|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Gaslighting in America A Guide for Historic Preservation |

|

PLATES

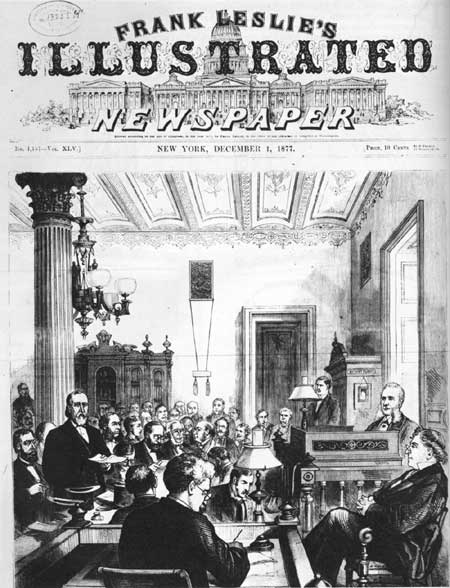

| Courtroom fixtures, New York City, 1877. | Plate 90 |

The chandeliers and brackets used in public buildings did not differ in design from those made for residential use, except for an occasional bit of symbolism, unless great size was called for, as in the case of theater auditorium chandeliers.

This wood engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper for December 1, 1877, shows the interior of the Surrogate's Court Room in New York City as it appeared on November 14, 1877, during the famous case contesting Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt's will.

Note that the chandelier looks much as expected of any six-branched ornate fixture of the period, with the possible distinction that the figurines above the bowl may have represented such abstractions as justice, prudence, law, etc. There is evidence in this picture of specialized use, i.e., the gaslamps on the judge's bench and the clerk's desk. The shades may or may not be reflectors, but the glass chimneys certainly indicate Argand burners, which gave considerably more light than the standard fishtail or batswing burners. Frequently desks, in public rooms where much writing was required, were furnished with gas Argand lamps.

|

| From the Library of Congress. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Von Ezdorf design for chandelier, State, War and Navy Building, 1876-1886. | Plate 91 |

The custom of designing gas fixtures specifically for important U.S. Government buildings continued until the end of the gas era. At least three drawings for lighting fixtures by Richard Von Ezdorf (1848-1926), the artist who designed most of the ornamental work in the former State, War, and Navy Building (now the Old Executive Office Building), have survived. [141] The Ezdorf design seen here is for a chandelier having two, four, or six lights. Its spread was 41 inches. The shields on the fixture, blank in this drawing, were to bear the insignia of the particular military personnel occupying the office, e.g., Army Engineers, Artillery, etc. A supplementary drawing lettered "B" shows four alternative shield designs. This chandelier has the decidedly stiff and rather spiky Eastlake character so congenial to the taste of the 1870s. It was designed between 1876, when Ezdorf was transferred to the War Department rolls, and 1886, when the need for new designs was filled. [142]

Another Ezdorf design is for a chandelier with two alternative designs for branches. Sea horses and sea monsters were included among the ornaments. Perhaps the most striking Ezdorf lighting fixture drawing is the one for brackets that are still extant in the former Navy Library, the so-called "Indian Treaty Room." They have been likened to nautical figureheads, an appropriate simile for a Navy Department room. The brackets are in the form of winged half figures of children symbolizing peace, war, liberty, science, industry, and other abstractions above which are horizontal bars holding three burners each. [143]

|

| From the National Archives, Record Group 42. (click on image for a PDF version) |

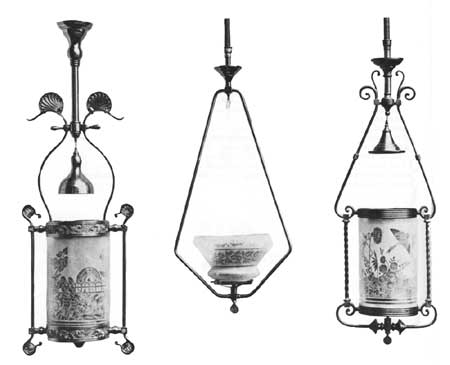

| Hall pendants by Thackera, Sons and Company, 1882. | Plate 92 |

In September 14, 1882, a package of 41 photographs addressed to George H. Elliot, Lieutenant Colonel of Engineers, was received in the Office of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army in Washington. The photographs, some of them "phototypes" by F. Gutekunst of Philadelphia, were from Thackera, Sons and Company, "Manufacturers of Gas Fixtures, Bronzes, &c." of 718 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia and illustrated 60 of their fixtures. [144]

Many of the fixtures illustrated in the 1882 package were obviously quite new, as the mounts to which they are affixed are stamped (not printed) "Thackera, Sons & Co." Others can be dated before 1882, as their mounts are printed Thackera, Buck & Co." All, however, appear to have been recently designed, as they show a marked departure from the Neo-Grec and misinterpreted Eastlake mannerisms current in 1876 and thereafter. It should also be noted that at this time all the shades, without exception, exhibited at the Centennial were of the small-necked variety, whereas each shade in the Thackera photographs is of the new wide-based type. That significant change therefore occurred between 1876 and 1881 at the latest. [145] The improved shade design, which greatly reduced or entirely eliminated flickering, was rapidly adopted, and many older fixtures were fitted with new shade holders to accommodate wide-based shades.

The earlier association of Benjamin Thackera with William F. Miskey and William O. B. Merrill in 1866 was discussed in plate 45 of this report. In 1871 or 1872, Thackera, Buck and Company was founded with Benjamin Thackera, William J. Buck and John H. Southworth as partners. By 1877, Charles Thackera and Byron H. Buck had joined the partnership, which continued to operate as Thackera, Buck and Company until sometime in 1881. In 1882 the firm was listed as Thackera, Sons and Company and did business under that name until sometime in 1887. The partners were Benjamin Thackera, John H. Southworth, Charles Thackera, and Alexander M. Thackera, until 1887 when Southworth left the firm. From 1888 until the turn of the century or later the firm was styled the Thackera Manufacturing Company. In 1900 the listing read "Thackera Manufacturing Co. Gas Fixtures 1606 Chestnut Street." [146]

The fixtures in the photographs are for the most part very avant garde for their date. They show a sophisticated awareness of artistic developments in England, where William Morris's reformist principles, Walter Crane's elegant stylizations and Edward W. Godwin's Anglo-Japanese designs (as well as the work of many others) were revolutionizing aesthetic perceptions. Many of the Thackera chandeliers have a well-proportioned lightness and elegance of design that was exceptional in American commercial work around 1880.

The three hall pendants shown here are typical Thackera designs of their period. Naturalism has been wholly abandoned in favor of stylization. The flowers and bird etched on the cylindrical shades are rendered in the Anglo-Japanese manner and were done at least three years before 1885, when Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado created a popular rage for japonisme. The sunflowers and other metalwork motifs of the left-hand pendant are derived from the English aesthetic movement, and the utter simplicity of the restrained fixture in the middle may owe something to William Morris's reforms. It depends entirely upon its subtle proportions for its handsome effect.

Of the 15 pendants illustrated in the photographs, three are of the square lantern type with clear glass sides, and three others, two of them square, are hung with spear prisms. One pillar and three standards may also have been intended for hall lights, as they are suitable for mounting on newel posts.

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-970 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

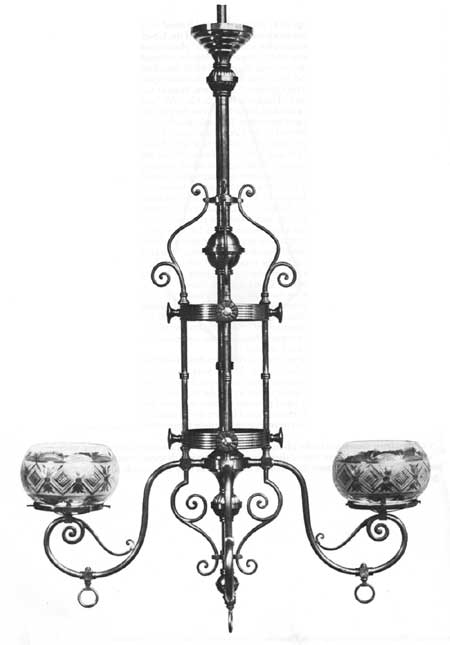

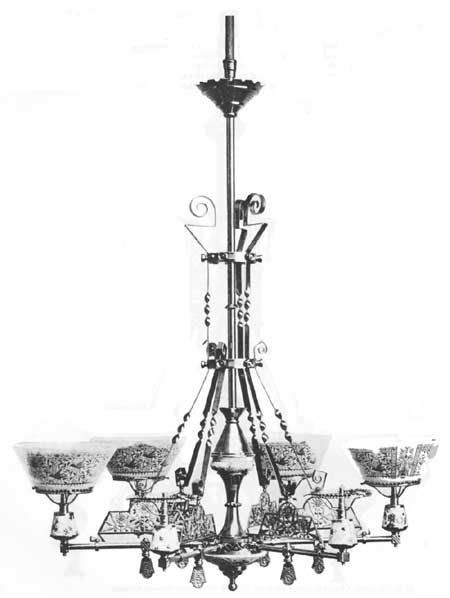

| Chandelier by Thackera, Sons and Company, 1882. | Plate 93 |

The photographs, or "phototypes," sent by Thackera, Sons and Company to Lieutenant Colonel Elliot in 1882 were not accompanied by any list of customers, satisfied or otherwise, as was common advertising practice, nor has any such list so far come to light. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the status of the firm in the trade as a whole, but the quality of their designs suggests that their standing was high among their more discriminating patrons. It is known that in 1876 Thackera, Buck and Company supplied the gas fixtures for Horticultural Hall, one of the two major permanent buildings erected for the Centennial Exposition. [147]

The restrained and elegant fixture on this plate is an example of Thackera work using tubular forms almost exclusively. The rectangularity so characteristic of design during the 1880s is not apparent here, but is found in various other Thackera designs as will presently be seen. This four-branched chandelier measured 49 inches high by 27 inches wide. Two of the burners and their accompanying shades and shade holders have been removed to show the design more clearly. Note that the shades are cut as well as partially frosted, thus providing brilliant refraction. Cut glass shades were more commonly used on crystal chandeliers of the period than on brass ones. They were among the rare and most expensive shades made, along with hand-painted ones.

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-863 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

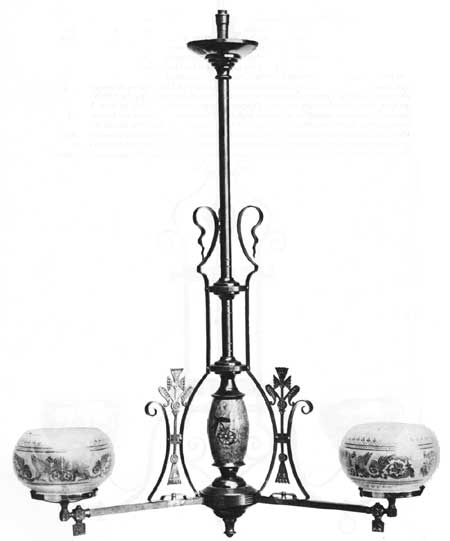

| Chandelier by Thackera, Buck and Company, ca. 1881. | Plate 94 |

In the Thackera photographs, 19 of the 60 fixtures, or just one less than a third, are ornamented with ceramic ornaments in the Japanese taste. Three of the four standards shown have fairly large vases, but most of the ornaments, like the one seen here, are relatively small. This small chandelier combines Eastlake metalwork of very flat profiles, angular outlines, and square sections with its Anglo-Japanese ceramic baluster. This eclectic combination of neo medieval and oriental forms is, however, blended to form a harmonious whole. The one element inconsistent with the design is the Neo-Grec griffin and rinceau pattern etched on the shades. That pattern was evidently very popular, as it appears on three other sets of shades in the Thackera photographs, as well as on the shades of two fixtures previously discussed (see plates 24 and 63 of this report). This three-branched fixture (one of the shades has been removed with its holder to clarify the illustration) was 3 feet high and 2 feet wide. "Thackera, Buck and Co.," is printed on the mount to which the photograph is affixed, indicating that this fixture must be dated no later than 1881.

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-890 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Chandelier with center slide, Thackera, Sons and Company, 1882. | Plate 95 |

If the 33 chandeliers in the Thackera photographs, 8 (like this one) have center slides. Rep resenting just under 25 percent of the total, this may indicate a waning popularity for center slides, which apparently tended to get out of order, judging from the many patent gadgets that claimed superiority over other presumably more troublesome models. This fixture was probably designed for a dining room or library. The stylized floral motifs, fan-like patterns, and spindle work galley of the metalwork combine Anglo-Japanese and Eastlake forms. The square gallery surrounding the slide fixture and its painted shade is reminiscent of similar spindle work found on furniture of the period. The size of this chandelier was 52 inches high with a 34 inch spread.

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-952 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Six-branched chandelier, Thackera, Sons and Company, 1882. | Plate 96 |

Few if any fixtures designed around 1880 in America were as up-to-date in their conformity with advanced artistic principles as this one from the Thackera collection. Two of the shades have been removed to show the design more clearly. The thin, twisted and spiraled brass trim and the cast-brass floral motifs, combined with the ceramic sections under the burners and decorating the stem, are more or less consistently in the Anglo-Japanese manner. Etched with a birds-in-bamboo pattern, the shades are most appropriate to the total design. This six-branched fixture measures 41 inches high by 27 inches wide.

The Thackera photographs may give a clue to the prevalence of various types of fixtures around 1880. Thirty-three of the 60 fixtures shown on the 41 pictures were chandeliers. Four were standards. Two were toilets, that is, small chandeliers on cantilevered brackets; and the rest were hall or two-branched pendants. As already noted, slightly less than a quarter of the chandeliers had center slides. Almost a third of the chandeliers and other fixtures (as noted) had ceramic ornaments in the Japanese manner. The most vital new design influence of the moment was there fore accorded ample recognition.

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-842 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

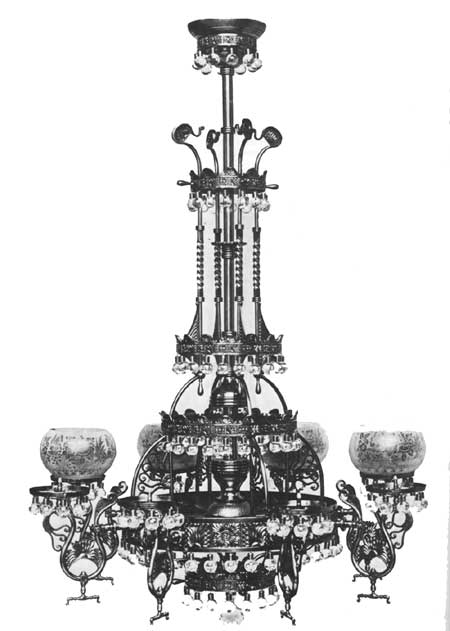

| Eight-branch, glass ornamented chandelier, Thackera, Sons and Company, 1882. | Plate 97 |

Only six Thackera chandeliers out of the 33 in the photographs have any glass ornaments at all, and those six that can in any way be classified as "crystal" do not resemble the more conventional glass examples previously discussed. Several have a far greater proportion of metal to glass than was formerly customary. Some have stems ornamented by thin brass arches studded with glass spear points. Others combine two types of prism in a single fixture. All are, to some degree, new and original. A Thackera, Buck and Company two-tiered fixture with notched spear prisms and a few glass bells in the form of fuchsia blossoms appears to have had silvered metalwork and was somewhat more conventional than the others.

The eight-light fixture illustrated here (four shades have been removed) is the most original of the glass-ornamented Thackera fixtures. Each annular element is fringed with glass balls, a design motif perhaps suggested by the textile ball fringe so popular for use on furniture and lambrequins during the 1870s and 1880s. So little glass is used, however, that it is moot whether or not this creatively inventive design should be termed a "crystal chandelier." This fixture was 4 feet high and had a spread of 26 inches.

It is worth noting that as early as 1882 at least one crystal chandelier was already imitating a late 18th-century English type. Thackera's no. 9560, a six-light example, had a base of concentric rings of prisms and cascades of faceted glass bead chains that descended from a crowning ring and flared slightly outward to the ring supporting the burners. The center stem was thus entirely concealed by the glass "basket." That style of chandelier, popular during the Federal period and even later, was very probably considered by ca. 1880 to be "Colonial."

|

| Courtesy of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Photo No. 77-F-156-44-953 in the National Archives. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| Six-light glass ornamented chandelier, ca. 1880. | Plate 98 |

This six-light chandelier, 6-3/4 inches taller than the eight-light one on the previous plate, is now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It originally hung in the dining room of William Ryan, a prosperous Dubuque, Iowa, meat packer who had the inelegant nickname of "Hog Ryan." One year during the 1880s Mr. Ryan's daughters had the family's dining room redecorated with new wainscoting, William Morris wallpaper, and this chandelier in the latest aesthetic taste. The flat, chrysanthemum pattern of the metalwork panels in the upper zone resembles similar panels shown on a chandelier, no. 720, in the I. P. Frink catalogues for 1882-1883, and on that basis this chandelier has been attributed to Frink. [148] However, the even closer resemblance between it and the Thackera chandelier on plate 97 should also be noted.

|

| Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edgar J. Kaufman Charitable Foundation Fund, 1969. (click on image for a PDF version) |

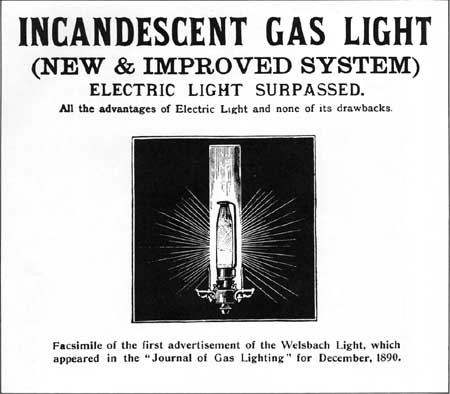

| The Welsbach burner competes with the electric light, 1890. | Plate 99 |

In October 21, 1879, Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) succeeded in making an incandescent electric light bulb that burned for over 40 hours. While it is an oversimplification to say that Edison invented the electric light, his improvements on earlier discoveries and his development of a central distributing system for the requisite current made electric light commercially feasible. By 1882, his famous Pearl Street Station's dynamos were supplying direct current over wires to users in New York City. From then on, gaslighting had its first really serious competitor. [149] Had a successful incandescent gaslighting device not been invented soon thereafter, it is quite possible that gaslight would have been almost entirely supplanted by electric light before the close of the century. However, gas was able to continue an increasingly futile rear guard action until about 1910 in domestic lighting and even a little longer in street lighting, thanks in large part to the Welsbach burner, or gas mantle. The Austrian chemist Dr. Carl Auer von Welsbach (1856-1929), who was raised to the rank of Baron by Emperor Franz Josef for his discoveries, developed his first incandescent gas mantle during the years 1885-1886. It consisted of a cotton mesh cylinder gathered at the top and treated with a solution of rare earth minerals (principally thorium dioxide with a touch of cerium oxide). After the cotton was burned off, the incombustible oxides formed an open cone that glowed with intense light when placed over a burner within a glass chimney. The early mantles were fragile, but in 1887, when the first factory for their manufacture was established, a life of from 800 to 2,000 hours was claimed for them. [150]

Contemporary accounts reported:

The electricians will have to wake up, if they do not wish to be left behind in one of their most important fields of labor. Within the last few days a new light has made its appearance in the City [of London] which rivals in brilliance the best they have yet produced. . . . Dr. Welsbach calls this his "mantle" . . . . The moment the flame is applied the mantle becomes incandescent, that is, rises to white heat, and gives out a brilliant, mellow light, which it may be said, without any exaggeration, will compare favourably with any electric light yet put on the market... [151]

The new incandescent gas light invented by Dr. Carl Auer von Welsbach, of Vienna, promises to confer a real boon upon all who use gas as an illuminant. The advantages claimed for this invention—and not only claimed, but proved by actual experiment—are manifold. . . . The new system has been proved both practically and commercially. It has been in use for some time in Vienna, Berlin, &c., and it is considered the greatest discovery made in gas lighting since gas was first introduced for illuminating purposes. [152]

The advertisement reproduced in facsimile on this plate was the first to appear for the Welsbach burner and was published in the Journal of Gas Lighting in London in December 1890. Note that the text boasted "Electric Light Surpassed." The "drawbacks" of electric light to which the advertisement referred were primarily the need for stringing wires and the fairly frequent power failures. The rapid spread of incandescent gaslight is indicated by the sales statistics for Great Britain: 20,000 Welsbach burners were sold in 1893, 105,000 in 1894, and 300,000 were sold in 1895. [153]

|

| Reprint from Chandelier, Outline of History of Lighting, Courtesy of American Gas Association, Inc. Library, Arlington, Virginia. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

myers/plate10.htm

Last Updated: 30-Nov-2007