|

Grand Teton National Park |

|

|

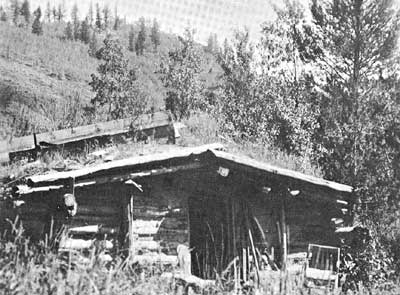

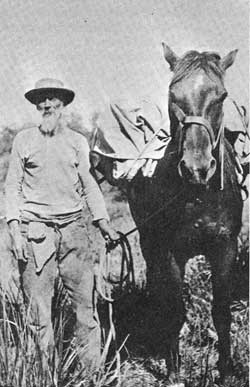

PROSPECTOR OF JACKSON HOLE1 In the 1880's and 1890's it was widely supposed that the Snake River gravels of Jackson Hole, in Wyoming, contained workable deposits of placer gold, and there were many who came to the region, lured by such reports and a prospector's eternal optimism. Color, indeed, could be struck almost anywhere along the river, but the gold of which it gave promise proved discouragingly scarce and elusive. None found what in fairness to the word could be called a fortune. Few found sufficient gold to maintain for any length of time even the most frugal living—and who can live more frugally than the itinerant prospector? So through these decades prospectors quietly came and sooner or later as quietly left, leaving no traces of their visit more substantial than the scattered prospect holes still to be seen along the bars of the Snake River. Even today a prospector occasionally finds his way into the valley, and, like a ghost out of the past, may be seen on some river bar, patiently panning. Probably he, too, will drift on. It is apparent now that the wealth of Jackson Hole lies not in gold-bearing gravels but in the matchless beauty of its snow-covered hills and the tonic qualities of its mountain air and streams. But one prospector stayed. Mysterious in life, Uncle Jack Davis has become one of the most shadowy figures in the past of Jackson Hole, little more than a name except to those few still left of an older generation who knew him. He deserves to be remembered—deserves it because of his singular story, and because he has the distinction historically of having been the only confirmed prospector in Jackson Hole. He was "Uncle" only by courtesy for he lived a lonely hermit until his death; and so far as is known he left no relatives. He first appeared in 1887 as one of the throng of miners drawn irresistibly into that maelstrom of the gold excitements, Virginia City, Montana. In a Virginia City saloon he became involved in a brawl and struck a man down, struck him too hard and killed him. Davis, it should be remarked, was a man of herculean strength and, at the time of this accident, he was drunk. Believing himself slated for the usual treatment prescribed by Montana justice at the time—quick trial and hanging—he fled the city. Davis reappeared shortly after this in Jackson Hole, the resort of more than one man with a past, and in the most isolated corner of that isolated region he began life anew. At the south end of the Hole, a few miles down the Grand Canyon, he took out a claim on the south side of the Snake River near a little tributary known as Bailey Creek. There he built a log cabin, the humblest structure imaginable—one room, no windows, a single door hung on rawhide hinges. This primitive shack was Jack Davis' home for nearly a quarter of a century. True, more than two decades later he built himself a new cabin, but death knocked at the door of the old one before he could move.

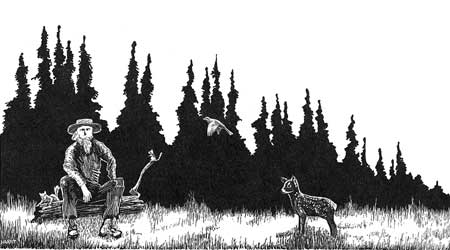

Down in the bottom of this magnificent canyon which he had almost to himself, Davis plied his old trade of placer mining, putting in the usual crude system of sluice boxes and ditches. In addition, he cultivated a patch of ground which yielded vegetables sufficient for his own needs and for an occasional trade. The income from both sources was ridiculously small, but his needs were modest enough. Primarily he wished peace and seclusion, and these he found. The Virginia City episode never ceased to trouble him. It made him a recluse for life. He lived alone, and limited his associates almost entirely to the few neighbors who, as the years passed, came to share his canyon or that of the nearby Hoback River. Trips to town were made only when necessary, and were brief. On such occasions it was his practice to cross the Snake near his cabin and hike or snowshoe up the west side to the store at Menor's Ferry, 50 miles distant. Having made his purchases he shouldered them and returned by the same route. In the course of his journey he saw and talked to few. He rarely went to Jackson, the only town in the region. He is said to have been a sober man, afraid of drink. Davis' solitary habits sprang from a haunting fear of pursuit, not from dislike of companionship. The presence of a stranger in the region made him uneasy, and he did not rest until his mission was known, sometimes pressing a friend into service to ascertain a stranger's business. He rarely allowed his photograph to be taken. Apparently his fears had little foundation, for no one from "outside" ever came in after him. Very likely Virginia City soon forgot him. Davis' past was known to only 1 or 2 of the most intimate of his neighbors. They kept it to themselves. Nor would it have mattered had this story been more generally known—not in Jackson Hole where such a distinction was by no means unique, and where a man was judged for what he was, not for what he had been, or had done. Though a strange recluse, he was a man to be admired and respected. Physically he was tall, broad, of magnificently erect carriage—a blue-eyed, full-bearded giant. Stories of his strength still enjoy currency. According to one of these, Uncle Jack once lifted a casting which on its shipping bill was credited with weighing 900 pounds—lifted it by slipping a loop of rope under it, passing the loop over his shoulders, and straightening his back. And it was well known that for all his solitary habits, Uncle Jack was kind and generous as he was strong. It seems as though for the remainder of his days Uncle Jack did penance for his one great mistake. He impressed one as trying hard to do the right thing by everyone and everything. Such was his love for birds and animals that he would go hungry rather than shoot them. To callers at his shack he explained the absence of meat from the table by a stock alibi so lame and transparent that it fooled no one: "He'd eat so much meat lately that he'd decided to lay off it for awhile." His unwillingness to kill turned him into a vegetarian—here in the midst of the best hunting country in America. A hermit, yet Uncle Jack was hardly lonely. In birds and beasts of the canyon he found a substitute for human companionship. The wild creatures about him soon ceased to be wild. His family of pets included Lucy, a doe who lived with him for many years; Buster, her fawn, whom the coyotes finally killed; two cats—Pitchfork Tillman, named for a prominent political figure of the times, and Nick Wilson, much given to night life, so named after a prominent pioneer of the valley; and a number of tame squirrels and bluebirds. Not to mention Dan, the old horse, and Calamity Jane, the inevitable prospector's burro, which had accompanied Jack in his flight to Jackson Hole, where it finally died at the advanced age of 40 years. Maintaining peace in such a family kept Uncle Jack from becoming lonely.

Al Austin, who for many years was forest ranger in this region, and who in time came to enjoy Uncle Jack's closest confidence, presents an unforgetable picture of the old man and his family. Dropping in at mealtime for a friendly call, Austin would find Uncle Jack in his cabin surrounded by his pets, each clamouring to be fed and each jealous of attention bestowed on any creature other than itself. If the bluebirds were favored, the squirrels chattered vociferously. Buster, if irritated, would justify his name by charging and upsetting the furniture. Add to this the audible impatience of Pitchfork Tillman and Nick Wilson, Lucy was ladylike but nevertheless insistent. To this motley circle Uncle Jack would hold forth in inimitable language, carrying on a running stream of conservation—scolding, lecturing, admonishing, or when discord became acute, threatening dire punishment if they did not mend their ways. It is hardly necessary to add that to Uncle Jack's awful threats, and the vivid profanity, which it must be admitted, accompanied them, the members of the household remained serenely indifferent, and there is no record that any of the promised disasters ever fell on their furry heads. Having no windows, Uncle Jack left his door open during the good weather. One spring a pair of bluebirds flew through the open door into the shack and, having inspected the place and found it to their liking, built their nest behind a triangular fragment of mirror which Uncle Jack had stuck on the wall. Uncle Jack then cut down the door from its leather hinges and did not replace it until fall. Six successive summers the bluebirds returned to the cabin, and, finding the door removed in anticipation of their coming, built their nest and raised their young behind Uncle Jack's mirror. Nearby Uncle Jack made a little graveyard for his pets, as they left him one by one. It was lovingly cared for. In the course of the 24 years which he spent there the burial ground came to contain many neat mounds—mounds of strangely different sizes. But Lucy, Pitchfork Tillman, and Dan outlived Uncle Jack. He would not accept charity, even during the last year or two of his life when he was nearly destitute. Neighbors had to resort to strategy to get him to accept help. On his periodic trips up and down the canyon, Austin brought the mail to Davis and to Johnny Counts, who lived next to the north. Counts and Davis, too, occasionally exchanged visits. On March 14, 1911, Austin called at Counts' and, finding that nothing had been heard of from Uncle Jack for some time, snowshoed on down the canyon to see if all was well. The old man lay in bed, delirious. The last date checked off on the wall calendar was February 11. Outside the cabin, elk had eaten all the hay, and the horse and Lucy were at the point of starvation. Austin stayed by his bedside for several days, then, finding it impossible to care for Uncle Jack decently in the dark old cabin, summoned Counts. Several days later they moved the old man 6 miles up the river, carrying him where they could, most of the way pulling him along in a boat from the shore. The old trail was one Jack himself had built many years before. In Count's cabin, a week later, Uncle Jack died. Austin made Uncle Jack's coffin from one of the old man's own sluice boxes. Together the two men carried Uncle Jack to the grave they had dug for him at Sulphur Springs, nearby in the canyon. A wooden headboard on which Ranger Austin carved the inscription, "A. L. Davis, Died March 25, 1911," marks the grave—there Uncle Jack sleeps alone. In Davis' shack was found the "fortune" which placer mining had brought him—$12 in cash and about the same value in gold amalgam. 1 Reprinted from American Forests, October 1935, with the permission of the author and editor of American Forests. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole ©1960, Grant Teton Natural History Association campfire_tales/chap6.htm — 27-Mar-2004 | ||