|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

An exterior view of Fort Stedman as it appeared

in 1865.

Courtesy, National Archives.

The South Strikes Back— The Battle of Fort

Stedman

By mid-March of 1865 the climax of the campaign, and of the war was close at hand. Lee's forces in both Richmond and Petersburg had dwindled to under 50,000, with only 35,000 fit for duty. Grant, on the other hand, had available, or within easy march, at least 150,000. Moreover, Sheridan, having destroyed the remnants of Early's forces at Waynesboro, Va., on March 2, had cleared the Shenandoah Valley of Confederates and was now free to join Grant before Petersburg.

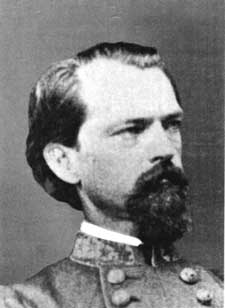

Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, Confederate commander at the Battle of Fort Stedman. Courtesy, National Archives. |

Everywhere Lee turned the picture was black. Union forces under Sherman, driving Johnston before them, split the Confederacy and were now in North Carolina. With President Jefferson Davis' consent, Lee sent a letter to General Grant on March 2 suggesting an interview. In the early morning hours of the second day following the dispatch of the letter, Lee and Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon discussed the three possible solutions to the problem which perplexed them. In order, they were as follows:

(1) Try to negotiate satisfactory peace terms. This had already been acted upon in Lee's note to Grant.

(2) Retreat from Richmond and Petersburg and unite with Johnston for a final stand.

(3) Attack Grant in order to facilitate the retreat.

There followed a series of interviews with high Government officials in Richmond. Each of the plans was analyzed. The first was quickly dropped when Grant made it clear that he was not empowered to negotiate. Nor was the second proposal, that of retreat, deemed advisable by President Davis who wished to strike one more blow before surrendering his capital. This left only the third alternative—to attack.

The plan evolved by the Southern commander was relatively simple. He ordered General Gordon to make a reconnaissance of the lines around Petersburg. Gordon soon reported that the best place for the proposed attack was at Fort Stedman. This Union position was near the City Point Railroad which Grant used as a major supply line between his base at City Point and the entrenchments around Petersburg. Capture of this railroad would cut the Northern supply line. An additional advantage, from the Confederate viewpoint, was the fact that Fort Stedman was but 150 yards to the east of a strongly fortified Southern position named Colquitt's Salient.

About one-half of the besieged army would be used to charge the Union line in the vicinity of Fort Stedman. It was hoped that this would cause Grant to shorten his front in order to protect the endangered supply route. Then Lee could detach a portion of his army to send to the aid of Johnston as, with shorter lines, he would not need as many men in Petersburg. Should the attack fail, he would attempt to retreat with his forces intact for a final stand with Johnston. This was the last desperate gamble of the Army of Northern Virginia.

The details for the attack were worked out by Gordon. During the night preceding the attack, the obstructions before the Confederate lines were to be removed and the Union pickets overcome as quietly as possible. A group of 50 men were to remove the chevaux-de-frise and abatis protecting Fort Stedman; then 3 companies of 100 men each were to charge and capture the fort. When Stedman was safely in Confederate hands, these men were to pretend they were Union troops and, forming into 3 columns, were to rush to the rear to capture other positions.

The next step was to send a division of infantry to gain possession of the siege lines north and south of the fallen bastion. When the breach had been sufficiently widened, Southern cavalry were to rush through and destroy telegraphic communication with Grant's headquarters at City Point. They were also ordered to cut the military railroad, Additional reserves were to follow the cavalry.

The attack was scheduled for the morning of March 25. The 50 axe-men and the 300 soldiers who were to make up the advance columns were given strips of white cloth to wear across their breasts in order to tell friend from foe. The officers in charge were given the names of Union officers known to be in the vicinity and were told to shout their assumed names if challenged. Beginning about 3 a. m., Confederates professing to be deserters crossed to the Union pickets with requests to surrender. Their actual purpose was to be near at hand to overwhelm the unsuspecting pickets when the attack began.

At 4 a. m. Gordon gave the signal, and the Confederates sprang for ward. At first the attack went as planned. Blue-clad pickets were silenced so effectively that not a shot was fired. Union obstructions were quickly hewn down by the axemen, and the small vanguard of 300 swept through Battery 10 which stood immediately north of Fort Stedman. They then rushed into the fort from the northwest. The sleeping, or partially awakened, occupants were completely surprised and surrendered without a fight. Battery 11 to the south of Fort Stedman was also soon in Confederate hands. Union resistance in this early stage was ineffective, although Battery 11 was recaptured for a brief time.

More Confederates pressed into the torn line. While the three columns set our in the general direction of City Point and along the Prince George Court House Road behind Stedman, other infantry units moved north and south along the Federal emplacements. To the north they captured the fortifications as far as Battery 9 where they were stopped by the Union defenders. In the opposite direction they progressed as far as the ramparts of Fort Haskell. A desperate struggle ensued, but here, too, the Northerners refused to yield. Despite these checks, the Confederates were now in possession of about three-fourths of a mile of the Union line.

In the center of the Confederate attack the three small columns quickly advanced as far as Harrison's Creek a small stream which winds its way north to the Appomattox River 650 yards behind Fort Stedman. One of the columns succeeded in crossing the stream and continuing toward a small Union artillery post on the site of what had been Confederate Battery 8, but canister from the post forced the column back to the creek. Confusion took hold of the Confederates who were unable to locate the positions they had been ordered to capture in the rear of the Union line. Artillery fire from Northern guns on a ridge to the east held them on the banks of Harrison's Creek. By 6 a. m. their forward momentum had been checked.

Union infantry then charged from the ridge to attack the Southerners. The forces joined battle along the banks of Harrison's Creek and the Confederates were soon forced back to Fort Stedman. For a brief time they held their newly captured positions. At 7:30 a. m. Gen. John F. Hartranft advanced on them with a division of Northern troops. Heavy musket and artillery fire on Gordon's men threatened them with annihilation unless they retired to their own lines soon. Shortly after 7:30 a. m., Gordon received an order from Lee to withdraw his men. The order was quickly dispatched across the open fields to the soldiers in the captured Union works. By now, however, the line of retreat was raked by a vicious crossfire and many Confederates preferred surrender to withdrawal. About 7:45 a. m., the Union line was completely restored and the forlorn Southern hope of a successful disruption of Northern communications, followed by secret withdrawal from the city, was now lost. Equally bad, if not worse, to the Confederates was the loss of more than 4,000 killed, wounded, and captured as compared to the Union casualties of less than 1,500.

Of the three Confederate plans of action before the Battle of Fort Stedman, now only the second—retreat—was possible. The situation demanded immediate action, for, even as Gordon had been preparing on March 24 to launch his attack, Grant had been engaged in planning more difficulties for the harassed defenders of Petersburg.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |