|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Most Splendid Carpet |

|

I. A MASTERPIECE FOR THE SENATE

On September 21, 1789, Robert Morris of Pennsylvania rose before the Senate of the United States, meeting in New York, to offer to Congress "the use of any or all the public buildings in Philadelphia, the property of the State, in case Congress should, at any time, incline to make use of that city for the temporary residence of the Federal Government." [1] So began a year-long debate, which elicited cries of anguish from New Yorkers who wanted their Federal Hall to remain the seat of government, and determined lobbying from Robert Morris, who insisted on Philadelphia. Rufus King of New York thought the effect of moving to Philadelphia would be to "convulse the union," and Thomas Fitzsimons, a Pennsylvanian himself, feared stones would be thrown at him in the streets if he were there. [2] Even George Washington had second thoughts, finding that indications of "a spirit too imperious" had appeared there. [3]

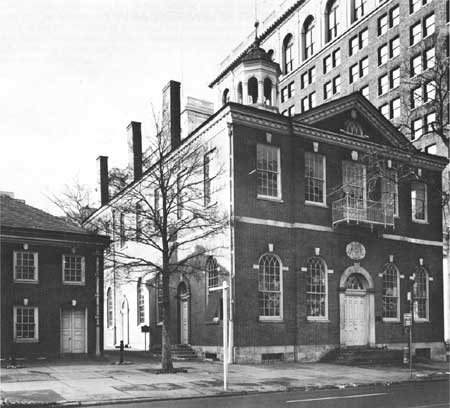

But Robert Morris prevailed, and on December 6, 1790, Congress met for the first time in Philadelphia, which would, by compromise, remain the temporary seat of government until the permanent Capitol in Washington, D.C., was made ready. Philadelphia did not accept lightly the task of making the Senators and Representatives comfortable in the city. After some consideration, the City and County Commissioners settled on the County Courthouse, (now known as Congress Hall), one of the newest public buildings in Philadelphia. Constructed between 1787 and 1789 in the Georgian style, it was balanced in 1790-91 by the building of a new City Hall at Fifth and Chestnut Streets, with the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) situated between them. Thus all levels of government were located in one city block, fulfilling Andrew Hamilton's ideas for a unified government center.

|

| FIGURE 1: Exterior view of Congress Hall looking southwest from Chestnut Street. Photo by James L. Dillon & Co., 1969 |

There was no question that the new Capitol would have tasteful furnishings, in simple classical form, as current fashion prescribed. The rooms themselves were rather plain, with white walls, pine floors, and fireplaces faced with marble. In the House of Representatives, a platform was erected for the Speaker's chair, following Parliamentary tradition, and the Representatives' chairs were placed in three tiers, each elevated above the preceding row for easy visibility. Mahogany desks, and chairs covered in black morocco leather were ordered from one of Philadelphia's finest cabinet-makers, Thomas Affleck, and Venetian blinds and colorful ingrain carpeting were installed. [4]

The Senate Chamber was even more elegant with individual desks, red leather upholstered chairs, crimson silk damask canopies and window draperies, pilaster decorations, and a dentilled cornice. Jacob Hilzheimer was not alone in considering the furnishings of the Senate Chamber "unnecessarily fine," when the Senators held their first full session there in December 1790. [5] But it was not until June 1791, that the Senate Chamber received its most elegant and impressive element of furnishing, a carpet of the "Axminster kind," "executed in a capital stile with rich bright colors" giving "a very fine effect," according to a contemporary account.

In the latest neoclassical fashion, it had three compartments. The central, nearly square section was of black pile, while the two rectangular side sections were rendered in green. Instead of having an overall design of flowers as in earlier eighteenth century carpets, it was geometric in composition and strictly symmetrical, with the United States Seal as the central motif, surrounded by a chain of the thirteen state shields. Cornucopias decorated the corners, displaying an abundance of corn, wheat, melons, and flowers, symbolizing the peace and prosperity which was now settling over the nation. In the side panels were trophies, assemblages of farming tools and fishing implements, to proclaim the abundance of natural resources.

Hand-knotted on a monumental scale of 22 by 40 feet, the Senate carpet was an impressive production, one of the most ambitious carpet-making projects ever undertaken in the United States, and one of the earliest. It came from the Philadelphia Carpet Manufactory at 458 North Second Street, the first full-fledged commercial carpet factory in America, where William Peter Sprague, an Englishman from Axminster, Devonshire, had established a promising business. Sprague had been trained in the Axminster technique of hand-knotting, probably at the factory of Thomas Whitty in Devonshire, England, and after establishing his own manufactory in Philadelphia in 1790 he used the technique for everything from small bedside carpets to at least two famous large carpets, one for Washington's residence at 190 High Street, and one for the Senate Chamber.

The technological marvel of such an impressive and stylish carpet was not lost on Americans. One observer wondered why the factory had received so little notice. It was just the sort of infant manufacture that Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton hoped could help the United States escape dependence on foreign imports, bring money to the treasury, and employ American workers.

As a work of art, the carpet took on an even deeper meaning. Its patriotic symbols and its neoclassical design reflected a developing American culture, with its optimism and its yearning for peace and order based on classical ideals. It brought to mind the Senate of ancient Rome, with which the United States Senate liked to compare itself, and it exemplified the American predilection for selecting those classical ideas and motifs which would best express American desires, and transposing them to suit the American context.

The carpet received its first public notice on March 5, 1791, in a satirical article in the Philadelphia Independent Gazeteer describing the furnishings of the room. A slightly irreverent tone marks the author of these words as one of those who thought of the Senators as perhaps a little too aristocratic and of the Chamber as a little too elaborately done up.

"Morgan: ... Have you seen Federal-Hall, Uncle Gwynn?

Uncle Gwynn: Yes I have. ... I have seen the stuffed seats; I have examined the curtains; I looked at the writing desks of the most shining mahogany; the superb drawers, for every Member to lock his brains, memory, and other documents in—and pray, Cousin Morgan, why would not windsor chairs have answered as well as those stuffed with hair?

Uncle Gwynn: Pray Cousin, where is the Bald Eagle and the 13 stars to be placed?

Morgan: On the floor, on the most splendid carpet that ever was made, our own manufactory too....

Morgan: Why Uncle, if a fine large Eagle and Thirteen Stars, had been painted on any Visible part of Federal-Hall, nobody in the Gallery would have looked at a single Member of Congress."

On June 6, 1791, a more complimentary article appeared in Dunlap's American Daily Advertiser describing at length the new carpet.

"Amongst the many accounts of the flourishing state of the infant manufactures of America, it seems strange that the Carpet Manufactory has been hitherto so little noticed. A correspondent who has lately visited that establishment in the Northern Liberties, informs us, that he has seen some of the carpets manufactured there by William Peter Sprague, of those durable kind called Turkey and Axminster, which sell at 20 per cent cheaper than those imported, and nearly as low as Wilton carpeting, but of double its durability.

The Carpet made for the President, and others for various persons, are masterpieces of their kind, particularly that for the Senate Chamber of the United States. The device wove in the last mentioned is the Crest and Armoreal Atchievements appertaining to the United States. Thirteen Stars, forming a constellation, diverging from a cloud, occupy the space under the chair of the Vice-President. The AMERICAN EAGLE is displayed in the centre, holding in his dexter talon an olive branch, in his sinister a bundle of thirteen arrows, and in his beak, a scroll inscribed with the motto E PLURIBUS UNUM. The whole surrounded by a chain formed of thirteen shields, emblematic of each state.

The sides are ornamented with marine and land trophies, and the corners exhibit very beautiful Cornucopias, some filled with olive branches and flowers expressive of peace, whilst others bear fruit and grain, the emblems of plenty.

Under the arms, on the Pole which supports the Cap of Liberty, is hung the Balance of Justice.

The whole being executed in a capital stile, with rich bright colours, has a very fine effect, notwithstanding the raw materials employed, are of the refuse and coarser kind; so that this manufactory is an advantage to others by allowing a price for those articles which could not be used in the common branches of woollen and tow business.

Manufactures of all kinds will generally meet with the support of the friends of the country, and this in particular, which already gives employment to a number of poor women and children, will no doubt be encouraged. The article of carpeting is now imported in considerable quantities, for which, large sums are annually exported to Europe; but if due encouragement be afforded, there is every reason to believe that it may become an object of exportation."

* * *

Work to ready the Philadelphia Court House for Congress had begun even before a final decision was reached on removal from New York. A three-member committee, Miers Fisher, William Colliday, and Matthew Clarkson, took on the job of planning for the reception of Congress, ordering materials and supervising work in progress in the House and Senate Chambers. Structural and architectural work was begun concurrently with the planning and ordering of furniture. Vouchers for 1790 include payments for carpentry work, installation of Franklin stoves, plastering and whitewashing, and the purchase of mahogany for tables and chairs and goatskins and finished morocco leather for upholstery. It is probable that the Senate carpet was designed and ordered from William Peter Sprague about the same time. That the carpet was not installed until some time between March and June of 1791 is not surprising, since several months were required for the preparation of a design and for the painstaking work of hand-knotting. In one of the last bills on the list of disbursements for the renovations of what had now begun to be called Congress Hall, William Peter Sprague was paid £156.12.6 for the 132-1/2 yards of carpeting he had made.

Slightly more than a pound per yard was expensive. By contrast, one nearly new ingrain carpet owned by John Todd, Jr., in Philadelphia was valued at 5 shillings 6 pence per yard in 1793; while in 1799 Josiah Lusby was selling ingrain carpeting at 9 shillings per yard in his store in Third Street. A new Wilton carpet in the inventory of Joseph Reed in 1785 was valued at 15 pounds for a 5-1/2 yard piece, or about 9 shillings per running yard.

The carpet itself was probably made in strips twenty-seven inches wide, and sewn together lengthwise. This was an unusual method for making a hand-knotted carpet, although it was customary for the less luxurious Brussels, Wiltons, and ingrains. An Axminster carpet was generally made in one piece on a loom the width of the intended rug. But 132-1/2 square yards of carpet would have been too large for the Senate Chamber floor, while eight 27 inch strips and two narrower ones for the border, measuring 132-1/2 running yards, fit the floor exactly. Corroborative evidence to support this hypothesis comes from a payment recorded in the City and County Commissioners' disbursements list for 1791 to William Bankson, an upholsterer, for "making a large Carpet," the eighteenth century term for sewing a carpet together; he also delivered 50 yards of green cord, which he may have used as binding.

Even before Congress arrived in Philadelphia, its members may have realized that Congress Hall would soon need to be enlarged, since the census they were planning for 1790 "to enumerate the citizens of the United States" would certainly increase representation in the House. By 1793, following reapportionment and with the addition of Vermont and Kentucky to the Union, there were 105 instead of 68 members of the House, and four additional Senators. The space problem became acute, and in April 1793, work began to extend the building 28 feet at the south end. Carried on throughout the terrible Yellow Fever epidemic of the summer, construction was completed by December, and Congress returned to a much larger Representatives Chamber and a rearranged second floor. Two committee rooms now stood between the old offices facing north and the Senate Chamber on the south end, and the Chamber itself was increased in size to 47 by 31 feet.

|

| FIGURE 2: Floor plans of Congress Hall, 1790 and 1793. |

With the six foot increase in width, some 282 square feet in total area, the Senate carpet lost some of its impact. It was too small for the space, leaving too much bare floor around the edges, and must have looked out of proportion, for William Peter Sprague came in to make repairs.

On December 2, 1793, Sprague submitted his invoice for £49.9.6 for "attending the cleaning carpets of the Senate room," and "fixing and repairing the same." Not only was the carpet repaired, but because of the greater floor area, Sprague added "a Black ground carpet 21-1/2 yds," and "a Green ditto 20 yds," and "two small Carpets for each of the Corners." Interestingly, the carpet was not rolled up and taken away for these adjustments, but Sprague himself and two boys spent a total of five days working in the "Senate room," as they called it, sweeping, washing, and mending some areas of the carpet. [6]

All the known facts about the Senate carpet are derived from the preceding four documents, the two newspaper articles and records of Sprague's bills. After 1793 it is not mentioned again. In 1795, after much debate, a public gallery was added to the north end of the room. The supporting pillars for this gallery intruded eight feet into the floor space, necessitating more changes in the carpet, either requiring that it be cut down, or that holes be cut in it for the columns. Although Congressman Theophilus Bradbury of Massachusetts noted in 1795 that there was indeed a woolen carpet in both Senate and House Chambers, he did not describe either of them, even as he remarked that the Senate Chamber was much more elegant than the House. None of the existing vouchers refers to carpeting at all at this date, nor is there any mention of it in contemporary newspapers. Likewise, no mention of carpeting appears in vouchers for work done in 1796, when the Senate Chamber floor, so hastily built in 1793, threatened to collapse and was entirely removed and relaid.

On May 14, 1800, Congress sat for the last time in Philadelphia. In June its effects were shipped to Washington, packed into coastal sailing ships which landed at Baltimore and at Alexandria. The Senate carpet was not listed among the crates and boxes which finally arrived in the muddy streets surrounding the permanent Capitol, and no indication of its fate has been found.

Since it belonged to the State of Pennsylvania, which had reimbursed the County and City Commissioners for their expenditures in 1791, it is not surprising that it was missing from Congressional packing lists. On the other hand, there is no word of it in Pennsylvania state accounts, where it might be expected to appear. Some of the Thomas Affleck chairs and desks were taken to Lancaster for the Pennsylvania state legislature in 1802, when the state capital was moved, but some were sold along with other furnishings from both House and Senate Chambers. It is entirely possible that the carpet had simply worn out after years of hard use, or it may have been cut up and sold, something which frequently happened to carpets when parts became worn and unsightly. [7]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

anderson/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 30-Nov-2007