continued to conduct agricultural operations on some of its lands at Manzanar, significant portions of the once highly-acclaimed irrigation system were allowed to deteriorate. One writer who decried the "rape" of Owens Valley by the City of Los Angeles wrote a series of articles in the Sacramento Union during March 28 to April 2, 1927. The author observed that Owens Valley was a "Pitiful Story of an Agricultural Paradise, Created by California Pioneers, Condemned to Desert Waste by Water Looters."

Regarding the demise of many of the orchards at Manzanar, he noted:

Manzanar was once famous for its apples. The orchardists of Manzanar won first prizes at the State Fair in Sacramento and at the Watsonville apple show. A commodious packing plant was erected. The community was prosperous. It was growing rapidly. The village school had two teachers and there was talk of a new school building.

The Los Angeles water and power board came and bought every orchard and ranch that its agents could trick the owners into selling. The city immediately diverted the water from the ditches into the aqueduct. It dug wells and installed pumps to exhaust the underground water supply.

Today Manzanar is a ghastly place. The orchards have died. The city has sent tractors to pull up the apple trees. This should be a week of pink and white blossoms in "Apple Land," instead there is only desolation. Vigorous trees just coming into full bearing are prostrate in one field; across the road the blazing trail of the fire brand is visible. [175]

The Manzanar community declined after the mid-1920s. Many of the houses vacated by farmers who sold their property to Los Angeles were rented to Department of Water and Power employees, farm tenants, and other workers from Independence. Some farm buildings were torn down, their materials being salvaged by the Department of Water and Power for other use. Some structures were purchased and moved to Independence and Lone Pine, while some simply deteriorated or were destroyed by windstorms or fire. [176]

The decline of the Manzanar community resulted in closure of its post office on December 31, 1929. In 1932 the Manzanar Water Corporation was dissolved. Two years later, Los Angeles determined to stop irrigation entirely and increase groundwater pumping in the Manzanar area. Thus, the remaining orchards and farmlands were abandoned and allowed to dry up. Two families who remained at Manzanar in 1934 moved to Lone Pine and Independence, and in 1935, Clarence Butterfield, poultry farmer and last remaining resident, was asked by the Department of Water and Power to move. The following year the Manzanar school closed, and the Manzanar school district joined with Independence to form a unified district. On October 6, 1941, two months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Inyo County Board of Supervisors passed a resolution at the request of the City of Los Angeles that "all streets, alleys, lanes, etc. in the Town of Manzanar be abandoned. [177]

In March 1942, at the time the Army leased 6,020 acres from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power for construction of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, two ranchers were leasing portions of the affected acreage. Archie Dean was leasing "dry brush grazing land" north and northeast from the former Manzanar townsite and the Manzanar airport, which had been surveyed in July 1941 and subsequently constructed by the United States Government, under a three-year lease at an annual fee of $110. His original lease had been modified to cover land which was included in the lease to Inyo County for the Manzanar "airport site. Peter Mairs had a lease which expired on March I, 1942, covering land irrigated from George Creek and other dry grazing land located on the east side of the highway and below the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Mairs paid an annual fee of $1,890 for the land on which he grazed cattle. [178]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

manz/hrs/hrs6c.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2002