|

Man in Glacier

|

|

|

Chapter Six: GUARDIANS OF GLACIER

In September of 1971, fourteen Park Service trail crewmen set aside their tools, picked up their pens, and initiated a protest concerning the construction of a boardwalk on a trail near the Logan Pass Visitor Center. They considered the walkway of chemically treated lumber to be an environmental "atrocity." Their protest letter was published in the local newspaper, and the following workday these seasonal employees were "terminated" due to "weather conditions" and "lack of supplies and materials to continue the job." Responding to the public fury which followed the trail crew dismissal, Superintendent William J. Briggle substantiated his administrative purpose, remained critical of the recalcitrant employees' methods, but finally stated that "these men will be considered for re-employment next summer." The actions of park employees who had been hired to carry out construction and the park administrators who initiated the controversial project stemmed from the same objective: the ideal of protecting and preserving Glacier National Park. To the trail crew, it seemed like an "atrocity" to add a huge wooden boardwalk through a practically virgin area. To park planners, the need to limit damage from an estimated four hundred hikers per hour through the area during the summer months seemed to warrant this construction. Both administrators and employees expressed a concern for the preservation of Glacier's wilderness characteristics, but they disagreed over the method of achieving that goal.

For the first time in Glacier's history, Park Service employees actively protested and placed their ideals over their personal welfare to publicize what they considered an extraneous and unsightly project. No one had earlier protested when Many Glacier Hotel was built; no one blocked the construction of Going-to-the-Sun Road; the CCC boys gladly cut acres of Glacier's fire-killed trees. What had led to this attitude of environmental idealism and concern for Glacier's wilderness in the 1970s which appeared to be more intense than ever before? Would the idealism of an "environmental conscience" prevail or would the historic attitude that national parks could be "all things to all people" continue in Glacier? Part of the answer may be found in the three decades of activity following World War II. The decade of the forties began with an upswing in visitation to Glacier and a corresponding addition of "multiple use" facilities at Rose Creek (now Rising Sun) and Swiftcurrent. Any expectation that these facilities were excessive seemed to be negated. Superintendent Donald Libby felt that any and all Park Service proposals and programs "are in the public interest and are able to undergo public examination because of the beneficial understanding and support which will result." By 1940, expansion was also proposed for several of the park campgrounds, with electrical hookups to be provided for the newest innovation in camping trailers. Regarding one of these expansion proposals, several rangers advised the superintendent that Two Medicine "should never have been opened to camping in the first place" while arguing that its fragile vegetation and the constant threat of forest fires rendered the site unsuitable. The electrical installation idea was discarded as too "intrusive," but campground expansion at Two Medicine and elsewhere proceeded in accord with growing public demand. However, the onset of World War II curtailed the influx of visitors to the park. Many of the rangers took leave to enter the Armed Forces and the Park Service kept only the most essential entrance and ranger stations open by using a reduced staff. A small contingent of conscientious objectors supplemented the park work forces during these years. And visitation dropped during the war years from the 180,000 of 1941 to a virtual standstill in 1943 of just over 23,000 people. By 1943, most of the facilities catering to the motoring public were shut down; the Great Northern Empire Builder no longer stopped at East Glacier Park or West Glacier because of war shipping priorities; bus transportation was temporarily terminated; and George Noffsinger's Saddle Horse Company moved to end its contract. In 1944, visitation increased slightly but the war still commanded public attention and park facilities stood idle, with neither the Park Service nor the Great Northern encouraging people to vacation in Glacier. Historian Michael Ober reported that during the entire 1944 season, only two hikers sought shelter at Lake McDonald Lodge. This lack of use during four full seasons made the revaluation of facilities necessary. By 1944, the park officials agreed that the old St. Mary Chalets at the foot of St. Mary Lake were no longer necessary and they were destroyed. Similarly, by 1946, the chalets at Cut Bank and at Sun Point were regarded as "beyond repair" and an "eyesore" and plans were made to destroy both facilities. By 1949, their destruction was complete and the areas were "returned to a natural setting."

But this wartime inactivity contrasted sharply with the expanding visitation in the decade which followed the war. During 1947, visitation topped 300,000, and the pressure on increased park use began to disturb park officials. While the Hotel Company finally began to show profits, to report filled and even over-flowing facilities, park officials began to realize that the motoring public needed more accommodations such as picnic areas, campgrounds, hotels, stores, or motels. Superintendent Libby had foreseen the postwar demands and, in 1944, warned: "this Service will inevitably have to face the impact of visitor usage which will demand many other services and facilities, and concerning which this Service should crystalize its position and be abreast of the problems rather than attempt to solve individually pressure demands as they occur." But pressure for the most adverse use came from an unsuspected quarter—the Federal Government. As early as 1943, the Army Corps of Engineers announced plans for the construction of the Glacier View Dam. This dam was to be located on the North Fork of the Flathead River and was proposed to complement the future Hungry Horse Dam on the Flathead River's South Fork. A major controversy began when the Corps' engineers introduced plans showing a proposed reservoir with a potential of flooding some twenty thousand acres of Glacier National Park. Some of the North Fork meadowland including Lone Pine and Round Prairies, private ranches, campgrounds, ranger stations, and the site of Polebridge store (just across the North Fork from the Polebridge Ranger Station), all would have been inundated. Further, the level of Logging Lake would have been raised some fifty feet and the entire Lower Camas Creek drainage would have been obliterated.

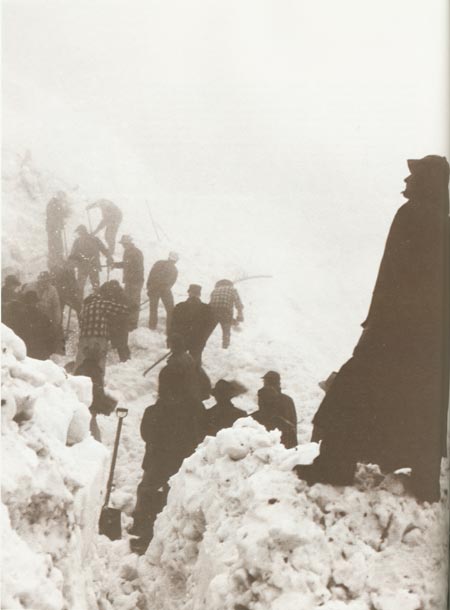

Beginning with the public disclosure of the plans and at the public hearings in 1948 and 1949, the Park Service officials confronted the Army Corps with an unalterable position opposing the dam construction. Superintendent J. W. Emmert argued that the public land of the park was "being used for the highest possible benefits to the public" and he would "object to any proposed extraneous development for purposes that would modify its primitive character." He added that the creation of a "fluctuating artifical body of water" would change the "wilderness character" of the area and be "detrimental to its cultural and inspirational values." Montana's Senator Mike Mansfield advocated the dam because it "would not disturb the economy but add to it," and he was joined by citizens' groups from nearby Martin City and the Flathead Valley. These local "boosters," labor unions, flood control advocates, and electric company backers, all felt the project to be of great economic importance for the development of the region. But Superintendent Emmert's fight for preservation gained a much wider support. Local residents from West Glacier and Lake McDonald (including the influential former Senator Burton K. Wheeler) as well as private landowners and ranchers in the North Fork region, voiced united opposition to the project. Senator Wheeler wrote: "I hope that the Park Service and the Interior Department will do everything they possibly can to prevent this dam from being built." One of forty landowners writing letters to protest the dam added: "To seriously curtail one of the few great recreational areas at a time when expansion, rather than decrease is needed, seems tragic." This local and Park Service opposition generated additional opposition to the dam. Both the Glacier Park Hotel and Transport Companies joined the various chambers of commerce in Montana opposing the Corps's proposal. Similarly, national conservation organizations like the Sierra Club, the National Audubon Society, the Society of American Foresters, and many others protested this "unwarranted invasion of Glacier National Park." The Army Corps of Engineers finally accepted the verdict against the Glacier View Dam site but continued to advocate other North Fork sites which would inundate less park land. Park Service officials kept a fearful eye toward the area and finally planned for greater "recreational" use of that wilderness area by building the "Camas Creek Road" to the North Fork River along the Apgar Mountains and by proposing several picnic areas and campgrounds in the region. This development, which some critics regarded as a "useless" highway, served as evidence of recreational intentions in the disputed area. Ironically, in 1967, a devastating forest fire swept through this controversial region and burned nearly all of the forest surrounding a proposed campground. Aside from the road, a bridge across the North Fork, and a seldom-used entrance station, little other recreational development resulted, but the dam-building project was effectively suspended. Another gambit Superintendent Emmert used in his arguments showing the "value" of Glacier was the display of increasing visitation to Glacier and the substantial economic benefit of that visitation to Montana's economy. By 1951, visitation had soared to over 500,000 visitors and the Park Service participated in a survey at the park entrances to determine the travel habits, "likes and dislikes," extent of their travel, and the amount of money expended by Glacier's visitors. The survey showed that the average park visitor spent five dollars per day during his two-day stay in the park and during his five-day stay in Montana. The economic impact of some 500,000 park visitors spending over $12,000,000 while in Montana gave park officials additional evidence to support their argument that recreational land was economically beneficial to the State. But, just as these growing numbers of visitors gave welcomed evidence of interest in the park, they proved a burden to Park Service and hotel facilities alike. Most other national parks were facing similar problems since "war-weary" Americans were "making up for lost time." Consequently, the increased post-war visitation to the outdated, deteriorated, or insufficient public accommodations became critical as automobile tourists multiplied. The New York Times quoted Park Service Director Newton B. Drury as saying that increasing pressure was being placed upon the Park Service to "break down their policies and standards." He felt that "economic need in some cases and sheer promotion in others had led to greater and greater demands for the cutting of forests, the grazing of meadows, the damming of streams and lakes and other destructive uses of the national parks." Drury later stated that due to increased park visitation, millions of dollars should be used to "modernize and expand" facilities "for entertaining visitors to the national parks." A local newspaperman, Mel Ruder, echoed Drury's statement and applied the national needs to Glacier. Ruder wrote in his Hungry Horse News: "Housing facilities both in and outside the park are inadequate. This also applies to campgrounds. Highway improvements have been too slow. Other park roads have been improved too little with resultant funnelling of visitors over the one 50-mile stretch of Sun highway." Regardless of the condition of park facilities, the economic significance of Glacier and its "Sun Road" attraction became more and more apparent. Local businessmen became anxious if the transmountain road was not cleared of snow "on schedule." The park concessionaires, local motel owners, restaurateurs, and gas station operators, all anticipated the summertime influx of tourists and their dollars once the road was opened. In June of 1953, Mel Ruder expressed concern over a late opening and stated: "With the Pass [Logan Pass] blocked, traffic to Glacier has been more than halved. The economic loss to Montana stores, cabin camps, service stations and restaurants runs into thousands of dollars." So the park officials dedicated substantial time, effort, and money to open the road each spring. Neither late snows, nor avalanche conditions, nor faulty equipment was permitted to delay the road crews. While some critics argued that this annual push was foolhardy and wasteful, the spring clearing project continued as a top priority. Unquestionably, this snow-removal project was extremely hazardous to the men employed to clear the snow. Merely locating a roadway covered by forty or fifty feet of snow presented problems. On several occasions snowslides pushed men and equipment off the road or covered them with snow. An example of this hazard occurred in May of 1953. That spring work had proceeded with the optimistic expectation that the road would be opened earlier than usual. However, a late, heavy, wet snow produced dangerous avalanche conditions. One snowslide nearly buried Jean Sullivan, the operator of a rotary snowplow, and his lookout Claude Tesmer.

Conditions worsened in the ensuing days and finally an entire crew of four men was hit by a devastating slide. In that avalanche Bill Whitford was thrown three hundred yards down the mountain and killed; George Beaton was buried and died; Fred Klien was badly injured; and Jean Sullivan was also buried, but miraculously located after seven and a half hours of searching. He had survived. His savior, Dimon Apgar, was sitting in West Glacier when he heard of the disaster. Apgar raced to the site, joined the search team and finally located Sullivan buried in the initial snow-cut along the roadway. Facing hazardous conditions each spring became expected procedure for park crews, and since the local economic interest in the road opening increased throughout the 1950s, allowing a natural snowmelt was an impossible consideration. Local demands called for skilled crews, better equipment, and the expenditure of more Park Service funds. Mel Ruder also suggested that in light of the hazard, "another possibility to consider is snow sheds over the Sun highway in certain slide areas." Since snowsheds would lessen the danger but impair the scenic drive, the proposal never received serious consideration. Instead, road crewmen began to carry small devices which transmitted signals, not to reduce the danger, but to enable search teams to locate them readily should their burial occur. |

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

Man in Glacier ©1976, Glacier Natural History Association buchholtz/chap6.htm — 28-Feb-2006 Copyright © 1976 Glacier Natural History Association. All rights reserved. Material from this edition may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and publisher. | ||