|

Grand Teton National Park |

|

|

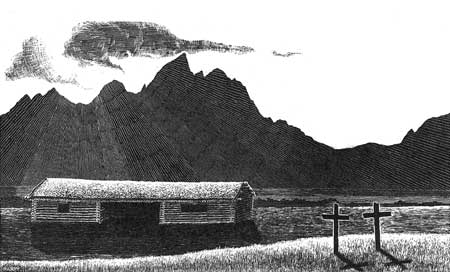

THE AFFAIR AT CUNNINGHAM'S RANCH1 Close against the Idaho-Wyoming border, at the headwaters of the Snake River, lies the high, mountain-girt valley of Jackson Hole. Fiercely beautiful in setting and richly historic in background, Jackson Hole and the raw, jagged peaks of the Teton mountains to the west have captured popular imagination as has no other region in the Rockies. Jackson Hole has become a fabled out-post of the vanished Western frontier, the legendary "last stand of the outlaws." And of all the stories which have given rise to that picture, perhaps none is more starkly simple than one which has become known as The Affair at Cunningham's Ranch. As in the case of other frontier communities, the story of the early settlers in Jackson Hole is one of isolation and hardship. When winter closed in and cut off the valley from the nearest settlements across the mountains, life was a struggle for survival against the bitter cold and drifting snow. Occupied with the task of making a home in the face of tremendous odds, the homesteaders were solid, law-abiding citizens with little time for lawlessness, and less for violence. On the rare occasions when gun-play broke out between men in the valley, it was of a nature that could hardly appear heroic except through the romantic eyes of a novelist. In the harsh light of reality, violence was brutal and ugly, and dispatched with a speed and finality grimly typical of the frontier. The Cunningham Ranch affair broke with a suddenness that shocked the entire valley. It was as cold-blooded as it was simple. A posse came riding in from Montana in the spring of 1893, and at a little cabin near Spread Creek two men were cornered and shot for horse-stealing. Little news of the Spread Creek incident ever leaked out of the valley in the early days, and when the first general flow of tourist travel into Jackson Hole began nearly 40 years later, the affair at Cunningham's Ranch was still a widely known but reticently guarded story. By then most of the old-timers who had been members of the posse were dead, and those who were left still were not interested in discussing the matter. And so the story of the killing relies almost entirely on the memory and information of the one man who cared to talk about it, Pierce Cunningham. A quiet, weather-beaten little man, Pierce Cunningham came into Jackson Hole with the first influx of settlers during the late 1880's and early 1890's. He homesteaded in the valley, and there, on Flat Creek, he worked his ranch and married and raised his family. In the fall of 1892, while he was haying on Flat Creek, Cunningham was approached by a neighbor named White who introduced 2 strangers, stating that they wished to buy hay for a bunch of horses they had with them. One of the men, named George Spenser, was about 30 and had come originally from Illinois; the other was an Oregon boy named Mike Burnett, much younger than Spenser but already rated a first-class cattleman after having punched cattle for several years elsewhere in Wyoming. Cunningham sold them about 15 tons of hay and incidentally arranged to let the men winter in his cabin near Spread Creek, about 25 miles to the north. Since Cunningham himself intended to remain at Flat Creek, he also arranged for his partner, a burly Swede named Jackson, to stay with them. Rumor began spreading during the winter that the 2 men on Cunningham's place were fugitive horse thieves. Some of the rustlers' horses, it was said, belonged to a cattleman in Montana; a valley rancher had worked for him and recognized some of the brands. Before the snow was gone Cunningham had taken it upon himself to snowshoe to Spread Creek, investigate conditions, and warn Jackson to be on guard. Once there his suspicions were confirmed. Cunningham spent several days with the men, went with them to search for their horses, and recognized certain stocks and changed brands that left no question in his mind as to their guilt. The die was cast, and although he could readily have warned the men of their danger, Cunningham returned home without doing so. The next spring, however, he ordered Spenser and Burnett to leave, and they did but unfortunately for them, they returned to look for some horses on the very day they should have been absent. This was in April 1893. Across the mountains to the west a man from Montana was organizing a posse in the little Idaho settlement of Driggs. Somehow, possibly on a tip relayed from the Hole, he had got wind of the rustlers on Cunningham's place and was coming to get them. One of the valley homesteaders saw the posse leader there with a group of 15 men on saddle horses, and a few days later they came riding over the pass from Teton Basin into Jackson Hole. In the valley of the leader completed organization of the posse. Including him, there were 4 men from Montana, 2 from Idaho, and 10 or 12 recruited in Jackson Hole. Asked to join the outfit, Cunningham refused, and stayed at Flat Creek. The posse elected a spokesman, and then started up the valley to the Spread Creek cabin—a group of 16 men, all mounted and heavily armed. Under cover of darkness, the posse approached the cabin, a low, sod-roofed log building in dark silhouette against the night sky. Silently they surrounded it; 6 men in the shed about 150 yards northwest of the cabin, 3 took cover behind the ridge about the same distance south of the cabin, and the rest presumably scattered at intermediate vantage points. And then they waited for dawn.

Inside the cabin the unsuspecting men were sleeping quietly: Spenser, the older man, sandy-haired and heavily built; Burnett, the cowpuncher, slender and dark; and of course Swede Jackson, Cunningham's partner. The two rustlers intended to leave when it got light. Early in the morning the dog which was in the cabin with the men began to bark shrilly, perhaps taking alarm at the scent of the posse. Spenser got up, dressed, buckled on his revolver, and went out to the corral. The corral lay between the cabin and the shed, and after Spenser had entered it one of the posse called to him to "throw 'em up." Instead Spenser drew with lightning speed and fired twice, one bullet passing between two logs and almost hitting the spokesman, the other nicking a log near by. The posse returned fire and Spenser fell to the ground, propping himself up on one elbow and continuing to shoot until he collapsed. Meanwhile Burnett had got up, slipped on his overalls and boots, and fastened on his revolver. Then he picked up his rifle in his right hand and came out of the cabin. As he stepped forth, one of the men behind the ridge fired at him. The bullet struck the point of a log next to the door, just in front of Burnett's eyes. Burnett swept the splinters from his face with his right hand as he reached for his revolver with his left, and fired lefthanded at the top of the gunman's hat, just visible over the ridge. The shot was perfect; the bullet tore away the hat and creased the man's scalp. He toppled over backwards. Burnett then deliberately walked over to the corner of the cabin and stopped, with rifle in hand, in full view of the entire posse, taunting them to come out and show themselves. From inside the cabin Jackson pleaded with him to come in or he would get it too. Burnett finally turned, and as he did so one of the members of the posse shot him. The bullet killed Burnett instantly, and he pitched forward toward the cabin, discharging his rifle as he fell. Now only Jackson was left in the cabin. A big, bumbling man with a knack for trouble, Jackson had once before been taken by mistake for a horsethief and been scared almost to death; when he was now ordered to come out and surrender with his hands in the air he did so immediately. The work of the posse was done. Mike Burnett lay face down in the dirt at the corner of the cabin, the bullet from his last shot lodged in a log beside him; George Spenser, his six-shooter empty, was sprawled inside the corral with 4 charges of buckshot and 4 or 5 bullets in his body. They were buried in unmarked graves a few hundred yards southeast of the cabin, on the south side of a draw. No investigation was ever made, no trial held, and the matter was hushed up. As years went by the subject of the killing at Spread Creek became a touchy one, and most of the men directly involved preferred not to talk about it. Swede Jackson, apparently thoroughly shaken by the incident, left the valley and did not return. The affair at Cunningham's Ranch was a closed story. What information the members of the posse did volunteer in later years was in justification of their actions. The posse leader was a Montana sheriff, they said, and he and his men had come from Evanston, Wyoming, with the "proper papers," and deputized the Jackson Hole men. According to them there had been no intention of killing—the 2 victims had been given a chance to surrender, and after the affair one of the men in the posse had gone to Evanston to report it to the police. Those in the valley who had not been in on the posse were not so sure of the legality of the shooting. Cunningham said he thought the leader was not an officer, and reiterated that the posse had been instructed not to arrest but to kill. He stated that 2 local men had previously been asked to dispose of the pair, but had refused. When asked who raised the posse and investigated the killing, Cunningham laughed and said he could tell but preferred not to; asked if he cared to state whether the move was local or not, he quickly said, "Oh no—it wasn't only local." Cunningham himself was rumored to have warned the outlaws to be on guard, having returned from the Spread Creek ranch only a short time before the killing. The story easily gained credence, since Spenser had caught the posse completely by surprise when he armed himself and started directly for the corral and shed where the men were hidden. Cunningham denied "tipping them off," and Jackson later said it was unusual for the dog to bark as it did that morning. Spenser probably sensed from the dog's actions that something was amiss and so put on his gun before leaving the cabin, a precaution which Jackson said the men had never taken during the previous winter. Cunningham seemed more favorably impressed by the behavior of the 2 horsethieves than by any heroism on the part of the posse, an attitude which was general in the valley. Members of the posse had little to say about it. In 1928, several years before his death, Pierce Cunningham recounted the story of the killing at Spread Creek and ended by pointing out the spot where the rustlers were buried. With 2 timbers he marked the sage-covered plot, one corner of it crossed by the road then running past the cabin, where George Spenser and Mike Burnett had lain since their death in 1893. Years later badgers threw out some of their bones into the sunlight. 1 Reprinted from Saga, literary magazine of Augustana College, 1955 with permission of the author and the editor of Saga. This narrative is based on detailed historical notes obtained by the author's father, Fritiof Fryxell, more than 30 years ago, in conversation with early settlers of Jackson Hole—including Pierre Cunningham himself—who were in a position to furnish reliable information concerning The Affair at Cunningham's Ranch. In the recording of these notes, and their use in preparing the present account, every effort was made to reconstruct as accurately as possible, except that the names of the posse were purposely omitted. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole ©1960, Grant Teton Natural History Association campfire_tales/chap5.htm — 27-Mar-2004 | ||