|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Gaslighting in America A Guide for Historic Preservation |

|

PLATES

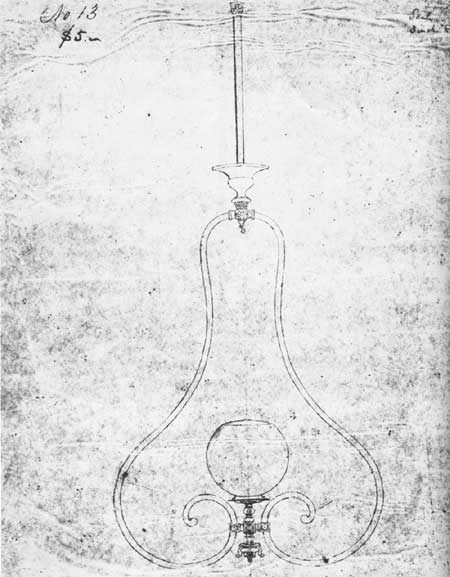

| Cornelius and Baker, harp shaped hall pendant by J. G. Bruff, the Treasury Building, 1859. | Plate 60 |

This hall pendant measured approximately 2 feet wide by 4 feet high and cost $5. Among the Bruff scaled drawings in the National Archives there is one for a slightly larger and rather ornate hall pendant that was to cost $10. The design of the more expensive example was somewhat similar in concept to Fellows and Hoffman's no. 145 reproduced on plate 43 of this report.

The key of the simple pendant shown here, and those of the "T" on plate 59, were designed to have the maker's label in the plain center space: "Cornelius and Baker" on the obverse, and "Philadelphia" on the reverse. Hall pendants of this form were called "lyres," or "harps," or some times "lyras" in the last century. The use of so-called "hall pendants" was by no means confined to halls, however, as the example of James Beck's dry goods store in New York has already demonstrated (see plate 30).

|

| From the National Archives, Record Group No. 121. (click on image for a PDF version) |

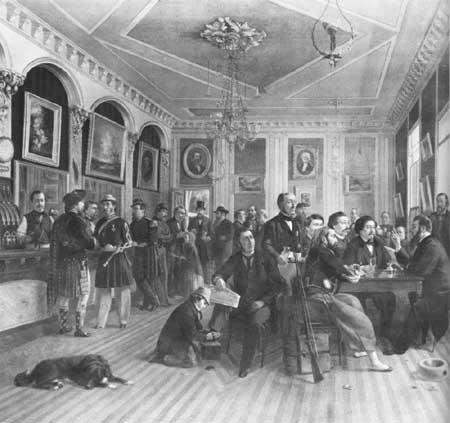

| Painting of a New York City saloon interior, 1863. | Plate 61 |

This painting by E. D. Hawthorne in the New York Historical Society shows the interior of George Hayward's Porter House at 187 Sixth Avenue in 1863. [97] Carefully detailed genre paintings such as this are invaluable sources of documentation for their periods. Once the eye has taken in the picturesque variety of New York officers' uniforms, including the Highlander (79th New York Volunteers) at the left and the Zouave in the foreground, other fascinating details become apparent. Among the details are the beer pump at the left, the fly screen at the right, the parquet flooring of alternating light and dark-stained wood, and, certainly not least, the lighting fixtures. [98]

The gilded chandelier and pendants were furnished with smoke bells of porcelain or glass, probably the former since glass is more vulnerable to heat. The chains ornamenting the chandelier were already out of fashion by 1863. Note the manner in which the smoke bells are suspended over each burner. With the exception of lyres, which were almost invariably supplied with a smoke bell because the stem was directly over the burner, smoke bells were not very often used in domestic interiors. However, they were frequently used in saloons, probably to protect frescoed ceilings not only from gas fumes but also from the heavy cigar smoke that was drawn upwards by the convention of lighted gas jets. [99] Though the pendants shown here appear at first glance to be lyres, it is an illusion resulting from the perspective rendering. Actually, they are a most unusual type — two-light pendants with lyraform centers.

|

| Courtesy of The New York Historical Society, New York City. (click on image for a PDF version) |

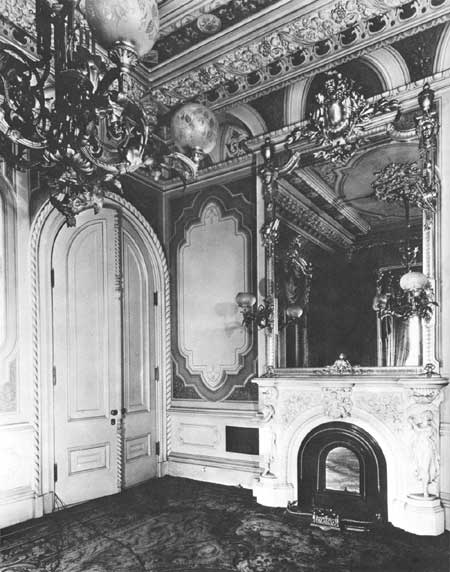

| Music Room chandelier, Morse-Libby House, Portland, Maine, 1863. | Plate 62 |

Then the Morse-Libby House (now called Victoria Mansion) was completed in Portland, Maine, in 1863 for Ruggles Sylvester Morse, it was supplied with chandeliers and brackets as splendid an any in America. Unfortunately, no maker's mark appears on them. The 12-light drawing room chandelier and this six-light example in the music room are magnificently executed in gilded bronze. They are, however, among the last important fixtures made in the lavish Neo-Rococo style so fashionable during the 1850s. With the possible exception of the very grand bronze finished chandeliers of Stanton Hall in Natchez, Mississippi, completed in 1857, no extant gas fixtures in America that were designed for domestic use exceed the Morse-Libby chandeliers in scale or complexity of ornament. [100] The globes seen here are original. Note that their holders admitted very little air, being pierced by only a few small holes.

|

| From the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Cornelius and Baker three branch cast-iron chandelier, ca. 1860. | Plate 63 |

Cast-iron chandeliers were made in quantity during the 1860s. They were less expensive than the brass or bronze products, as the material itself was very cheap. The major disadvantage of cast-iron fixtures was their weight. This three-branched example by Cornelius and Baker weights 20 pounds as against less than 5 pounds for a brass fixture of comparable size. It has been shortened 6 inches by the removal of one section of lacquered brass sleeve and the cast-iron collars at each end of that piece. The remaining identical section and its collars may be seen on the stem just below the three-handled top ornament. The branches and the palmette-ornamented elements from which they extend are all cast in one piece. These branches, like those on plates 35, 36, 38, 40 and elsewhere, are of the open trough type, leaving the gas tube visible from above. Three kinds of branches were in general use: the open trough type just mentioned; the two-mold cast type shown on plates 18, 26, 76 and others; and the tubular type, usually entwined with ornament, of which examples may be seen on plates 24, 25 and elsewhere.

The eclectic style of this chandelier was probably classified in its own day as "Renaissance." Among the cast ornaments are four lion heads, three dog heads, and three gilded brass Greek palmettes. The other brass parts are burnished and lacquered. The turned brass shade holders are inaccurate modern replacements. The originals would have been pierced with air holes. The shades themselves date from the right period, although they are not original to this chandelier. they are acid-etched with the same Neo-Grec griffin pattern that is frosted on the later shades of the chandelier on plate 24. Their necks have a diameter of 2-1/2 inches; they are 6-1/2 inches high; and the diameter of the openings at the top is 5-1/2 inches. Their tops are rimmed with gilt copper.

|

| From the author's collection, photograph by Jack E. Boucher. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Details of chandelier in plate 63 showing labeled gas key. | Plate 64 |

These details showing the obverse and the reverse of a gas key on the fixture in plate 63 have been enlarged for legibility. The key itself measures only 1-1/8 inches across. Many other Cornelius and Baker chandeliers were marked this way as well, and the design of the key remained similar, whether it was of cast brass or cast iron. As the firm name remained the same for 18 years, precise dating based on the wording of the mark is not possible.

During most of the 1860s the advertisers taking the best display space in The American Gas Light Journal were Cornelius and Baker and the New York firm of Mitchell, Vance and Company. A Fellows, Hoffman and Company advertisement often occupied the next best spot. This confirms indications that these three were the leading firms of the decade. Evidence to be mentioned later will show that by 1876 Mitchell, Vance and Company had surpassed Cornelius and Baker and achieved the leading position.

In 1868 the Philadelphia firm's partnership was composed of Robert Cornelius, Isaac F. Baker, William C. Baker, Robert Comeley Cornelius, John C. Cornelius, Robert C. Baker, and Charles E. Cornelius. During 1869 the famous partnership formed in 1851 was dissolved, and by 1870 Cornelius and Baker had become Cornelius and Sons.

|

| From the author's collection, photograph by Jack E. Boucher. (click on image for a PDF version) |

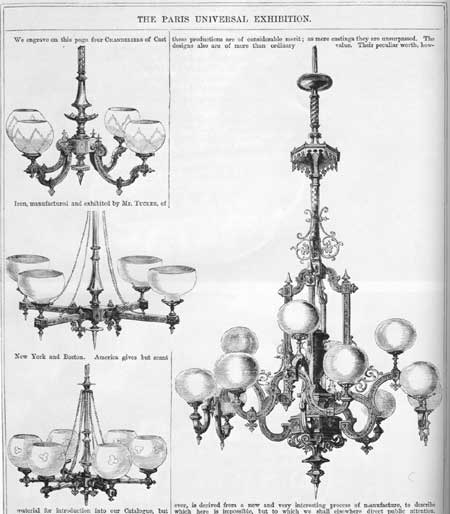

| Engraving of Tucker Manufacturing Company cast-iron chandeliers in the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867. | Plate 65 |

The only American gas fixtures mentioned in the catalogue of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867 published by the Art-Journal were those illustrated here by the Tucker Manufacturing Company of New York and Boston. [101] Further significant recognition was accorded the firm (actually headed by Thomas J. Fisher) about a year later when Alfred Bult Mullett, then Supervising Architect of the Treasury Department, commissioned the Tucker Manufacturing Company to make the fixtures for the new north wing of the Treasury Building in Washington. Among the fixtures were those for the lavishly ornamented Cash Room, the setting for President Grant's first inaugural ball. The Treasury boasted, possibly with less than complete justification, that the Cash Room was "the most costly room in the world." [102]

The rather condescending text of this illustration reads as follows:

We engrave on this page four Chandeliers of Cast Iron, manufactured and exhibited by Mr. Tucker of New York and Boston. America gives but scant material for introduction into our Catalogue, but these productions are of considerable merit; as mere castings they are unsurpassed. The designs are of more than ordinary value. Their peculiar worth, however, is derived from a new and very interesting process of manufacture, to describe which here is impossible, but to which we shall elsewhere direct public attention. [103]

Cast iron enjoyed so great a vogue during the 1850s and 1860s that it is not astonishing to find it used for such elaborate gaseliers as that on the right. Although its best known use was for architectural elements, including entire facades, fences, garden furniture and the like, cast iron was so popular that it was even used for indoor furniture such as hall stands, small tables, plant stands, and footstools, among other things.

These cast-iron fixtures are in the latest style current at the time of their exhibition. They are austerely stiff and angular compared with their earlier counterparts and presage the Eastlake manner soon to follow. Although Charles Locke Eastlake would not have given full approval to the chandelier at the right, he would probably have found the middle and lower fixtures at the left sufficiently "honest" in their expression of "constructive principles" to merit approbation. [104] Even the most elaborate of these gaseliers with its tight and rigid curves evidences a strong reaction against the lush mode of the preceding decade.

|

| From the author's collection. (click on image for a PDF version) |

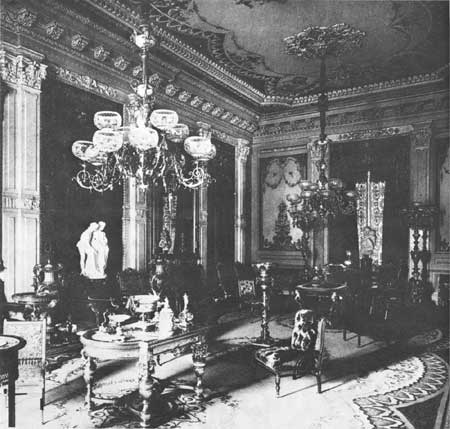

| Drawing room of A. T. Stewart's Mansion, New York City, 1869. | Plate 66 |

When it was completed in 1869, Alexander Turney Stewart's marble mansion on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street was popularly regarded as the most sumptuous residence in New York City. [105] The hall, reception room, music room, and master chamber had 12-light bronze chandeliers of similar, if not identical, conventionally ponderous design. The drawing room chandeliers shown here, while equally complex in design, are much lighter and more delicate in treatment. The branches have the elaborate but slender character that became so fashionable toward the end of the century. In that respect, they are forward looking. Note the urn-like porcelain elements ornamenting the stems of these fixtures. They portend a more wide-spread use of porcelain on chandeliers during the following two decades.

At first glance, the shades appear to be of the type that came in around 1880, but close scrutiny reveals that they still have the very constricted necks of an earlier date. Note that they are very lightly etched. Their delicate patterning leaves them, for all practical purposes, almost clear.

The standing fixtures, or "lampadaires," flanking the far window were not commonly found except in the most lavish domestic interiors of the period. They solved the problem of achieving extra light without using brackets, which would have interfered with the frescoed design of the wall panels. All the Stewart Mansion fixtures, of course, were exceptional in both scale and grandeur.

|

| From the Library of Congress. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Library of A. T. Stewart's Mansion, New York City, 1869. | Plate 67 |

The chandeliers in the library of A. T Stewart's mansion had more angular branches, Egyptian Revival heads, stiff palmettes, slender beaded chains, and elaborate colonnettes—all typical Neo-Grec elements of the Neo-Renaissance style (now frequently called "Centennial Renaissance") that flourished from the mid-1860s until after 1876. Chandeliers with clusters of fancifully formed rods or colonnettes arching out from the central stem and surrounding it were very fashionable during the 1870s. [106] However, the most significant innovation to be seen on these Stewart Mansion fixtures of 1869 is the double cone reflector at the base of each chandelier. The construction and function of mirrored reflectors of this type will be discussed later in plates 86, 87, and 88. They were adjustable, permitting light to be aimed and concentrated at will.

Unlike the library, the famous picture gallery in the Stewart Mansion was provided with gas reflector fixtures alone, without conventional burners. [107]

|

| From the Library of Congress. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Section through a mansion showing mechanism of a Springfield Gas Machine, ca. 1868. | Plate 68 |

So-called "portable gas works" or "portable gas machines" were in use as early as 1813, when David Melville of Newport, Rhode Island, patented a gas machine in March of that year. In 1846, the Long Island Sound steamboat Atlantic had portable gas works aboard. [108] They were used principally to generate gas for consumption where centrally manufactured gas was not available. Occasionally, establishments using large quantities of gas found it economically advantageous to generate their own illuminant even when commercial gas was at hand. That was the case with the 600-room St. Nicholas Hotel of 1854 in New York City, as a contemporary advertisement relates:

A spacious private gas-house, capable of furnishing 200,000 cubic feet of gas per night, supplies the hotel with the material of light. This building, like the steam generating department is also detached from the main structure. [109]

Another advertisement says:

The gas light here is made from resin and costs only $924 a month, whereas if the hotel bought it from the gas companies it would cost over $2,500 for the same period yet it does brightly illuminate all the rooms and for those who understand its workings, is no menace at all. [110]

Various substances, including some extremely volatile and dangerous ones, were used to supply gas machines. James J. Walworth's gas generating system for residences, churches and public buildings supplied gas made from resin and was in operation by 1850. [111] O. P Drake, a Boston manufacturer of chemical and "philosophical" (i.e., scientific) apparatus, advertised "Drake's Patent Hydro-Carbon Gas Generating Apparatus" in 1854. The apparatus was designed for "Private Dwelling Houses, Churches, Hotels and Factories, in the country, where coal gas can not be obtained without great expense." The distillate to be vaporized was "benzole" (benzine). Drake's prices ranged from $150 for a six-light apparatus to $800 for a 100-light one. [112] There were also devices for enriching coal gas by "carbonizing" or "carbureting" it. John Amsterdam patented a method of carbonizing illuminating gas on June 15, 1858. [113] This print, drawn and engraved by John Keim and published around 1868 by Hay Brothers, shows one of the celebrated Springfield Gas Machines installed. The mansion it serves, a grand example of mansard-roofed splender in the French Second Empire manner, is evidently imaginary, since, except for the hall, its elegant interiors are all drawing rooms. (There is not a dining room, library, or chamber to be seen among the parlors.) Note that the ample grounds of the magnificent imaginary estate contained at least three lamp standards and that the stable was also gaslighted. This was probably more advertising hyperbole than truth.

The Springfield Gas Machine appears to have been one of the most successful contrivances of its kind in use during the last third of the 19th century. It generated gas from gasoline, a fuel supplied by the company as early as 1865. [114] The explosive danger of vaporized gasoline was recognized by placing the generator, or evaporating tank, underground at a distance from the building or buildings to be lighted. Presumably the risk to the person whose duty it was to replenish the tank was accepted as the necessary price of "Progress," much as steam boiler explosions seem then to have been regarded. (Lest the last century be thought more callous than our own, it should be remembered that the carnage caused by automobile accidents now seems acceptable.) An air pump driven by a weight suspended from the cellar ceiling forced air through a pipe leading to the generator, and a second pipe conducted the gas from the underground tank to the house. [115] The apparent prevalence of "portable gas machines" clearly indicates that the absence of centrally manufactured gas in a community by no means precludes the possibility that structures in that community were, in fact, gaslighted.

|

| From the Library of Congress. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Painting of W H. Vanderbilt Parlor, New York City, 1873. | Plate 69 |

Visual documentation of American gaslighted interiors is relatively scarce. One of the best post Civil War genre paintings showing the effect of gaslight is this example painted in 1873 by Joseph Seymour Guy. It represents William Henry Vanderbilt and his family in the cozy back parlor of their bourgeois brownstone before their famous Fifth Avenue mansions and Newport "cottages" were planned. The room is lighted by a pair of angular brackets and a chandelier. The central light could be lowered for reading. A large and splendid unlighted glass chandelier is in the front parlor beyond the arched doorway. Note that the bronze candelabra of the mantel garniture are not being used. The library of Alfrederick Smith Hatch's house at Park Avenue and 37th Street in New York, shown in Eastman Johnson's 1871 painting of the Hatch Family, had a chandelier very similar to this W. H. Vanderbilt back parlor fixture. [116]

|

| Courtesy of the Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

myers/plate7.htm

Last Updated: 30-Nov-2007