|

Jefferson National Expansion

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER THREE:

The Veiled Prophet Fair

History of the Event

The annual Veiled Prophet Fair (VP Fair) is an event which contributes to the unique character of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. It is also one of the most controversial and unusual aspects of the memorial's recent history. Billed as the nation's largest Fourth of July celebration, with attendance figures in excess of 2.5 million people annually, [1] the VP Fair is held on the grounds of a national park, with most of the necessary costs and repairs paid for by the local Veiled Prophet Fair Foundation. Air shows, live music, nationally known celebrities, educational and family attractions, food, and fantastic evening fireworks displays attract visitors from across the country and around the world.

The VP Fair has its roots in the agricultural and mechanical fairs held in St. Louis beginning in 1856. These fairs had lost their momentum by March 20, 1878, when Charles Slayback, an influential grain broker, invited St. Louis businessmen to a meeting at the Lindell Hotel. At the meeting, Slayback proposed an annual event similar to the New Orleans Mardi Gras, hoping that such a festival would spark public interest and boost attendance at the October harvest fairs. [2]

To stimulate curiosity in the proposed event, Slayback's brother Alonzo drew upon a mythical character created by Irish poet Thomas Moore in 1817, the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan. Changing Moore's legend to suit the needs of promoting the fair, Alonzo Slayback's Veiled Prophet was no longer a "war-mongering trickster," but an entrepreneur who wanted to share his personal happiness with another part of the world. In Slayback's version of the legend, the Veiled Prophet traveled over the globe, finally stopping in St. Louis, which he made his adopted city. He believed the citizens of St. Louis to be much like the people of Khorassan, contented and hard-working. He informed city officials that he would return in one year to share his happiness with them, telling them that they must prepare for his arrival. [3]

Such a "hook" for the enticement of the public appealed to the businessmen, who formed a secretive, elite society called "The Mysterious Order of The Veiled Prophet."

Plans were made for an evening parade and a grand ball, the first of which were held on October 8, 1878. The event was enormously popular, with more than 50,000 people lining the parade route that first year. The Veiled Prophet parade and ball became annual events, as well as a traditional part of life in St. Louis. [4]

In the early 1980s, it seemed logical to expand the Veiled Prophet event beyond a parade, changing its scope from a city-wide celebration to one worthy of national attention. Robert R. Hermann, a St. Louis businessman and civic promoter, also wanted to elaborate on the July Fourth "Freedom Festival" riverfront fireworks show, traditionally sponsored by St. Louis' Famous-Barr Stores and KMOX-AM Radio. While very popular, the Freedom Festival offered little food or entertainment. [5]

Superintendent Jerry Schober recalled the beginning of JEFF's involvement with the fair, which began soon after his arrival in the park:

Within probably five weeks after I got aboard, the mayor of the town asked if he could come visit me. And it was set for nine o'clock, but by nine o'clock there was no sight of him. I finally found out that he thought my office was down under the Arch. And so he had actually waded through the mud [the grounds were torn up due to extensive landscaping at the time] to get there with these big open trenches. And when he came in we made a little small talk. And all of a sudden he said, "We want to put on one of the largest events in the United States." A guy by the name of Robert Hermann had been doing a lot of research on this in different places. They did not know exactly how they wanted it, but they wanted it in the largest open area next to the river. And of course that was the Arch grounds. . . I said, "Mr. Mayor, I think it is lucky you did not fall in one of those trenches coming over here. . . I don't see how we can do it. The landscaping won't be done . . . "

The only way I could put him off was by talking to him in his office. . . . The mayor was still rather insistent. So I said, "Well, Mr. Mayor, like I told you on the last visit, I certainly did not want to come here to start telling you no. So I offer you another suggestion rather then tell you no. As soon as you send me a letter saying that you will assume all the liability for such an event, if anybody is injured, hurt or anything else, that the City of St. Louis will take care of it, and if it satisfies our solicitor, I will certainly give you a permit for this big outing."

He said, "Well, I've never been asked anything like that."

"Well, that makes two of us because I have never been asked to put on an event like you are talking about either."

So we finally agreed that we wouldn't have it that year. And so it was the following year that we had it, which was still, I think, a year too soon. [6]

In 1981, Robert R. Hermann recruited 100 community leaders to organize the first Veiled Prophet Fair to be held on the Mississippi riverfront. The NPS issued a special use permit to the City of St. Louis, which, in turn, issued the permit to the VP Fair Foundation. The fair opened on Saturday, July 4, 1981, following the previous evening's VP Parade. Fifteen community and charitable organizations staffed food and beverage booths, and approximately 3,000 volunteers managed entertainment activities around JEFF's grounds. Nearly a million people attended the fair. The money that was raised was used to organize and stage the second fair in 1982. [7] Superintendent Schober recalled:

[The] Fourth of July celebration . . . ran sometimes for two days, three days, and eventually we even had some that were four-day affairs. But we did things totally different than I had done when I was working in Washington D.C., when I had the monuments and memorials. Here, I required the VP Fair and the City of St. Louis to accept the liability and also to accept property damage. They had to have insurance and I had to have proof of such insurance in my hands . . . ninety days before the fair started, or we would not have it. [8]

Over the next several years the fair continued to grow in size. In 1982 approximately 3 million people attended; by 1983 "America's Biggest Birthday Party," as it was being billed, was attracting nearly 4 million. It also received national attention with coverage from the NBC television network in 1984, and was the location for major television specials on ABC in 1987 and 1988. The Veiled Prophet Fair experienced a metamorphosis during the 1980s, from a rather rowdy celebration with a sometimes unruly crowd to a family-focused event with an emphasis on particular themes such as "Education" and "Parks USA." [9]

Minimizing the Damage

Due to the evolving nature of the fair, the early years were trial and error ones for park officials. As time went on they began to learn how best to manage such a major event. A primary area of concern for the NPS was the protection of the grounds and natural resources of the site. Strict limitations were developed over time that minimized the adverse effects of the early fairs, when the grounds and trees sustained heavy damage from the use of vehicles and equipment to set up and take down booths and stages, and the presence of large concentrations of people.

In order to use the JEFF grounds, the VP Fair Foundation applied to the NPS, through the City of St. Louis, for a special use permit. Typical provisions included the installation by the VP Fair Foundation of fences around all areas with shrubs and ground cover; the prohibition of motorized vehicles on the grounds between 9:00 AM and 10:00 PM, in the interest of safety; proof of adequate insurance coverage, with the NPS named as coinsured; and the agreement on the part of the foundation to replace all damaged trees and shrubs, as well as responsibility for re-sodding and reseeding of grassy areas. The NPS, through the superintendent, reserved full veto power over any activity deemed inappropriate. [10]

The administration of these regulations was largely successful. Although the memorial grounds were heavily impacted during particular years, such as 1982 and 1987, when the 3-day event was marked by almost continuous torrential rains, the VP Fair Foundation has usually honored its promise to repair the annual damage. Superintendent Schober lamented:

|

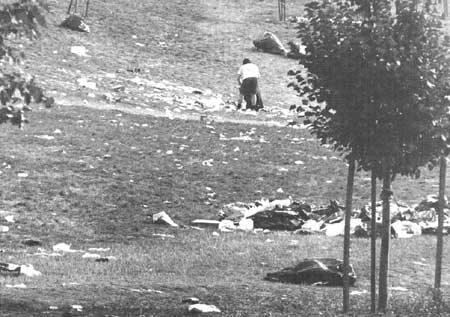

| Clean-up from the 1982 VP Fair. Courtesy John Weddle. |

[The] first year we started the repair of the grounds, but we thought it would be an insignificant amount. I never really asked how much it cost them. . . . We finally agreed on a contractor who laid the landscaping out. And then we found a landscape architect who we both respected, they paid for him, and he came out to assess what had to be repaired. . . I know one year [1982] it had to be a quarter of a million dollars worth of repairs. . . . We even had to redo the irrigation lines underneath. [11]

|

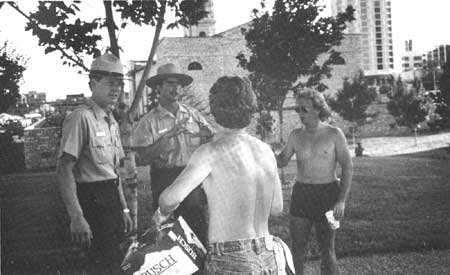

| Patrons of the 1982 VP Fair with liquor they brought onto the grounds. NPS photo. |

In addition to protecting the grounds and natural resources, visitor safety was a major concern, both for the VP Fair Foundation and the NPS. Some fairgoers opted to bring their own liquor with them onto the grounds rather than patronize the beer vendors onsite. Problems resulted from the excessive consumption of alcohol and shards of glass which littered the park where bottles had been carelessly discarded. In response to the problems caused by alcohol brought onto the grounds and smashed glass containers, the city passed an ordinance prohibiting both in 1985. [12] This law resulted in an elimination of some of the rowdy element in the crowds.

Vehicle use on the grounds during the fair was restricted, also out of concern for visitor safety. Motorized vehicles were always prohibited during peak hours of visitation, with the major exception of golf carts and emergency vehicles. The golf carts were used by fair "marshals," the volunteer workers, for transport from one area to another. But as the size of the crowds increased over the years, even the golf carts became potential safety hazards. In 1989 the NPS decided to prohibit their use at future fairs by any but Emergency Medical Services personnel. [13]

By 1990 experience and advance planning resulted in effective management of the VP Fair. Workable systems were in place to assure safe and smooth running operations. An average of 20,000 volunteers staffed the booths each year. [14] The NPS maintenance crew perfected the repair of the grounds to an almost scientific efficiency. [15]

Visitor Protection

A major concern for the NPS regarding the VP Fair was the additional costs incurred due to the need for increased law enforcement personnel. The large crowds of fairgoers made it necessary for the NPS to bring in special event teams from other park areas. This meant paying travel and overtime expenses above and beyond normal budgets. In 1982 the estimated cost to the NPS for these expenses was $50,000; by 1984, with the growth of the fair, costs had risen to $106,000. To meet this need, special appeals were initially made to the Emergency Law and Order Fund. [16] In 1985, however, the decision was made in the NPS Washington Office that such funds would no longer be available to cover the costs of the fair. After 1985 all necessary funds would have to be budgeted or provided for by the city or the VP Fair Foundation. [17] This decision led to the development of a stipulation in special use permits issued for the fair, requiring the payment of all the NPS' extra expenses. [18]

Costs formerly covered by federal money amounted to $90,000 in 1987, and to receive its permit the VP Fair Foundation was required by the NPS to pay in advance. [19] The foundation was also charged for all subsequent expenses beyond the original estimates. In 1988 this amounted to more than $25,000. Despite some difficulties in collecting these additional charges, in each instance the foundation eventually paid in full. "We felt that we had to have an increased number of rangers out there to protect the grounds, even though we had up to five hundred St. Louis city police," recalled Superintendent Schober.

|

| Law enforcement rangers at the VP Fair, 1982. NPS photo. |

These [city police] did not recognize their duty as protecting trees and visitors. And I think I can see it. They received compensatory time, not overtime pay, for working the fair. If tomorrow morning I wanted the rangers to be down at city hall and they said "Why are we down here?," and we said, "Well, they are going to have a Strassenfest and I want you to protect city hall." They'd say what the devil are the city police doing? So, you had a little bit of this. The police were good for a deterrent. You always had the potential, the possibility, of a riot breaking out or something. So, we brought in . . . twenty five or thirty rangers, which we paid out of emergency funds. . . . [We had] to bring [people in] from everywhere, [because] a lot of parks had things going on around the Fourth of July. Some people didn't want to let them go. So quite often we had to pay for people to fill in behind them. The air fare got expensive. I suggested to the VP Fair that they go to TWA and see about getting some passes, and actually at times they gave them as much as $25,000 worth of freebies. I didn't realize how complicated it was until we got into it because TWA does not have a reciprocating agreement between every airline. And we'd be bringing some [rangers] out of Washington state or somewhere, and they'd have to catch a little hop, and then catch another line. . . . Almost consistently Don Morrison, one of the vice presidents of TWA, took it upon himself to sit down and oversee these arrangements.

It was an interesting learning situation for the rangers that came in. I remember going to Isle Royale and running into one of the wilderness rangers and we recognized each other because he had been [at the VP Fair] just a few months before. And I asked him what the experience was like. He said at first he just couldn't picture it, but he said now he wouldn't take anything for the experience he got. . . . You know, you had an opportunity to interact with just mobs of people. I would say maybe three to four hundred thousand sometimes at one time in a given area, when the big performances were going on. And our first two years, we had too many performances on the main stage. Something was going on the main stage every hour, from eleven in the morning until nine at night when the fireworks would start up. Those were tough times. But during the years we have sophisticated it. . . [20]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/adhi2-3.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004