MENU

Presidential Statement

Foreword

Preface

|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Part III: The Park Movement |

|

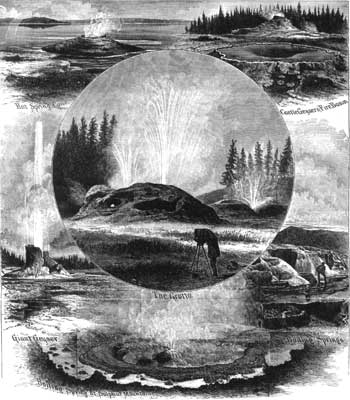

Yellowstone Geyers,

from Ferdinand Hayden's Geological Surveys of the Territories

(1872)

The Park Movement (continued)

Of greater importance, while the Yellowstone legislation was yet under consideration in Congress, was the effect of a number of popular and scientific articles which appeared in various publications. The artist with the Hayden Survey party in 1871, Henry W. Elliott, was also a field correspondent for Leslie's Illustrated, and he provided that magazine with a brief description of the Yellowstone region as he had seen it. [39] Captain Barlow, whose small party had accompanied Hayden's through the Yellowstone region in 1871, provided the Chicago Evening Journal with a detailed account, and later prepared an official report. [40] But it was geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden who was most influential in both the popular and scientific medium.

Hayden's article in Scribner's Monthly (written to accompany Thomas Moran"s sketches) reached a large and influential body of readers, to whom he brought this message: "Why will not Congress at once pass a law setting it [the Yellowstone region] apart as a great public park for all time to come, as has been done with that far inferior wonder, the Yosemite Valley?" [41] His scientific article, though written prior to the passage of the Yellowstone legislation, did not appear until later; [42] thus, the closing statement, another powerful call for reservation of the Yellowstone region as a national park, could have influenced only those who had seen Hayden's draft. Regardless, the title, "On the Yellowstone Park," is a measure of his considerable faith in the legislation then awaiting the action of the House of Representatives.

Before following the Yellowstone legislation to its conclusion, it is necessary to note a letter written to F. V. Hayden on February 19. In it, George A. Crofutt, author of a prominent tourist guidebook, expressed his indignation at the failure of a news item in the New York World of the previous day to give the geologist proper credit for the maturing park scheme. [43] Evidently, N. P. Langford had been identified as the king-pin of the movement, and not just by the World; similar releases have been found in the St. Joseph Herald (Missouri), and the Virginia Daily Territorial Enterprise (Nevada). [44]

While the Senate bill, S. 392, was making such splendid progress, its counterpart in the House, Delegate Clagett's H.R. 764, remained with the Committee on Public Lands, unreported for more than 2 months. During this time, the only action taken on the measure was a request from the chairman of the subcommittee to the Secretary of the Interior for a copy of Hayden's report. In his letter to Secretary Delano, January 27, 1872, Representative Mark H. Dunnell stated:

The Committee on Public Lands has under consideration the Bill to set apart some land for a Park in Wyoming T. As Ch. of a subcommittee on the bill, I will be pleased to receive the report made by Prof. Hayden or such report as he may be able to give us on the subject. [45]

Dunnell"s request reached the Secretary on the 29th and was answered by him the same day. [46] His reply not only provided the desired information in the form of a brief special report prepared by Hayden, but also included this comment: "I fully concur in his recommendations, and trust that the bill referred to may speedily become a law."

Hayden's full report was in draft at that time, for Capt. John Barlow had mentioned seeing and approving it earlier; [47] however, it was not suited to the purpose at hand and a synopsis was substituted. This document was held by the House Committee on Public Lands for nearly a month without further action; in the vernacular, they "sat upon it."

Meanwhile, the bill which had passed the Senate—Pomeroy's S. 392— went over to the House and was brought up on February 27 in the regular order of business. Immediately upon its introduction, the following exchange took place: [48]

Mr. SCOFIELD. I move that the bill be referred to the Committee on the Public Lands.

Mr. DAWES. I hope that bill will be put upon its passage at once. It seems to be a meritorious measure.

Mr. TAFFE. I move that it be referred to the Committee on the Territories.

Mr. SCOFIELD. At the request of the gentleman from Massachusetts [Rep. Dawes], I withdraw my motion.

Mr. HAWLEY. This question was referred to the Committee on the Public Lands in a House bill exactly similar in all its respects to this bill; it was considered by that committee, and the gentleman having it in charge was instructed to report it favorably to the House, [49] and if the committee were on call it would be reported.

Mr. DUNNELL. I was instructed by the committee to ask the House to pass a bill precisely like the bill passed by the Senate. I have examined the question thoroughly and with a great deal of care, and I am satisfied that the bill ought to pass. [50]

Mr. DAWES. It seems very desirable that the bill should pass as early as possible, in order that the depredations in that country shall be stopped.

Mr. FINKELNBURG. I would like to have the bill read.

The bill was read. [The text of the bill, as amended by the Senate, was given in full.]

Mr. DAWES. This bill follows the analogy of the bill passed by Congress six or eight years ago, setting apart the Yosemite valley and the "big tree country" for the public park, with this difference: that that bill granted to the State of California the jurisdiction over that land beyond the control of the United States. This bill reserves the control over the land, and preserves the control over it to the United States, [51] so that at any time when it shall appear that it will be better to devote it to any other purpose it will be perfectly within the control of the United States to do it.

It is a region of country seven thousand feet above the level of the sea, where there is frost every month of the year, and where nobody can dwell upon it for the purpose of agriculture, containing the most sublime scenery in the United States excepting the Yosemite valley, and the most wonderful geysers ever found in the country. [52]

The purpose of this bill is to preserve that country from depredations, but to put it where if the United States deems it best to appropriate it to some other use it can be used for that purpose. It is rocky, mountainous, full of gorges, and, from the descriptions given by those who visited it during the last summer, is unfit for agricultural purposes; but if upon a more minute survey it shall be found that it can be made useful for settlers, and not depredators, it will be perfectly proper this bill should pass; it will infringe upon no vested rights, the title to it will still remain in the United States, different from the ease of the Yosemite valley, where it now requires the coordinate legislative action of Congress and the State of California to interfere with the title. [53] This bill treads upon no rights of the settler, infringes upon no permanent prospect of settlement of that Territory, and it receives the urgent and ardent support of the Legislature of the Territory, and of the Delegate himself, who is unfortunately now absent, and of those who surveyed it and brought the attention of the country to its remarkable and wonderful features. We part with no control ; we put no obstacle in the way of any other disposition of it; we but interfere with what is represented as the exposure of that country to those who are attracted by the wonderful descriptions of it by the reports of the geologists, and who are going there to plunder this wonderful manifestation of nature.

Mr. TAFFE. I desire to ask the gentleman a question, and it is whether this measures does not interfere with the Sioux reservation and in the next place I know that that treaty, if you call it a treaty, which I never thought it was, because the law raising the commission said the treaty should be ratified by Congress and not by the Senate, and under that you abandoned the right to go into the country between the Missouri river and the Big Horn mountain. Now, I ask the gentleman if this bill does not infringe upon the territory set apart for these Indian tribes?

Mr. DAWES. The gentleman has my answer, because he has heard it a great many times here. Both Houses have acted upon the theory that all of the treaties made by this commission are simple matters of legislation.

Mr. TAFFE. That does not answer my question as to the right of settlers to go upon this land. If that is not included in the treaty, then settlers have a right to go upon that land to-day; if that is the treaty, then nobody has a right to go into the country between the Big Horn mountain and the Missouri river except with the consent of these Indian tribes. [54]

Mr. DAWES. That may be; but the Indians can no more live there than they can upon the precipitous sides of the Yosemite valley.

Mr. SCOFIELD. I call the previous question.

The previous question was seconded and the main question ordered, which was upon the third reading of the bill.

Mr. STEVENSON. I ask leave to have printed in the Globe some remarks upon this bill.

No objection was made; and leave was accordingly granted. [See Appendix] [55]

The question was upon ordering the bill to be read a third time; and upon a division there were—ayes 81, noes 41.

So the bill was ordered to be read a third time; and it was accordingly read the third time.

The question was upon the passage of the bill.

Mr. MORGAN. Upon that question I call for the yeas and nays.

The question was taken upon ordering the yeas and nays; and there were twenty-seven in the affirmative.

So (the affirmative being one fifth of the last vote) the yeas and nays were ordered.

The question was then taken; and it was decided in the affirmative— yeas 115, nays 65, not voting 60; as follows:

YEAS—Messrs. Ames, Archer, Averill, Banks, Barber, Barry, Beatty, Beveridge, Bigby, Biggs, Bingham, Austin Blair, Boles, George M. Brooks, Buckley, Buffiington, Burchard, Burdett, Roderick R. Butler, William T. Clarke, Cobb, Coburn, Conger, Cotton, Cox, Crebs, Crocker, Darrall, Dawes, Dickey, Donnan, Duell, Dunnell, Eames, Farnsworth, Farwell, Wilder D. Foster, Frye, Garfield, Hale, Hambleton, Harmer, George E. Harris, Havens, Hawley, Hays, Gerry W. Hazelton, John W. Hazelton, Hereford, Hill, Hoar, Hooper, Houghton, Kelley, Kellogg, Kendall, Ketcham, Lamport, Leach, Maynard, McCrary, McGrew, McHenry, McJunkin, McNeely, Mercur, Merriam, Mitchell, Monroe, Leonard Myers, Negley, Orr, Packard, Packer, Palmer, Peck, Pendleton, Aaron F. Perry, Peters, Potter, Ellis H. Roberts, Rusk, Sargent, Sawyer, Scofield, Seeley, Sessions, Sheldon, Shellabarger, Sherwood, Shoemaker, Sloss, H. Boardman Smith, John A. Smith, Snapp, Snyder, Sprague, Stevens, Stevenson, Stoughton, Swann, Washington Townsend, Turner, Tuthill, Twichell, Upson, Wakeman, Waldron, Wallace, Wheeler, Willard, Williams of New York, Jeremiah M. Wilson, John T. Wilson, and Wood— 115.

NAYS—Messrs. Acker, Arthur, Barnum, Beck, Bird, Braxton, Caldwell, Coghlan, Comingo, Conner, Critcher, Crossland, DuBose, Duke, Eldredge, Finkelnburg, Forker, Henry D. Foster, Garrett, Getz, Golladay, Griffith, Haldeman, Handley, Hanks, John T. Harris, Hay, Herndon, Hibbard, Holman, Kerr, Killinger, Lewis, Lowe, Manson, McClelland, McCormick, McIntyre, Benjamin F. Meyers, Morgan, Niblack, Eli Perry, Price, Prindle, Rainey, Read, Edward Y. Rice, John M. Rice, William R. Roberts, Shanks, Slater, Slocum, R. Milton Speer, Thomas J. Speer, Starkweather, Strong, Taffe, Terry, Tyner, Van Trump, Voorhees, Waddell, Whitthorne, Winchester, and Young—65.

NOT VOTING—Messrs. Adams, Ambler, Bell, James G. Blair, Bright, James Brooks, Benjamin F. Butler, Campbell, Carroll, Freeman Clarke, Creely, Davis, De Large, Dox, Elliott, Ely, Charles Foster, Goodrich, Halsey, Hancock, Harper, King, Kinsetta, Lamison, Lansing, Lynch, Marshall, McKee, McKinney, Merrick, Moore Morey, Morphis, Hosea W. Parker, Isaac C. Parker, Peree, Platt, Poland, Porter, Randall, Ritchie, Robinson, Rogers, Roosevelt, Shober, Worthington C. Smith, Storm, Stowell, St. John, Sutherland, Sypher, Thomas, Dwight Townsend, Vaughan, Walden, Walls, Warren, Wells, Whiteley, and Williams of Indiana—60.

So the bill was passed. [56]

Mr DAWES moved to reconsider the vote by which the bill was passed; and also moved that the motion to reconsider be laid on the table.

The latter motion was agreed to.

The enrolled bill was signed by the Speaker of the House on the following day, and, though it had yet to be approved by the President,the success of the measure was widely noted. The St. Louis Times (Missouri), and the Denver Daily Rocky Mountain News (Colorado), provided telegraphic notices that the "Yellowstone Valley" in Wyoming and Montana had been set apart, as a "national park" or a "public park," but only Montana s Helena Daily Herald had any serious comment to offer so soon. In its front-page article, this proponent of the park movement stated: [57]

Our dispatches announce the passage in the House of the Senate bill setting apart the Upper Yellowstone Valley for the purposes of a National Park. The importance to Montana of this Congressional enactment cannot be too highly estimated. It will redound to the untold good of this Territory, inasmuch as a measure of this character is well calculated to direct the world's attention to a very important section of country that to the present time has passed largely unnoticed. It will be the means of centering on Montana the attention of thousands heretofore comparatively uninformed of a Territory abounding in such resources of mines and of agriculture and of wonderland as we can boast, spread everywhere about us. The efficacy to this people of having in Congress a Delegate able, active, zealous and untiring in his labors, as well as in political harmony with the General Government, [58] is being amply demonstrated in the success attending the representative stewardship of Mr. Clagett. Our Delegate, surely is performing deeds in the interest of his constituents which none of them can gainsay or overlook, and those deeds are being recorded to his credit in the public's great ledger and in the hearts of us all.

On the following day, the New York Times commented in a broader vein, and without the partisan tootling:

It is a satisfaction to know that the Yellowstone Park bill has passed the House. Our readers have been made well acquainted with the beautiful and astonishing features of a region unlike any other in the world; and will approve the policy by which, while the title is still vested in the United States, provision has been made to retain it perpetually for the nation. The Yosemite Valley was similarly appropriated to public use some years back, and that magnificent spot was thus saved from possible defacement or other unseemly treatment that might have attended its remaining in private hands. . . . The new National Park lies in two Territories, Montana and Wyoming, but the jurisdiction of the soil, by the passage of the bill, remains forever with the Federal Government. In this respect the position of the Yellowstone Park differs from that of the Yosemite; since the latter was granted by Government to the State of California on certain conditions one of which excludes the local control of the United States; while the former will always be within that control.

Perhaps, no scenery in the world surpasses for sublimity that of the Yellowstone Valley; and certainly no region anywhere is so rich, in the same space, in wonderful natural curiosities. In addition to this, from the height of the land, and the salubrity of the atmosphere, physicians are of opinion that the Yellowstone Park will become a valuable resort for certain classes of invalids; and in all probability it will soon appear that the mineral springs, with which the place abounds, possess various curative powers. It is far from unlikely that the park may become in a few years the Baden or Homburg of America, and that strangers may flock thither from all parts of the world to drink the waters, and gaze on picturesque splendors only to be seen in the heart of the American Continent. [59]

The Yellowstone Park Act had the approval of President Ulysses S. Grant, who signed it into law on March 1, 1872. [60] The text of the act follows:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

That the tract of land in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming lying near the head-waters of the Yellowstone River, and described as follows, to wit, commencing at the junction of Gardiner's River with the Yellowstone River, and running east to the meridian passing ten miles to the eastward of the most eastern point of—Yellowstone lake; thence south along said meridian to the parallel of latitude passing ten miles south of the most southern point of Yellowstone Lake; thence west along said parallel to the meridian passing fifteen miles west of the most western point of Madison Lake; thence north along said meridian to the latitude of the junction of the Yellowstone and Gardiner's Rivers; thence east to the place of beginning is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people; and all persons who shall locate or settle upon or occupy the same, or any part thereof, except as hereinafter provided, shall be considered trespassers, and removed therefrom.

SEC. 2. That said public park shall be tinder the exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior, whose duty it shall be, as soon as practicable, to make and publish such rules and regulations as he may deem necessary or proper for the care and management of the same. Such regulations shall provide for the preservation, from injury or spoliation, or all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition. The Secretary may, in his discretion, grant leases for building purposes for terms not exceeding ten years, of small parcels of ground, at such places in said park as shall require the erection of buildings for the accommodation of visitors; all of the proceeds of said leases, and all other revenues that may be derived from any source connected with said park, to be expended under his direction in the management of the same, and the construction of roads and bridle-paths therein. He shall provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit. He shall also cause all persons trespassing upon the same after the passage of this act to be removed therefrom, and generally shall be authorized to take all such measures as shall be necessary or proper to fully carry out the objects and purposes of this act. [61]

The new park was received with mixed emotions in Montana. Helena's Rocky Mountain Gazette, which had previously expressed a fear that the park legislation would remand the Yellowstone region into "perpetual solitude," stated:

In our opinion, the effect of this measure will be to keep the country a wilderness, and shut out, for many years, the travel that would seek that curious region if good roads were opened through it and hotels built therein. We regard the passage of the act as a great blow struck at the prosperity of the towns of Bozeman and Virginia City, which might naturally look for considerable travel to this section, if it were thrown open to a curious but comfort-loving public. [62]

The sarcastic reply of the Herald turned the controversy into a political mud-slinging contest, with the only sensible comments coming from other newspapers. The Bozeman Avant Courier sided with the Gazette in the matter of the settler's interests in the new park, stating, in regard to the setting aside of the area, "we were certainly under the impression that, in ease such was done, ample provision would be made in the bill for opening up the country by making good roads and establishment of hotels and other accomodations," adding, "unless some such provisions are yet incorporated in the bill by amendment, we agree with the Gazette, that it would have been better to have left its development open to the enterprising pioneers, who had already commenced the work." [63]

The Deer Lodge New North-West preferred to remain on neutral ground, reminding the contending editors that, as the settlers upon park lands were really residents of Wyoming Territory, "we are unable to see how it [reservation] will damage citizens of this Territory." Attention was also called to another largely overlooked fact: that regardless of the act setting aside the Yellowstone region, such settlers "are of course trespassers against the General Government, as all persons who reside upon unsurveyed public lands not mineral." [64]

A more enlightened view of the accomplishment in setting aside the Yellowstone region "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" came from an eastern magazine, which noted:

It is the general principle which is chiefly commendable in the act of Congress setting aside the Yellowstone region as a national park. It will help confirm the national possession of the Yo Semite, and may in time lead us to rescue Niagara from its present degrading surroundings. That the park will not very soon be accessible to the public needs no demonstration. [65]

Those words foretold both the greatness of Yellowstone National Park, as the pilot model for a system of Federal parks, and the travail of its early years. At the moment, Americans were pleased with their new playground, and a few were also undismayed at its remoteness. Even as the organic act was being signed into law, the first visitors of that throng which swelled to more than 48 million persons in the first century were outfitting at the town of Bozeman for their park trip. [66] As a nation, we had come to realize a very important fact, which the New York Herald expressed this way:

Why should we go to Switzerland to see mountains, or to Iceland for geysers? Thirty years ago the attraction of America to the foreign mind was Niagara Falls. Now we have attractions which diminish Niagara into an ordinary exhibition. The Yo Semite, which the nation has made a park, the Rocky mountains and their singular parks, the canyons of the Colorado, the Dalles of the Columbia, the giant trees, the lake country of Minnesota, the country of the Yellowstone, with their beauty, their splendor, their extraordinary and sometimes terrible manifestations of nature, form a series of attractions possessed by no other nation in the world. [67]

End of Part III

Top

Last Modified: Tues, Jul 4 2000 07:08:48 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/haines1/iee3c.htm

![]()