|

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter Three:

ARCHITECTURAL RESOURCES OF THE MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, CA. 1880-1950 (continued)

AUBURN AVENUE DEVELOPMENT

Beginning in 1880, the heirs of John Lynch began to divide and sell his large property holdings along Auburn Avenue between Jackson and Howland (now Howell). Some residential development was evident, but it was located primarily north of Auburn Avenue. 521 Auburn Avenue, built on property formerly part of the John Lynch estate between 1882 and 1888, was an early residence on Auburn Avenue east of Boulevard. It is the only extant residence built prior to 1890 within the Site. Other residences appeared in rapid succession beginning in the 1890s. By 1899, most lots along Auburn between Jackson and Howell were developed, although denser residential development remained west. The residences within the Site varied in size and type, but most were two-story wood dwellings with one-story rear extensions. The north side of Auburn Avenue between Hogue and Howell has shallow, narrow lots occupied by seven two-story dwellings. Access to the rear of the north side lots was off Old Wheat Street. The south side, however, developed less rigorously. This resulted in larger lots and fewer houses, with varied, and deeper, setbacks from the street. Access to the rear of the southside lots was by driveways off of Auburn Avenue.

Small-scale commercial development accompanied residential growth. Several corner stores and restaurants served Auburn Avenue residents. One was located on the northwest corner of Boulevard and Auburn. Another corner grocery operated by a succession of whites was located across from the Birth Home in a building constructed in 1909 on the northwest corner of Hogue and Auburn (502 Auburn). During the 1920s, a small, one-room building (521-1/2 Auburn Avenue) was intermittently operated as a soda fountain and cafe, in front of 521 Auburn Avenue. Another small building, located at 57 Howell, housed a restaurant during the 1930s. The Jenkins family, owners of the parcel of land in the triangle bounded by Auburn, Old Wheat and Howell streets, built two store buildings (554 and 556 Auburn) adjacent to their residence at 550 Auburn. The buildings, now demolished, were leased to a series of white grocers and butchers. The original residence was divided into apartments ca. 1900, and the Jenkins family owned the properties until 1963.

Two churches, Ebenezer Baptist and Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, are located within the Site. In 1912, the Catholic church constructed a three-story stone church and school building. Fire Station Number Six occupied the southeast corner of Auburn and Boulevard and served the surrounding residential community, consisting primarily of wood structures, beginning in 1894. [92]

In 1905, the Empire State Investment Company developed the northeast corner of Auburn and Boulevard. Empire bought the unimproved property from Adolphus Tittlebaum for $3650 and built nine duplex dwellings that occupied half of the block between Boulevard and Hogue. One of the lots was sold in November 1905 for 1800 as a rental property. These duplex shotgun dwellings were a sharp break from the existing houses on Auburn but were typical of dwellings to the north. They also represented the first low-cost rental housing built in the Site. [93]

Prior to 1900, Auburn Avenue east of Jackson Street developed as a predominantly white, middle-class residential district. Single-family, one- and two-story houses constructed in the 1890s lined principal streets. Some multiple-family dwellings were present, but the majority were large, modestly decorated houses. Many had stables and wood and coal sheds in the rear. When Empire constructed the nine duplexes, it foreshadowed a change, suggesting that multiple-family housing was in demand in the area. Many multiple-family units were constructed on alleys or subdivided portions of original lots. The 1906 race riot, fought in the streets and on the streetcars less than a mile away, also influenced the course of development on Auburn Avenue.

Between 1909 and 1910, most white-occupied houses on the Birth-Home Block were sold or leased to blacks. By 1920, the Auburn Avenue neighborhood was overwhelmingly black. Auburn Avenue comprised the southern boundary of a developing black middle-class neighborhood which adjoined Morris Brown College, established in 1881 and located at Boulevard and Irwin Street. [94] But not all neighborhood residents were middle class. Many were service workers or manual laborers. Several duplex residences were constructed between 1911 and 1928 behind the larger homes on Auburn Avenue and on alleys accessed from Edgewood Avenue to the south. The larger houses on Auburn were occupied by black professionals and business people. The multiple-family dwellings and the small, two- and three-room houses sheltered working-class families. [95]

Auburn Avenue west of Jackson, within the Preservation District but outside the Site, developed as a black business enclave following the race riot of 1906, when many black businesses left downtown. Businesses ranged from small retail concerns like groceries and barber shops to banks and insurance companies serving the Atlanta black community. Black entrepreneurs developed a number of commercial buildings in this area, including the three-story Rucker Building of 1904 (158-160 Auburn Avenue) and the four-story Herndon Building of 1926 (231-245 Auburn Avenue).

The six-story Odd Fellows Building, constructed in 1912, and its adjacent 1913 auditorium building (228-250 Auburn Avenue) were important centers of black business and social life. Auburn Avenue remained a center of black business activity into the 1950s. [96]

Although the black business district west of Jackson continued to prosper between 1920 and 1950, Auburn Avenue and surrounding residential streets failed to attract or keep community residents engaged in professional occupations. By 1930, few middle class residents remained on Auburn Avenue. This decline manifested itself in various ways. Several multiple-family dwellings were constructed on the Birth-Home Block and adjacent streets. Apartment houses at 509 Auburn (later demolished) and 506 Auburn were built in 1925 and 1933, respectively. Another quadraplex at 54 Howell Street was constructed in 1931 and subdivided an already crowded house lot. During the 1930s, Auburn Avenue witnessed the subdivision of single-family dwellings, the deterioration of its housing, and increased tenancy. By 1940, the U.S. Census reported that two-thirds of the dwelling units in the Site were in disrepair and 77 percent lacked a private bath. [97]

By 1940, few people living on Auburn could afford to own their homes, and the area had become increasingly transient. Most tenants remained less than five years. [98] Most residents had little money for house maintenance, and by the late 1930s Martin Luther King, Sr., described the Birth-Home Block neighborhood as "running down." He moved his family to a house several blocks away on Boulevard in 1941. [99] Between 1930 and 1950, Auburn Avenue increasingly became an impoverished black working-class district. In the 1960s, when housing options for blacks in other parts of the city expanded again, the Auburn Avenue area began to decline more rapidly. [100]

The historic streetscape features of Auburn Avenue are essential in establishing the physical context in which King was born, where he lived, and where he worked. The major spatial relationships that define the streetscape within the Birth-Home block, have remained relatively constant since its development in the late nineteenth century. A fairly consistent right-of-way on Auburn has been maintained, measuring fifty-eight to sixty feet wide within which a forty-foot wide (curb to curb) two-way traffic lane is centered.

According to City Council records, brick sidewalks were laid with granite curbing along both sides of Auburn Avenue through the Birth-Home block as early as the I 890s. This predates the paving of the street in this area by at least a decade. Boulevard, where the street car line turned north off Auburn Avenue, often marks a transition point in the city services, and records show that in 1913 residents east of Boulevard petitioned to have Auburn paved from Boulevard to Randolph. Although the date of the first paving of this area of Auburn Avenue is not clear from the records, City Council minutes do show that in 1922 the "old pavement" was "condemned" from Boulevard to Randolph Street and was to be repaved with concrete. At this time, the existing brick sidewalks along Auburn Avenue were also to be replaced with concrete walks with the granite curbs retained. [101] Remnants of the original brick sidewalks survive at the northwest corner of Howell Street and Auburn Avenue and along the north side of Auburn Avenue, in the triangle east of Howell Street (photograph 10). An original stretch of the exposed river-stone aggregate sidewalk that was poured in the 1920s exists along the north side of Auburn Avenue between Hogue Street and Howell Street.

|

| Photograph 10: Brick sidewalk, north side of Auburn Avenue east of Howell Street. |

In 1924 an ordinance calling for the paving of Howell Street NE was passed and specified to be "Extra Vibrolithic concrete, six inches thick." City Council records make no mention of the street surfaces along Old Wheat and Hogue, but by the 1937 Cadastral Survey both of these streets were paved with concrete, with granite curbs. Old Wheat Street never had sidewalks, and the earlier brick sidewalks were to remain along Howell Street, although Hogue Street sidewalks were concrete by the 1937 Cadastral survey. [102] These original concrete sidewalks still exist along Hogue Street between Auburn Avenue and Old Wheat Street.

Other streetscape features that have been described in oral histories to have existed within the Site during the 1929-1941 period include street trees (two of the three noted in 1949 aerial photography survive at the northwest corner of Auburn Avenue at the intersection with Howell Street), street lighting at the top of wooden poles and described by former residents as "coolie hat" lamps (no extant examples), and fire hydrants on the northwest corners of Auburn and Boulevard, Hogue and Howell (1970s models have replaced the 1930s hydrants in the same location). [103]

Residential Architectural Resources

The architectural resources of the Auburn Avenue portion of the Site (which includes adjoining portions of Boulevard, Hogue, and Howell streets) are predominantly residential. The following discussion of the residential buildings of Auburn Avenue is organized chronologically. Site resources will be related to broader currents in American architecture from 1880 to 1950.

The two primary analytical categories for discussing American houses are styles and types. The concept of architectural style is a notoriously slippery one, embracing both the decorative treatment and the overall configuration or form of a house. Ornament is usually the clearest indicator of style, with form a secondary aspect. For example, the Italianate style is defined in terms of its decoration (an elaborate cornice, heavy brackets, and molded window hoods), proportions (tall, narrow windows and doors), and typical forms (low-pitched roof, overhanging eaves, and towers). Stylistic analysis emphasizes successive style periods, bounded by approximate beginning and ending dates. The concept of style is most useful in discussing the unique designs of professional architects for affluent clients, representing perhaps 5 percent of American buildings. These are referred to as "high style" examples. The remaining 95 percent of buildings are usually classified as vernacular architecture.

House types, rather than styles, are the usual analytical categories applied to vernacular architecture. House types are identified on the basis of ground plan (e.g., square, rectangle, L-shape), number of stories, and roof configuration (e.g., hip, gable). An example of a house type is the gable front and wing house, or L-shaped house, defined by its L-shaped ground plan and cross-gable roof. The amount of ornament found on vernacular houses varies considerably. Examples of vernacular building types that incorporate ornament are widely viewed as borrowing these elements from high style architecture. Thus, a vernacular L-shaped house may have a cornice and brackets associated with the Italianate style.

Many terms describing house styles and types have gained nearly universal currency and will be used in this study. Auburn Avenue residences combine traditional massing (i.e., rectangular, L-shaped, square, or complex) common to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and elements of popular national architectural styles. At times, a house embodies both the massing and the decoration of a period and style. But most commonly, the houses along the Birth-Home Block are vernacular houses with various levels of stylistic decoration. Some Site resources, such as the double shotgun cottages, are best analyzed in terms of house type since their decorative elements are not rigidly defined by a dominant style. Other resources, such as the two-story houses on the Birth-Home Block, represent traditional Queen Anne massing and decorative elements. Most Birth-Home Block resources are not the works of an individual architect, and thus, they are typical of residential architecture in early twentieth century American cities.

Single-Family Residences

ITALIANATE—The large single-family house at 521 Auburn, built in the 1880s and subsequently divided into apartments, is a Georgian cottage type (square massed) with Italianate stylistic details. The oldest extant Site building, the house was constructed on a large lot at a time when much of the surrounding land was undeveloped.

The Italianate style was popular for residences from approximately 1840 to 1880, with its greatest acceptance coming after 1860. The style originated in England in the early nineteenth century as part of the enthusiasm for the Picturesque. Devotees of the Picturesque rejected formality and classical symmetry and sought inspiration from exotic sources. Informal, asymmetrical Italian farmhouses were the inspiration for the Italianate and Italian villa styles in England and America. The architectural pattern books of Andrew Jackson Downing, first published in the 1840s and reprinted into the 1 880s, helped popularize the Italianate style in America. The Italianate style combines both symmetrical and asymmetrical L- or T-shape plans and a tall tower. Builders soon applied Italianate details to traditional rectangular American house forms. [104]

Italianate houses typically had low-pitched roofs with broad overhanging eaves; elaborately molded cornices with heavy, often paired, brackets; tall, narrow windows, commonly with round or segmental arch heads; and frequently elaborate window crowns. Paired windows were common, and porches were almost always present, sometimes with ornate carved and turned balusters and posts. Examples of the style are not abundant in the South because the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the depression of the 1870s limited building activity in the region during the style's period of greatest popularity. [105]

The house at 521 Auburn Avenue exhibits Italianate decorative elements applied to a traditional vernacular house type (photograph 11). The Georgian cottage type has a long history in the South and is characterized by a square or nearly square plan, a central hall with two rooms on either side, exterior symmetry, and a height not exceeding one and one-half stories. [106] 521 Auburn Avenue does not display the asymmetry and two- to three-story height often associated with the Italianate style. Italianate features on the house include a molded cornice with heavy brackets, projecting bays at the sides with similar cornices and brackets, and hooded windows. The use of Italianate features on a house built when Auburn Avenue was semi-rural in character recalls the ultimate origins of the style in the farmhouses of the Italian countryside.

|

| Photograph 11: 521 Auburn and sidewalk store building |

521 Auburn is set back farther from the street on a larger lot than its later neighbors. The front yard is dominated by two oak trees and is bordered by a hedge and a fence. The historic concrete front walk has distinct detailing that includes a diagonal scoring pattern and rolled curb-edge detail along the length of the walk. At the front northeast corner of the lot, behind the sidewalk, is a plain, rectangular frame building, constructed about 1920, that was operated by blacks as a soda fountain and cafe in the 1930s and may have had other commercial uses. [107] As the only extant store building within the residential portion of the Site, this structure is an important reminder of the diverse character of Auburn Avenue during the period of Dr. King's residence.

QUEEN ANNE—As Atlanta outgrew its pedestrian limits in the 1890s, large, two-story houses were constructed on Auburn Avenue. Most of these single-family houses, including the Birth Home and its neighbors, incorporated features associated with the Queen Anne style (photograph 12). Queen Anne is a stylistic term that incorporates decorative elements and house typology. A defining characteristic of the style is complex massing and multiple roof forms. Other Site houses from the 1890s are examples of vernacular gable front and gable-front-and-wing houses (gabled-ell) with Queen Anne style decorative elements.

|

| Photograph 12: 522 Auburn Avenue |

The Queen Anne style was popular nationally from approximately 1880 to 1910. The style originated in the 1860s and 1870s with the English designs of Richard Norman Shaw, W. Eden Nesfield, and others. These architects revived late medieval and early Renaissance forms and materials, such as half-timbering, casement windows, elaborate brick chimney pots, gable-end barge boards, and ceramic tile cladding of exterior walls, and used them in novel combinations. Henry Hobson Richardson's 1874 Watts Sherman House in Newport, Rhode Island, generally considered the first American example of the Queen Anne style, incorporated many of these features. The influential designs of Shaw and Richardson were expansive and manorial, but the vast majority of American Queen Anne houses were modest wooden structures built for the middle class. [108]

American Queen Anne houses achieved dramatic visual effects through the use of contrasting textures, colors, shapes, and materials. Characteristics are irregular, asymmetrical plans; hipped roofs with lower cross gables; projecting features such as bays, turrets, and gable overhangs; elaborate wooden millwork; and the use of textured decorative shingles on exterior walls. Porches were nearly universal and often wrapped around one or both sides of a house. Queen Anne house plans were usually asymmetrical, with an off-center entry and an informal arrangement of rooms. Builders' pattern books helped popularize the style nationally, and railroad transportation made available the mass-produced wooden ornament typical of the style. [109]

The Birth Home at 501 Auburn, built circa 1894 for a white family named Holbrook and restored by the NPS, is a good example of a two-story middle-class house incorporating Queen Anne elements (see photograph 5, page 26). In plan, the house is an elongated rectangle with shallow projections on all four sides. The principal roof is hipped, with gable roofs over the projections. The asymmetrical facade is dominated by a front-facing gable and a one-story, full-width porch that wraps partly around the west side of the structure. The porch has turned posts, scrollwork brackets, and a simple openwork balustrade. Paired double-hung windows with louvered shutters are present at the first and second floors under the gable end, which contains a rectangular vent and is bordered below by a pent roof. To the right of the entrance is a circular window. At the second floor, above the entrance, is a small porch with a shed roof. The porch was originally accessed by a door, which was converted to a double-hung window before 1929. The house has weatherboard siding, with decorative shingles in the gable ends. [110]

The Birth Home is set on a typically long and narrow urban lot forty feet wide and 195 feet deep. The house is set back thirty-eight feet from the front lot line and is reached by a walkway of octagonal payers. A concrete block retaining wall, approximately two feet high, separates the elevated front yard from the sidewalk. A privet hedge, approximately three feet high, is planted on top of the wall and encloses the front yard. The east side yard of the Birth Home shares a driveway with 503 Auburn Avenue. A shed, which no longer exists, sat on the east side of the back yard and was converted to a garage by the King family when they bought a car. Other back yard features no longer extant include a vegetable garden on the east, [111] another small shed behind the garden, which served as a coal shed, and wire clotheslines that ran from the house to the shed, supported in the middle with sticks, and from the west corner of the house to the fence. The entire back yard was enclosed by an unpainted board fence, with irregularly spaced boards. The west side yard was extremely narrow. Only a remnant of the low wall, which filled the narrow space between the Birth Home and 497 Auburn Avenue, exists.

The Birth Home's main entrance opens on a small foyer that extends into a sidehall running the length of the house. On the east side of the hall (to the left as one enters) from front to back are a parlor, study, dining room, and kitchen. On the west side of the hall are stairs to the second floor and the basement and a bedroom and bath at the back. The second floor hall extends the length of the building, with three bedrooms on the east and one on the west.

BIRTH-HOME BLOCK—Most houses on the Birth-Home Block built in the 1890s exhibit Queen Anne features. Like the Birth Home, the two-story Harper house at 535 Auburn Avenue has a hipped principal roof and a front-facing gable projection. The gable end projects over a three-sided cutaway bay, with decorative sawn brackets in the overhangs. A porch with turned posts and a stick frieze runs across the front of the house. Other Queen Anne variations represented at the Site include two front-facing gables (518 Auburn Avenue), jigsawn wall panels (503 Auburn Avenue), and decorative trusswork in the gable end (514 Auburn Avenue). These houses demonstrate the visual variety achieved through combinations of mass-produced ornament in this period.

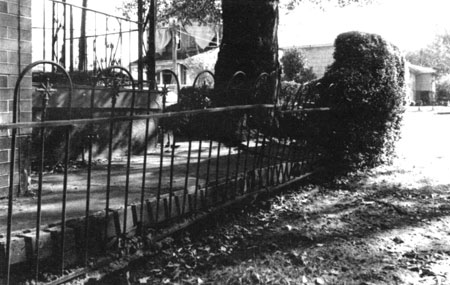

Distinctive landscape features associated with the Queen Anne houses include concrete front walks (518 Auburn Avenue), rear and side-yard walls of mixed rubble materials (510, 514, and 522 Auburn Avenue) and side-yard retaining walls to hold the grade of the front yard even with Auburn Avenue (526 and 530 Auburn Avenue). Granite steps with a thin marble cheek-wall treatment, dating from before 1915, are extant at the sidewalk of 503 Auburn Avenue. An early ornamental iron fence remains around the front and side yards of 530 Auburn Avenue (photograph 13). One of the last rear yard outbuildings/garages within Site survives at 497 Auburn Avenue.

|

| Photograph 13: Iron fence at 530 Auburn Avenue. |

Several Site houses, built between 1890 and 1910, are vernacular types with limited decoration. These include a gable-front-and-wing house at 546 Auburn Avenue, a T-plan, side-gabled house with a hip roof rear portion at 540 Auburn Avenue (photograph 14), and gable-front houses at 24 and 28 Howell Street and 53 Hogue (photograph 15). Decoration on these houses is limited to the porches that exhibit turned or chamfered posts, brackets, and balustrades.

|

| Photograph 14: 540 Auburn Avenue. |

|

| Photograph 15: 53 Hogue Street. |

After 1900, few large single-family homes were built in the Auburn Avenue neighborhood. Middle-class blacks moved into existing single-family houses, and new construction for working-class blacks was limited to duplexes or small apartment buildings. Many duplexes were double shotgun houses, a common southern vernacular type. Twelve double shotgun houses are located within the Site.

Multiple-Family Residences

A distinctive multiple-family house type within the Site is the double shotgun house. Appearing in New Orleans as early as the 1830s, the shotgun house was diffused throughout the South, at first along river trade routes and later in other areas. The type's greatest popularity came between 1880 and 1920, when it was a common choice for mill housing and for speculative developments marketed to working-class whites and blacks. The origins of the type have been debated by historians, some of whom have argued that slaves brought the type from West Africa to Haiti and then to New Orleans. Others have suggested that it originated when the traditional hall and parlor plan was turned sideways to accommodate narrow urban lots. [112]

The defining characteristic of the shotgun type is a plan one room wide and two or three rooms deep. The name derives from this arrangement of rooms opening directly into one another. A shotgun blast fired through the front door supposedly would travel through the house and exit at the back without hitting a wall. The long, narrow configuration of the house made the type a good fit for narrow-frontage urban lots. Shotguns are one-story houses with a door and window on the front elevation and a hip or gable roof. Shotguns commonly exhibit engaged or attached front porches, typically gabled or shed. The chimneys are usually central. Many shotguns lack stylistic features, since they are utilitarian in nature, but some examples incorporate decorative millwork. The double shotgun house is a four-bay, duplex version consisting of two shotgun-plan flats under one roof, joined by a party wall. The porches, chimney placement, and entry location vary among double shotguns, which first appeared in New Orleans around 1850 and spread throughout the South. [113]

In 1905, the Empire State Investment Company purchased the western portion of the block bounded by Auburn Avenue, Boulevard, and Old Wheat Street and constructed nine double shotgun houses there (photograph 16). Built as speculative rental housing for whites, the double shotguns were all black-occupied by 1910. [114] As built, these double shotguns had hipped roofs, weatherboard siding, and hipped front porches for each unit. Ornament was limited to turned posts and sawn brackets on the porches. Many single and double shotgun houses are located within the Preservation District, an area bounded by Old Wheat Street, Boulevard, Irwin Street, and Randolph Street. The shotgun houses within the Site and the Preservation District vary in ornamentation, roof type, number of rooms, and type of porches, but they all served as inexpensive, multiple-family dwellings for working-class blacks.

|

| Photograph 16: Double shotgun houses at 472-474 and 476-478 Auburn Avenue. |

Landscape features historically associated with the double shotguns were swept (dirt) yards. No extant examples of this feature are found in the neighborhood. Paved and unpaved alleys and their associated infill structures were once common in the area; the alley and three double shotgun residences behind 493 Auburn Avenue are the only surviving examples within the Site.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a number of the single-family houses on Auburn were converted to apartments or rooming houses. Small apartment buildings were also constructed in this period. Three small apartment buildings, constructed between 1911 and 1933, are located at 491-493 Auburn Avenue, 506 Auburn Avenue, and 54 Howell Street. All are plain, two-story, rectangular structures with two-story porches, weatherboard siding, and hip or gable roofs (photograph 17). Built for working-class blacks, these buildings are utilitarian and largely unornamented. The flats in these buildings are generally small; those on the first floor have access directly from the porch, while central stair halls provide access to upper floors. These buildings probably offered shared bathrooms when built. The 1931 apartment building at 54 Howell Street has exposed rafters and triangular braces in the gable ends, features often associated with the Craftsman style, popular from approximately 1905 to 1930.

|

| Photograph 17: 54 Howell Street. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/malu/hrs/hrs3a.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002